How to deal with an abusive boss

More than a decade has passed, but Mary Mawritz can still hear metal-tipped tassels flapping against leather loafers—the signature sound of her boss roaming the halls of his real estate company. “Whenever I heard that jingling, I would get sick to my stomach because I knew he was approaching,” she says. Her boss had another characteristic sound: Yelling, and a lot of it. He would berate her in front of the whole office and threaten to fire her immediately if she didn’t keep up with his never-ending barrage of deadlines and demands.

More than a decade has passed, but Mary Mawritz can still hear metal-tipped tassels flapping against leather loafers—the signature sound of her boss roaming the halls of his real estate company. “Whenever I heard that jingling, I would get sick to my stomach because I knew he was approaching,” she says. Her boss had another characteristic sound: Yelling, and a lot of it. He would berate her in front of the whole office and threaten to fire her immediately if she didn’t keep up with his never-ending barrage of deadlines and demands.

Mawritz would go home at night with a splitting headache and a lot of questions: Why did he act like that? Why did he think it was OK to treat people that way? Lots of workers have asked themselves similar questions, but Mawritz has made a career of it. Now a business management researcher at Drexel University’s LeBow College of Business in Philadelphia, she’s one of many experts who are using insights from psychology and business management to tackle the phenomenon of bad bosses, a stubbornly persistent problem that continues to drive people out of promising careers, hurt companies’ bottom lines, and ruin a lot of otherwise decent days.

Through interviews, surveys and on-the-job observations, scholars are building their case against toxic bosses and putting the worst offenders on notice. They say that if more companies knew how to prevent breakdowns in leadership, if more bosses realized that yelling and bullying aren’t ways to get ahead, and if more employees knew how to deal with the jerks above them, workplaces everywhere would be saner and more productive places and fewer people would get sick at the sound of shoes.

