Your productivity hacks are useless without this one essential theory

The first-ever productivity tool was likely something like a simple to-do list, with tasks written down in order of importance. Today, that simple tool has morphed into a seemingly endless vortex of complex software tools, scheduling systems, and applications.

The first-ever productivity tool was likely something like a simple to-do list, with tasks written down in order of importance. Today, that simple tool has morphed into a seemingly endless vortex of complex software tools, scheduling systems, and applications.

Thanks to the suite of productivity-enhancing options now available to us—from online organization tools to flexible work-from-home policies to tech gadgets—we are more attuned than ever to our own individual productivity. Our obsession with productiveness has spawned an entire industry.

But even with the increased focus on productivity as a skill in itself, it can be challenging in today’s modern workplace for organizations and leaders to find the time and space to step back and assess employee productivity at scale.

The question for organizations today is: Does our enhanced awareness of productivity actually drive meaningful results in work output—or is it mostly just noise?

People before programs

First things first: No matter what your organizational system is, the largest differentiating factor in human productivity is the actual person who uses it.

A person’s inherent skill set, ability to prioritize, switch between tasks, and coordinate among teams are the strongest indicators of the ability to execute tasks efficiently and strategically.

From an employer’s perspective, this may seem like an ambiguous and difficult group of skills to assess. From an employee’s perspective, this may seem like a lofty and ambitious set of skills to monitor and master.

At my organization, Meseekna, we study critical lens-questions like this every day; questions that require us to zoom in to focus on a person’s daily decision-making and then zoom back out to grasp the impact those decisions have on the larger organization. In order to do this, we focus on metacognition: what I like to call the “how” of thinking, rather than the “what.” By viewing productivity through the prism of metacognition, we can break down a complex concept into three identifiable parts—task orientation, activity level, and task management. By doing this, we make human productivity much easier to both assess and improve.

Often, the ability to prioritize has much more to it than merely looking at your list of daily tasks. We view it as the ability to strategically gauge which projects and tasks benefit the individual and the organization the most, as well as their relative probability of success—and importantly, the magnitude of that success.

Orient yourself

In order to make smart choices in the workplace context, both employers and employees should focus their efforts on tasks that have the greatest relevance to the organization, and with which they believe they have a strong likelihood of success, personally.

This is something we reference frequently as task orientation. In employees, it often surfaces as a willingness to identify the most important tasks that need to be done and to do them well for the benefit of the team.

When thinking about your own productivity, moments that are characterized by high task orientation feel driven and purposeful. The larger vision is in clear sight, and you can feel yourself moving along a path toward it.

Activate your purpose

I find it helpful to differentiate between activity for the sake of activity (what we often refer to as “busy work”) and activity with a purpose, as overall activity versus focused and applied activity.

People who are usually considered to be great employees spend the bulk of their time in focused, applied activity. They are fully aware of their own goals, the company mission, and can plot their own strategic path to merge the two together. When assessing your own productivity, these moments of focused activity are easily identifiable as moments of “flow” or being “in the zone.”

Manage and delegate

The last key aspect to productivity is often the most difficult to master: task management. As employees move up the corporate ladder, their success is often defined by their ability to delegate tasks to other employees that may prove challenging, too time consuming, or outside of their skill range.

There’s a common perception that people who are skilled at task management rapidly out-produce their peers. But in reality it mostly comes down to a matter of being able to identify who is best suited to perform a specific type of task.

