The new US labor secretary has a history of opposing workers’ rights

The new US secretary of labor has a lot of experience dealing with workers’ rights. Mostly, he’s fought against them.

The new US secretary of labor has a lot of experience dealing with workers’ rights. Mostly, he’s fought against them.

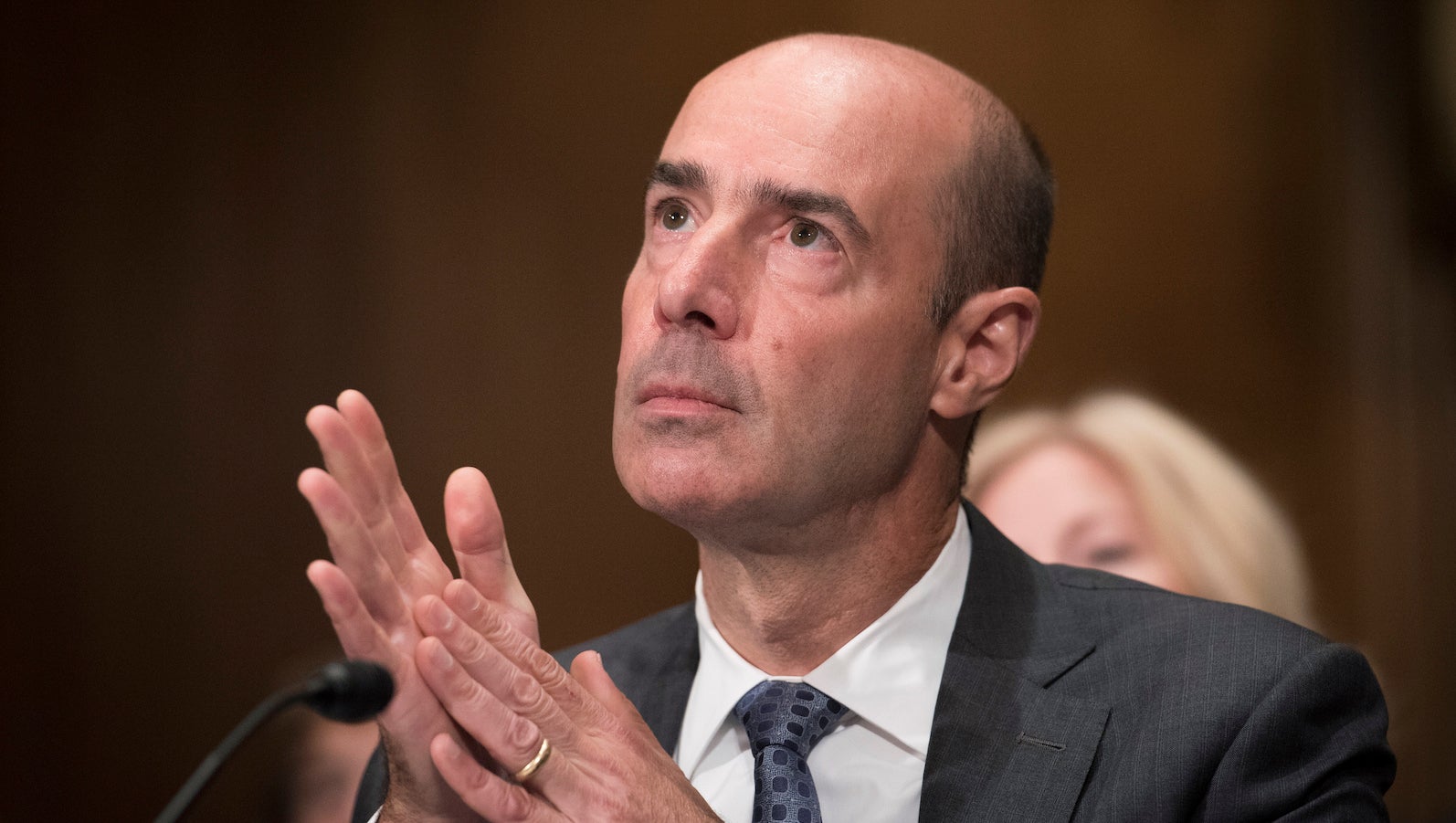

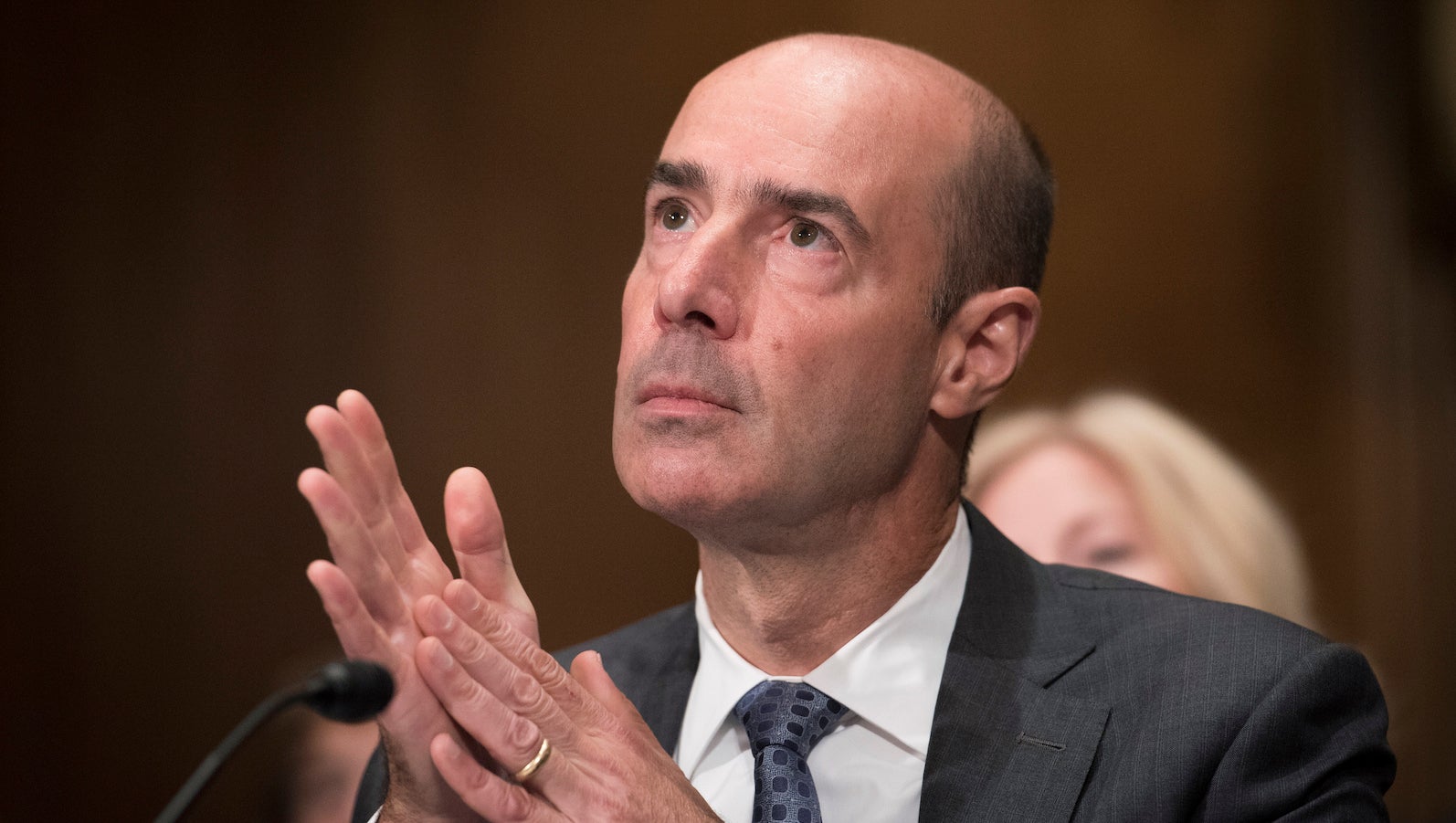

Eugene Scalia, who was confirmed today by a Senate vote of 53 to 44, is a partner at the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher specializing in labor and employment issues, and the son of the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia. In July, Donald Trump announced Scalia as his pick to replace Alexander Acosta, who resigned from the post that month over his handling of a plea deal given to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Senate Democrats opposed Scalia’s nomination because of the lawyer’s history defending clients like Walmart and UPS in cases involving issues such as employee healthcare and accommodations for workers with disabilities. “President Trump has again chosen someone who has proven to put corporate interests over those of worker rights,” New York senator Charles Schumer told the New York Times. “Workers and union members who believed candidate Trump when he campaigned as pro-worker should feel betrayed.” Senator Patty Murray of Washington said in a July statement that she opposed Scalia’s nomination “because of his hostility towards workplace protections and his positions on workplace harassment and workers’ health and safety.”

That said, Scalia did work as the Labor Department’s solicitor under George W. Bush before returning to private practice. And perhaps surprisingly, officials who worked with Scalia there said that he was committed to defending workers’ rights over that period. One of his former subordinates told the Times that while she was “appalled when he was nominated to the position…she was pleasantly surprised to find him reasonable and relatively committed to protecting workers.” And Bloomberg reported that a group of former Labor Department lawyers signed a letter supporting Scalia’s nomination as secretary of labor, saying that they’d found him to be “very supportive of enforcement litigation to vindicate the rights of workers, both at the trial and appellate levels.”