The abuse checklist

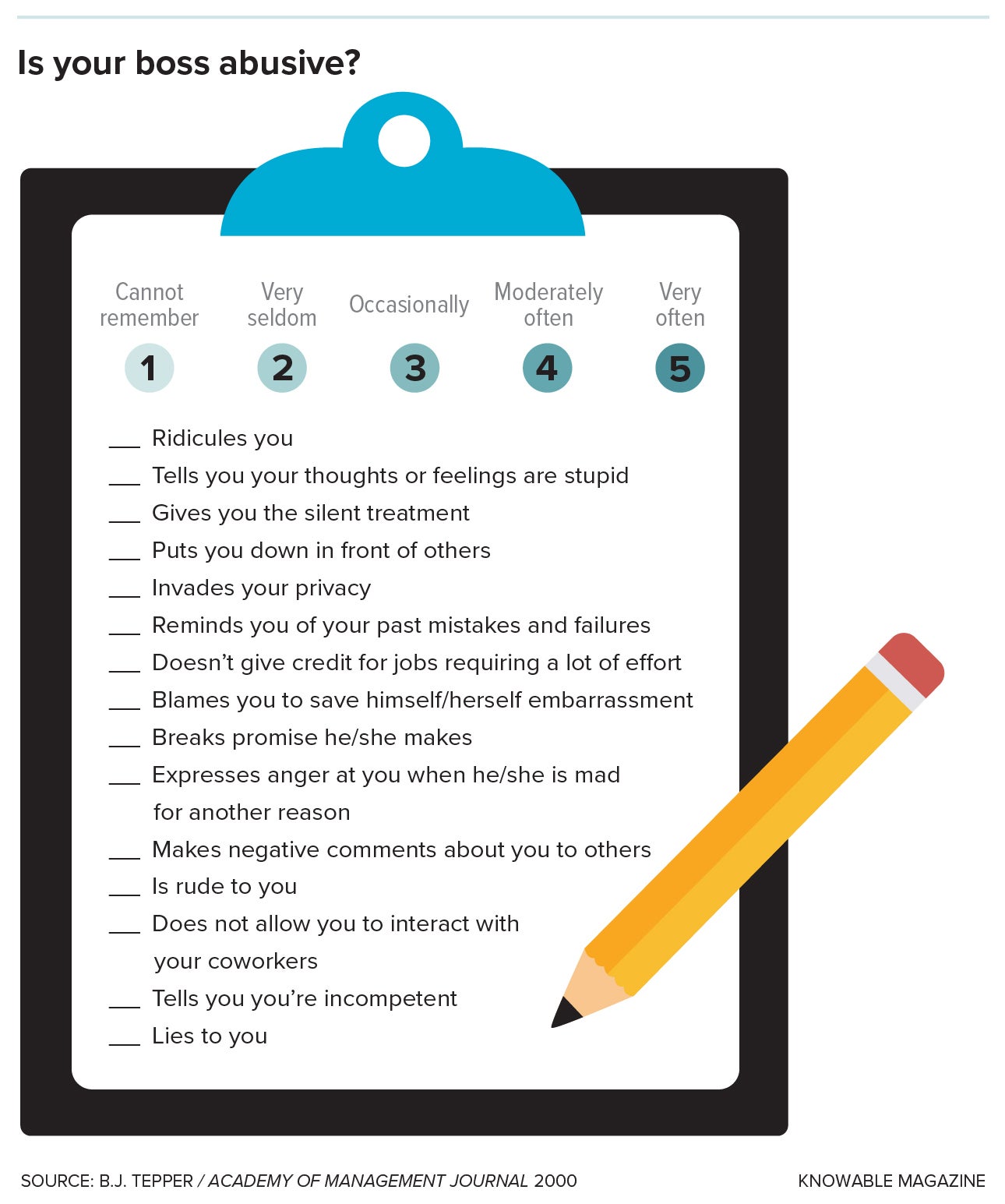

Bad bosses have likely been around since our hunting and gathering days—back when a “PowerPoint presentation” meant getting jabbed with a spear—but the science of supervisors-gone-bad is surprisingly new. Bennett Tepper, a management and human resources researcher at Fisher College of Business at Ohio State University in Columbus, coined the term abusive supervision in 2000, more than a decade after the debut of Dilbert. Complaints about bosses may be age-old, but Tepper helped formalize the field by developing a 15-point checklist of bad-boss behavior, including “tells me my thoughts or feelings are stupid,” “tells me I’m incompetent,” and “lies to me.”

For nearly two decades, Tepper and others have used that checklist to gauge the experiences of employees in a wide variety of jobs, including sales, tech, education and health care. If an employee agrees strongly or very strongly with three or more items on the list, a boss is considered abusive. The good news is that truly toxic bosses are far outnumbered by the common run-of-the-mill bunglers and bumblers that just about everyone has encountered at some point in their work life. Only about 10% of bosses cross the line from merely overbearing to abusive, Tepper says, and that number has stayed remarkably steady from workplace to workplace and from year to year. Pick a boss at random from any industry, and there’s a one-in-ten chance that you’ve found someone with a knack for making employees miserable.

Tepper says there’s one big exception to the one-in-ten rule, a place where abusive bosses are about three times more common than in the rest of society. It’s not Wall Street or Hollywood, but the college locker rooms, stadiums and fields of America. According to studies by the NCAA, the major governing body of collegiate sports in the US, more than one-third of all college coaches in football, women’s softball, and other sports have embraced the abusive approach. “There’s a belief that hostility gets results,” Tepper says.

The record books show that Bobby Knight—the frequently angry, foulmouthed, chair-throwing former basketball coach of the Indiana Hoosiers—did win three national championships. But could he have achieved such success (or even more) without the tantrums? Tepper points to mounting research suggesting that abusive bossing brings out the worst in employees. For example, a 2007 study in 265 chain restaurants in the US found that restaurants with abusive managers lose more food from waste and theft. More alarmingly, a 2013 Journal of Applied Psychology study of more than 2,500 US soldiers who were on active duty in Iraq found that service members with emotionally abusive officers were more likely to admit hitting and kicking innocent civilians and were less likely to report misdeeds by others. By every account, leaders and managers who bully and berate their employees don’t make any more sales, reap more profits, win more games, or move up the corporate ladder faster than leaders who take a more gentle approach. “Things never get better as abuse increases,” Tepper says. “They always get worse.”