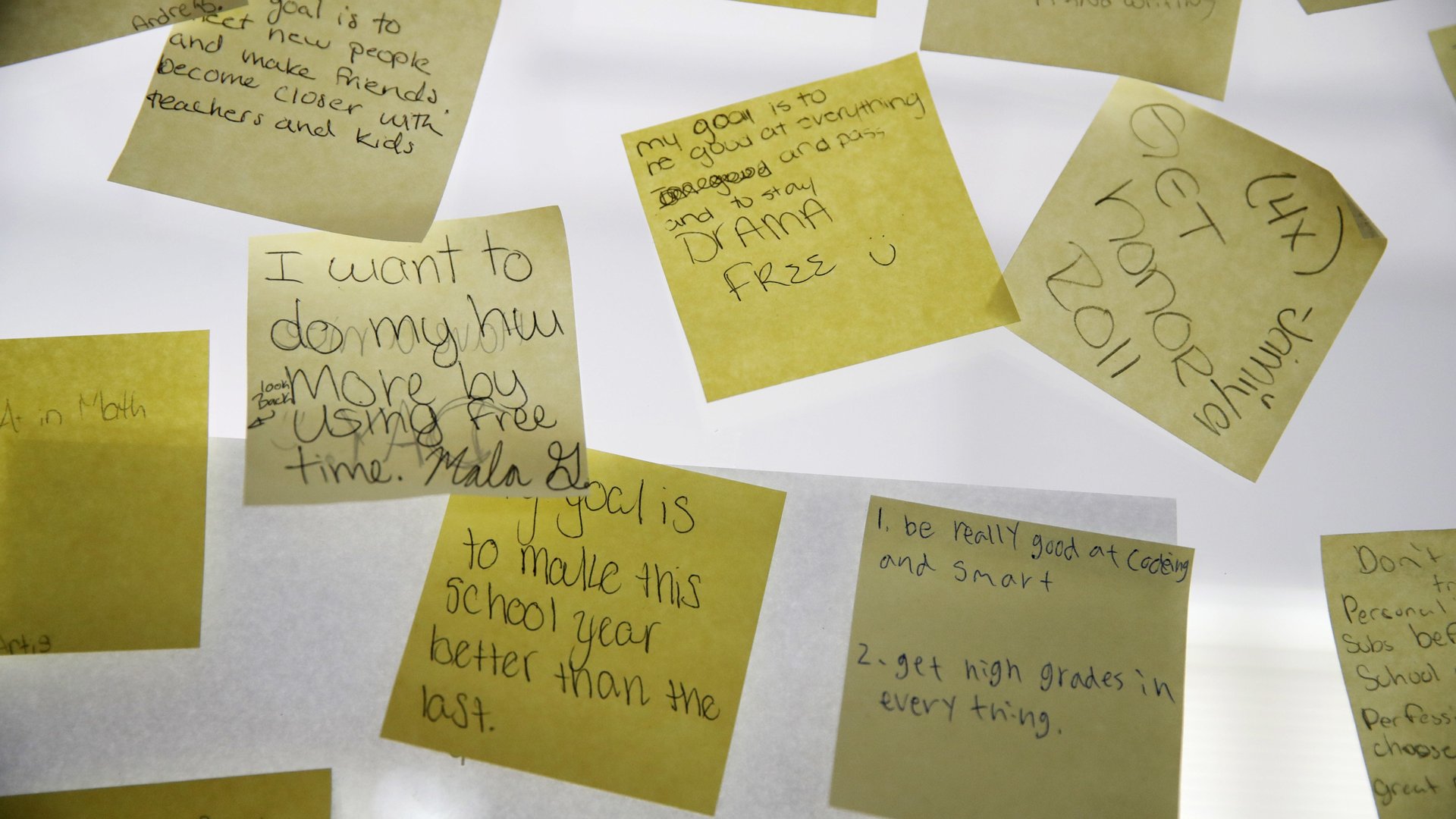

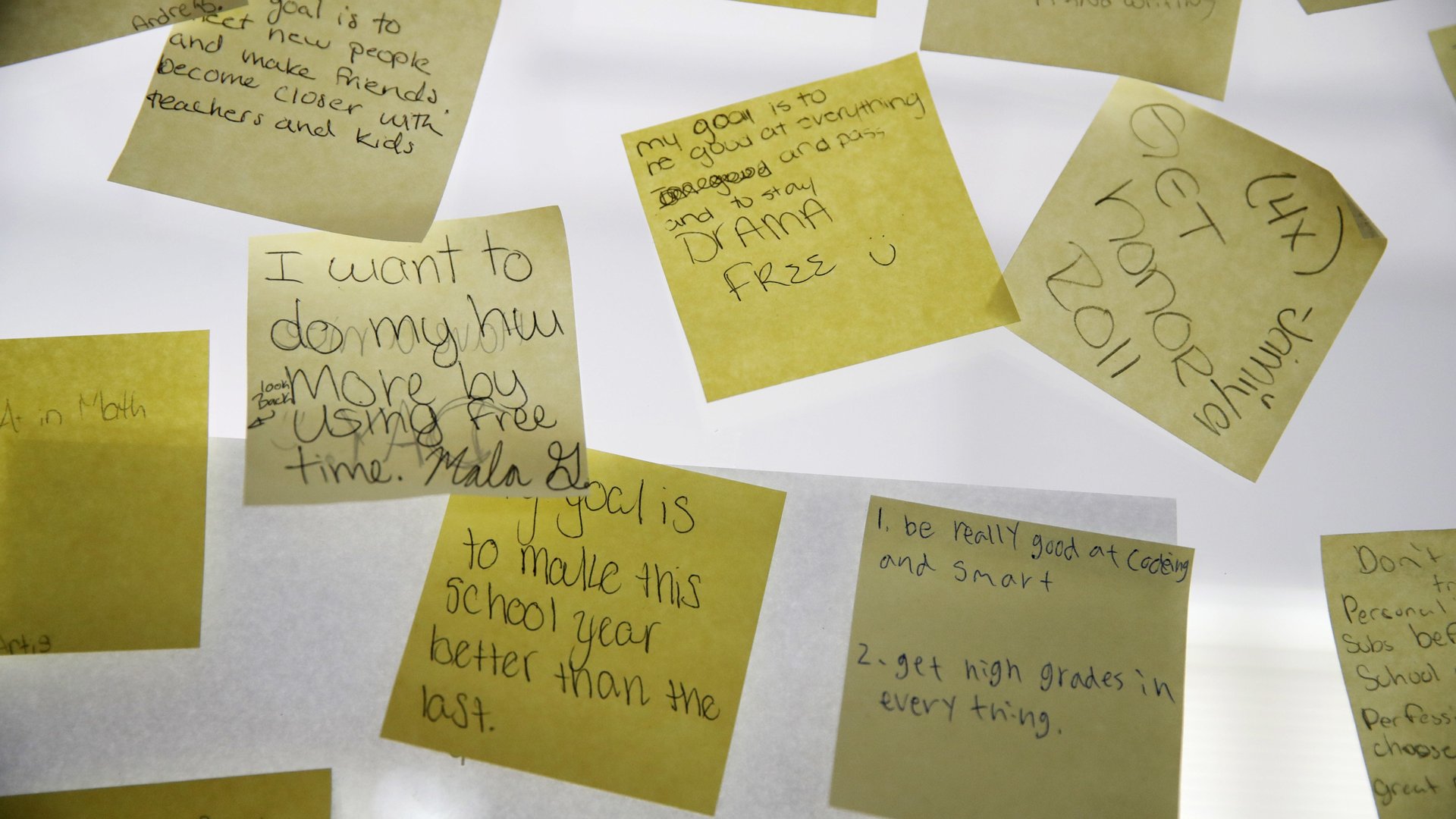

A metacognitive understanding of productivity can help not only in professional life, but in personal growth and wellbeing as well. In reflecting on your own task management, habits like keeping a log of daily tasks and noting down where you struggled, where you felt most comfortable, and where you felt the most challenged can be helpful. It can allow you to identify your own patterns, which lets you see both your successes and areas that need work.

Employees and organizations should have a shared goal of maximizing productivity without sacrificing time or causing frustration. This simple metacognitive framework can help you think critically about our own processes, and learn how to truly make a difference.