Being a successful leader in the age of automation comes down to a simple mantra

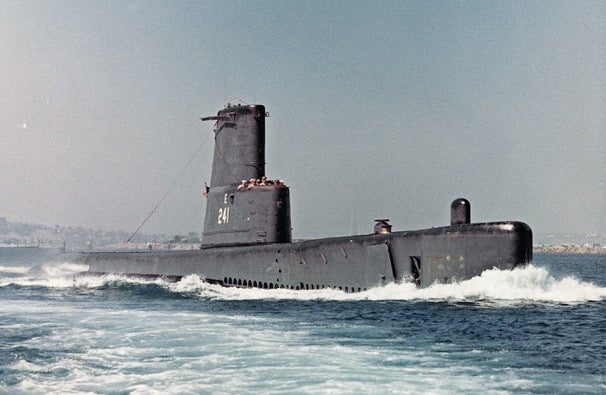

In 1960, American career submarine officer Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard—son of famed hot-air balloonist and scientist Auguste Piccard—were the first two people to reach the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans. How deep is deep? If you placed all 29,000 feet of Mount Everest on the bottom of the trench, it would still be 1.2 miles underwater.

In 1960, American career submarine officer Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard—son of famed hot-air balloonist and scientist Auguste Piccard—were the first two people to reach the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans. How deep is deep? If you placed all 29,000 feet of Mount Everest on the bottom of the trench, it would still be 1.2 miles underwater.

When I met Walsh at the Global Exploration Summit in Lisbon, a meeting of the intrepid members of The Explorers Club, I asked him for advice that had proven helpful to him during his career. His four-word answer is an instruction for leaders both above ground and below water:

“Manage machines, lead people.”

During his many years in the US Navy both before and after the Mariana Trench expedition, Walsh went through a lot of leadership training. This was back in the late 1950s, when manpower—emphasis on man, as women were not permitted to serve aboard submarines until 2010—was the primary resource the military had at its disposal. That said, the submarine force had long been using emerging technologies for both battle and research, and training its sailors to use these newfangled inventions.

The way that Walsh learned to deal with the tension between man and machine was to focus on the emotional, human qualities of the crew he was leading, and leave the automatic thinking for the machines they manned. Rather than trying to control the changing technology itself, he focused his leadership efforts on the happiness of the operators.

“Having nice shiny kit is fine, but if the people operating it are not motivated, then you will not do well,” Walsh says. “Motivated men are to marvelous machines as 10 is to one.”

Keeping your crew in high spirits while at the depths of the ocean could be a particularly trying task: No sunlight, no access to the outside world, sometimes for as long as two months at a time. Nope, just your fellow seamen and some fish to keep you company. Instead of big, showy displays of camaraderie, Walsh opted for smaller, more intimate daily check-ins. “It was important to have day-to-day conversations to make sure that everyone’s happy,” he says. “I would take their pulse with respect to how morale goes. ‘Are things at home okay?’ for example. They were not used to being away from their families for long periods of time. You’ve got to be sensitive to that.”

Fast forward six decades, and in many ways, the machines are now managing us. Depending on whose analysis you choose, 40% of us will be automated out of our jobs in the next 15 years, or we may have job security for a lot longer than the naysayers believe. If we are part of the lucky cohort who keep on the same career track, our roles will still likely integrate more and more technology.

In Walsh’s day, it was too cumbersome to use a machine to do a human’s job. “It was cheaper to put a man in those machines, because we didn’t have the electronics and battery systems and magic stuff we have today—everything was too big,” he says. “But you put a person in there, and a pretty reliable computer, and you get the job done.”

Back then, a big reason people were put into submersibles was that the necessary equipment couldn’t be made small enough and still “equal the ‘computing power’ of the on-board human,” Walsh says. Nowadays, we can fit entire libraries on thumb drives and entire digital worlds in our pockets.

But when we start leading machines instead of people, what else do we lose?

“I’m not going against my own trade, but I do think that robotics are the future,” he says. “But what kid wants to grow up and be a robot?”