Still, too many bosses—including some who wouldn’t themselves fit the “abusive” definition—deeply believe the myth that bullying works. The vision of a rough, tough, effective boss is deeply entrenched in the American workforce, says Robert Sutton, a business researcher at Stanford University and author of The Asshole Survival Guide: How to Deal with People Who Treat You Like Dirt (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017). As he delivers his “No Asshole” message around the country, he finds lots of people who seem baffled by the very suggestion that they don’t need to curse and yell to get ahead. “I gave a talk to a bunch of National Football League executives, and they didn’t get it at all,” he says. “It was the least successful ‘asshole’ talk I ever gave.”

With bullying, both sides lose

Despite the persistent mythology, there are no winners when bosses turn abusive, Mawritz says. The bosses themselves gain nothing of value, and their behavior leaves a lasting mark on employees. “Everyone remembers that one person in their professional life who engaged in those behaviors,” she says. “Their physical and psychological reactions were incredibly strong.”

“People often quit their bosses, not their jobs. People who are the highest performers have the most options. You can lose your best people that way.”

—Frederick Morgeson

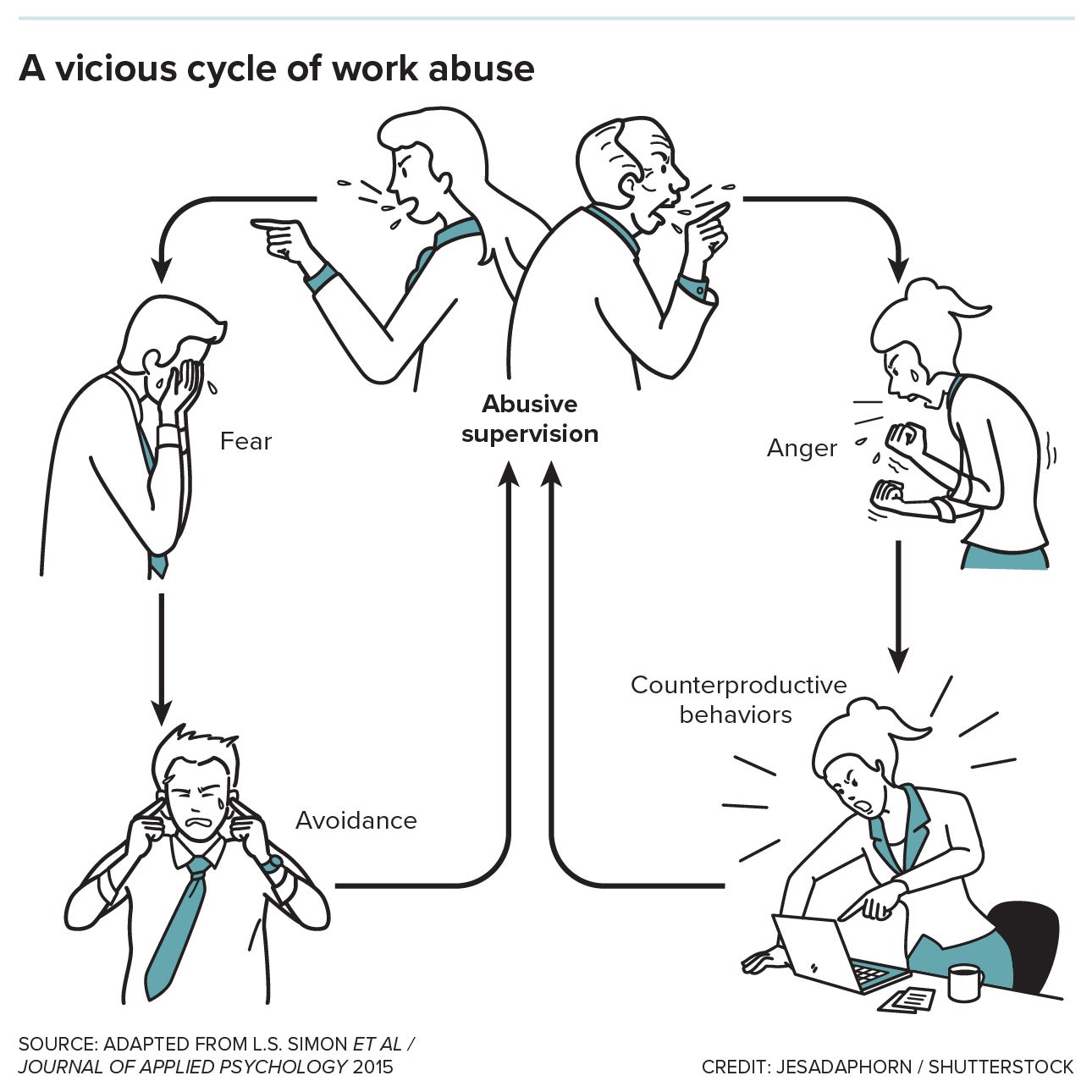

The consequences spread far beyond the heat of the moment. Tepper has found from surveys that employees with abusive bosses tend to be less satisfied with their jobs—no surprise. But they were also less satisfied with their lives as a whole, and they had more conflicts at work and home. Writing in the Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior in 2017, Tepper noted that people with bullying bosses tend to report being more withdrawn and depressed in these surveys. He writes that “targets of abusive supervision report symptomatology that bears striking similarities to those diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.”

As much as some bosses may seem to relish a chance to berate their employees, bullying isn’t rewarding for them either, Sutton says. On a professional level, they end up with a team that’s too demoralized and de-energized to do their best work. Personally, all of that bluster and rage can wear a person down. Sutton points to a new paper in the Academy of Management Journal that used multiple email surveys sent throughout the day to track the moods and attitudes of bosses. The study found that bosses who were abusive at work struggled to relax and generally felt unfulfilled when off the clock. “People who bully other people at work suffer themselves,” he says.

How to handle an abusive manager

Bad bosses can show up in any industry, says Stanford business researcher Robert Sutton. Here’s his advice for employees trying to cope with a toxic leader.