So what are we to make of Scalia? Here are a few key points from his past that may help the public better understand the controversy over the man who will head a department sworn to “foster, promote, and develop the welfare of the wage earners, job seekers, and retirees of the United States.”

Defeating a law to provide healthcare for Walmart workers

In 2006, Maryland passed the Fair Share Act, which would have required Walmart to spend 8% of its payroll on health insurance for workers or else contribute the difference to the state’s Medicaid fund. Representing Walmart, Scalia succeeded in striking down the law; a Maryland appeals court ruled that it violated the federal labor law called Erisa, which had been created to give national companies the ability to provide uniform healthcare for all of their workers across the country rather than address each state’s laws.

Nixing the Obama-era fiduciary rule

In 2016, the Labor Department passed a fiduciary or “conflict of interest” rule that required brokers giving advice on retirement accounts to put their clients’ best interests ahead of their own financial gain from commissions. Working on behalf of nine trade groups, including the US Chamber of Commerce and the Financial Services Roundtable, Scalia helped defeat the law, which he called (pdf) “one of the broadest, most aggressive regulatory maneuvers I’ve ever seen by an agency.”

Defending UPS against workers with disabilities

In one case, as summarized in a 2009 court ruling, Scalia advocated for UPS against employees who’d suffered injuries on the job. The workers claimed that UPS denied them accommodation when they attempted to come back to work with certain medical restrictions, “effectively precluding them from resuming employment at UPS in any capacity because of their impaired condition.”

The UPS employees asked to be certified as a class so they could bring their claims against the company as a group, but in 2009, an appeals court ruled in favor of Scalia and his team, who had argued that assessing whether all plaintiffs qualified for protection under the Americans with Disabilities Act “would entail too many individualized inquiries for class treatment to be warranted.”

Repealing protections against on-the-job injuries

In one of Scalia’s most well-known cases, he attacked the scientific premise that workers could suffer injuries from performing repetitive tasks while working to appeal a Clinton-era ergonomics rule meant to protect workers from hurting themselves. “Ergonomists are not physicians—they are engineers—and their medical theories are controversial,” he wrote in 2000 (pdf). “Some of the world’s leading medical researchers deny that repetitive motion causes injury.”

The rule, which the Occupational Safety and Health Administration said would prevent 460,000 musculoskeletal injuries on the job per year, was overturned under Bush, who said it would have “cost both large and small employers billions of dollars and presented employers with overwhelming compliance challenges.”

It’s worth noting that Scalia changed his tune when he was nominated for the solicitor job at the Labor Department in 2001, saying, “I’ve taken pains to acknowledge that ergonomic pain is real and that ergonomics is valid.”

Arguing that a worker with IBS should wear diapers to work

Writing at Talk Poverty, Taryn Williams explains a case in which Scalia represented Ford Motor Company:

In the Ford case, Scalia defended the company against a claim that it had failed to accommodate a person with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The plaintiff had requested telework as a reasonable accommodation, which the company refused and countered with an offer to move the employee’s cubicle closer to the restroom.

When the plaintiff explained that simply standing up could trigger a loss of bowel control, Scalia argued (pdf) that they should have taken “self-help steps such as using Depends (a product specifically designed for incontinence) and bringing a change of clothes to the workplace.” In other words, when an employee asked for support, Scalia argued that she should wear a diaper and be ready to change her pants.

Ford won the case, though a dissenting judge argued (pdf), “it is unreasonable to respond that Harris could wear Depends or clean herself up after any accidents. Harris should not have to suffer the embarrassment of regularly soiling herself in front of her coworkers.”

What Scalia says

When questioned by senators ahead of the confirmation vote about his history when it comes to workers’ rights, Scalia suggested that he was simply doing his job to defend corporate clients. “That doesn’t mean that I think what they did was proper or I agree with them,” he said, suggesting he would operate differently while serving the Labor Department.

“I did handle some cases for clients, it was my job at my firm and I had a duty actually to do that vigorously as a lawyer,” he told senators last week. “When I was at the Labor Department before, I was ever mindful that I had a new set of responsibilities and even a higher set of responsibilities. The most important thing to me as a practitioner has been fidelity to my obligations and to the law.”

Even if Scalia is able to separate himself from the positions he’s taken in the past, Democratic senator Chris Murphy questioned whether someone who has actively worked against workers’ rights is the best person to defend them.

“I have plenty of friends who work for big companies and work in employment law and many of them are fine people,” Murphy said, “but I don’t know that I would select them to be the one representative in the federal government, in the cabinet who is supposed to speak for workers.”

This story has been updated to reflect that the Senate confirmed Scalia as labor secretary on Sept. 26.