- Consider jumping ship. Sutton says he’s a big proponent of quitting a toxic boss whenever possible. Only about 10% of bosses fit the abusive profile, so you’re likely to do better next time. But if your next boss and your boss after that aren’t upgrades, you might need to look inward. “If everywhere you go people are treating you like dirt, you might be triggering them, or you might have thin skin,” Sutton says.

- Team up. Sutton has often seen employees work together to create an “asshole detection system” to gauge a boss’s mood. If the system is red-lining, everyone can lie low and wait for another day to ask for help or deliver bad news. “The sophistication of some of these efforts is amazing,” he says. “It becomes a big part of their job.”

- Keep your distance. Simply reducing contact with a bad boss can do wonders for your work-day and your mental health. Sutton recommends being slow to respond to emails, cutting back on face-to-face meetings, and generally keeping a safe distance. “It’s like the boss is kryptonite,” he says.

- Take the long view. Many employees get through the day by reminding themselves that even the worst moments will pass. “You can convince yourself that even if someone is treating you like dirt, it won’t mean anything a year from now,” he says.

- Don’t fan the flames. If your boss is looking for a target, don’t put a bullseye on your back. Sutton urges employees to avoid being boisterous or overly aggressive. (In nature and in offices, staying inconspicuous is a proven survival strategy.) Also, don’t openly disparage management or talk about bosses behind their backs, and don’t do anything to undermine their authority. Bad bosses may be a scourge, but a truly dysfunctional workplace is almost always a group effort.

Such conflict can harm companies, too, says Frederick Morgeson, a business and management expert at Michigan State University in East Lansing. Abusive bosses, he says, can drive talented employees right out of the office. “People often quit their bosses, not their jobs,” he says. “People who are the highest performers have the most options. You can lose your best people that way.”

With so many losers on all sides, it may seem puzzling that office managers and CEOs around the world come to work ready to fight, or allow abuse to go on under their watch. Companies could do great things for their employees and their own bottom line by keeping abusive bosses out of the workplace, but first they have to figure out where they come from. And that’s where Tepper and others have important news: Jerks, for the most part, aren’t born that way. They’re created.

Good old-fashioned jerks

So what turns a boss bad? Sometimes they just don’t know any better. “It’s an old-school way of thinking,” Mawritz says. “Some leaders walk around thinking that their employees are lazy, incompetent, and dumb. They have a mentality that they have to act a certain way to get people to do what they want them to do.” This belief, that bullying works, has been passed down to the next generation. Tepper teaches classes full of MBA students about the hazards of abusive management, and their attitude says a lot about today’s business culture. “If I give them a case where a boss is hostile but seems to have a good job performance, they think he’s a hero,” he says.

Even if bosses don’t buy into this hero narrative, the nature of some jobs can push them across the line, Tepper says. Even the most mild-mannered do-gooder can turn nasty given enough pressure and aggravation. Likewise, Tepper says, under favorable conditions, a real virtuoso of yelling can go through their entire work life without ever feeling the need to be mean.

Over the years, Tepper and others have identified some of the most important on-the-job triggers that can turn potentially decent bosses into jerks. Pressure to perform is one. If a boss is really feeling the heat from above, the people beneath can get burned, or at least a little singed. Bosses are also more likely to be abusive if there’s a huge power gap between leaders and employees, Tepper says. Pressure and power gaps are firmly baked into the system, so there’s not much hope for major change. “As long as those factors are in the crucible, you’re going to have some abusive behavior,” he says.

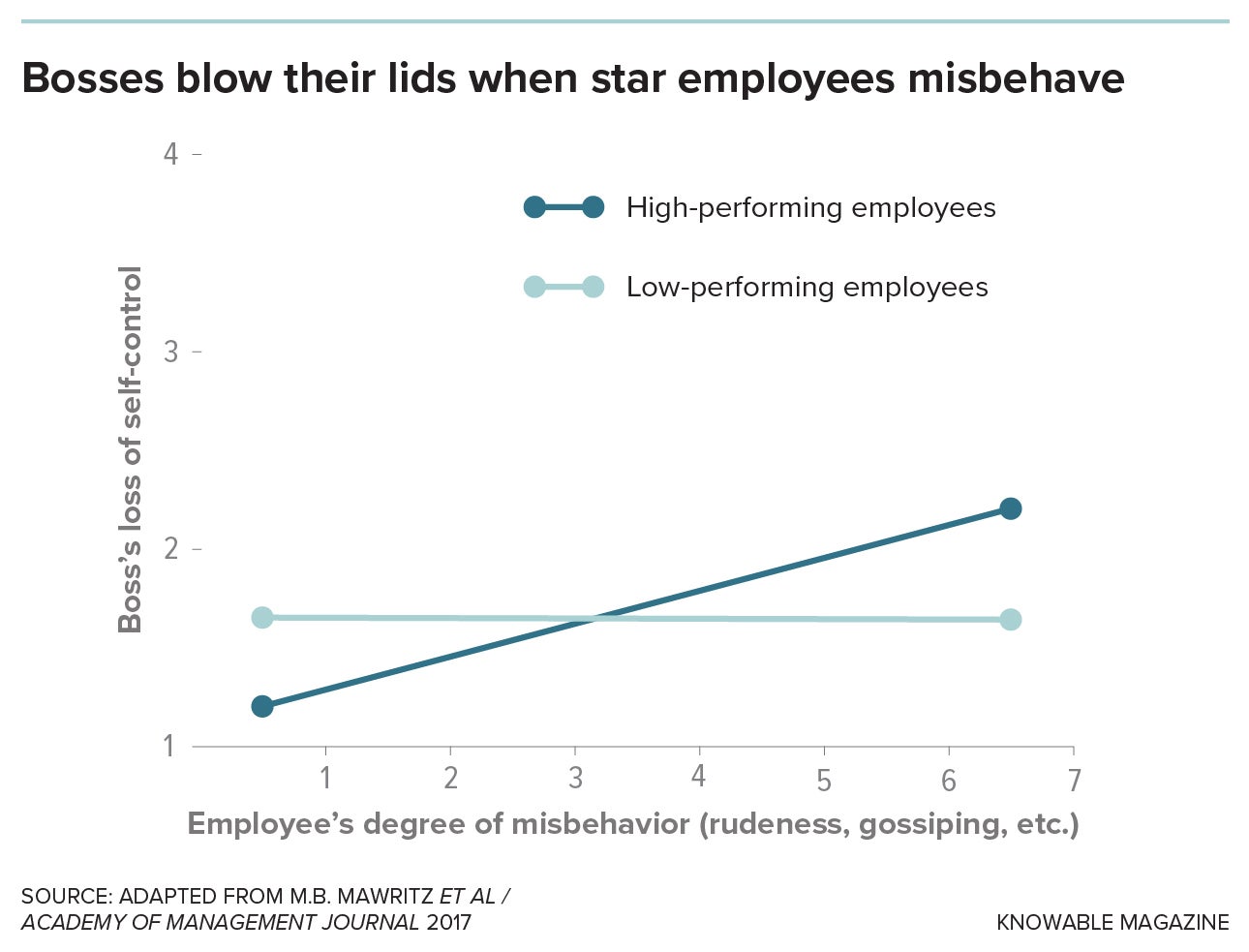

But there’s another, less-understood and far more controversial trigger for bad bosses. Time and again, Mawritz says, the trouble largely starts not with the bosses but with the employees. She says she doesn’t want to “blame the victim,” and she doesn’t want to let abusive bosses completely off the hook. But research over the years paints a clear picture: Through their attitudes and actions, employees have a lot of power to send a boss over the edge. Tepper agrees that many employees inadvertently encourage abusive behavior. “Hostile bosses aren’t hostile with everybody,” he says. “They pick and choose their targets.”

Don’t contribute to the problem

Suffice it to say, there are right ways and wrong ways to handle a boss. In a 2017 study that combined extensive surveys of 165 pairs of supervisors and employees, Mawritz and colleagues found that bosses can lose control and become abusive if they feel that employees have turned against them. Gossiping about supervisors definitely invited trouble, and being rude only fueled bosses’ bad tempers. “They get frustrated and annoyed, and they fly off the handle,” Mawritz says. To her surprise, the study found that bosses were particularly likely to lose their cool with stellar, high-performing employees who showed signs of disrespect. “I thought the high performers would be sheltered,” she says. That finding made her reminisce about her own days at that real estate company. She says she wasn’t much of a gossip, and happened to be one of the more productive employees in the company—which earned her zero protection when those tassels started jingling in the hallway.

Somewhat depressingly, there’s one tried-and-true method for staying on the good side of a boss. “If you want to get ahead, you have to kiss up,” Sutton says. Long before the invention of the assembly line or the cubicle, employees have been flattering their managers and laughing insincerely at bad jokes, and the approach hasn’t lost effectiveness with time. Bosses often claim they want to surround themselves with people who will “give it to them straight” and “tell it like it is,” Sutton says, but they really like the employees who say nice things and deliver good news.

The right way to deal with bad bosses

Change comes slowly. Some companies are actually trying to take a stand against the kiss-up culture, Sutton says. He recently gave a talk at Netflix, and he says the company actively encourages employees to speak up, even when they don’t have great things to say. “That’s really very unusual,” he says, and “very impressive.”

The attitude at Netflix is just one example of a new approach that’s seeping into the corporate mindset. Sutton says that even companies with a dark history of toxic bosses are now trying to address the issue. Simple awareness is an important first step. Sutton travels the world driving home the point that being abusive doesn’t bring an upside for a boss or the company. As he puts it, successful assholes are successful despite being assholes, not because of it.

Other companies are trying to improve leadership by taking a closer look at how they promote people. In many cases, Morgeson says, employees become bosses because they were really good at their previous jobs, even if those jobs didn’t involve any management duties. He’s seen the pattern again and again: An excellent nurse or doctor becomes a hospital administrator, a top-notch car engineer gets bumped up to head of engineering. (Some call it the Peter Principle: People will rise through a business until they reach a level of incompetence.) Too often, they have trouble letting go of their previous position, so they become stressed-out micromanagers. The inevitable frustration with a position they’re unprepared for, untrained for, and may not show much aptitude for, can boil over into hostility and abuse.

Companies can break that cycle by providing management training and promoting people based on their actual ability to do the new job, not their other skills or, even worse, their connections. As Morgeson says, politics can poison a company. Promotions become an exercise in favoritism, and bosses pick on the powerless. But breaking cycles takes effort, and not every company is willing to try. “I find it interesting how organizations respond to this,” Morgeson says. “Some get on top of the issue, and some decide not to do anything, for whatever reason.”

In the end, bad bosses are likely to persist in the workplace, Mawritz says: “Maybe I’m taking a cynical view, but people are often not willing to change.” Perhaps no research study or seminar could have saved her from the abuse and headaches that came with her real estate job—she ultimately saved herself and her sanity by walking out the door and never going back. A bad boss can keep employees down, but most of them do manage to move on. Like Mawritz, they escape with their dignity and more than a few good stories that will never get old.

Just ask her about those tassels.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.