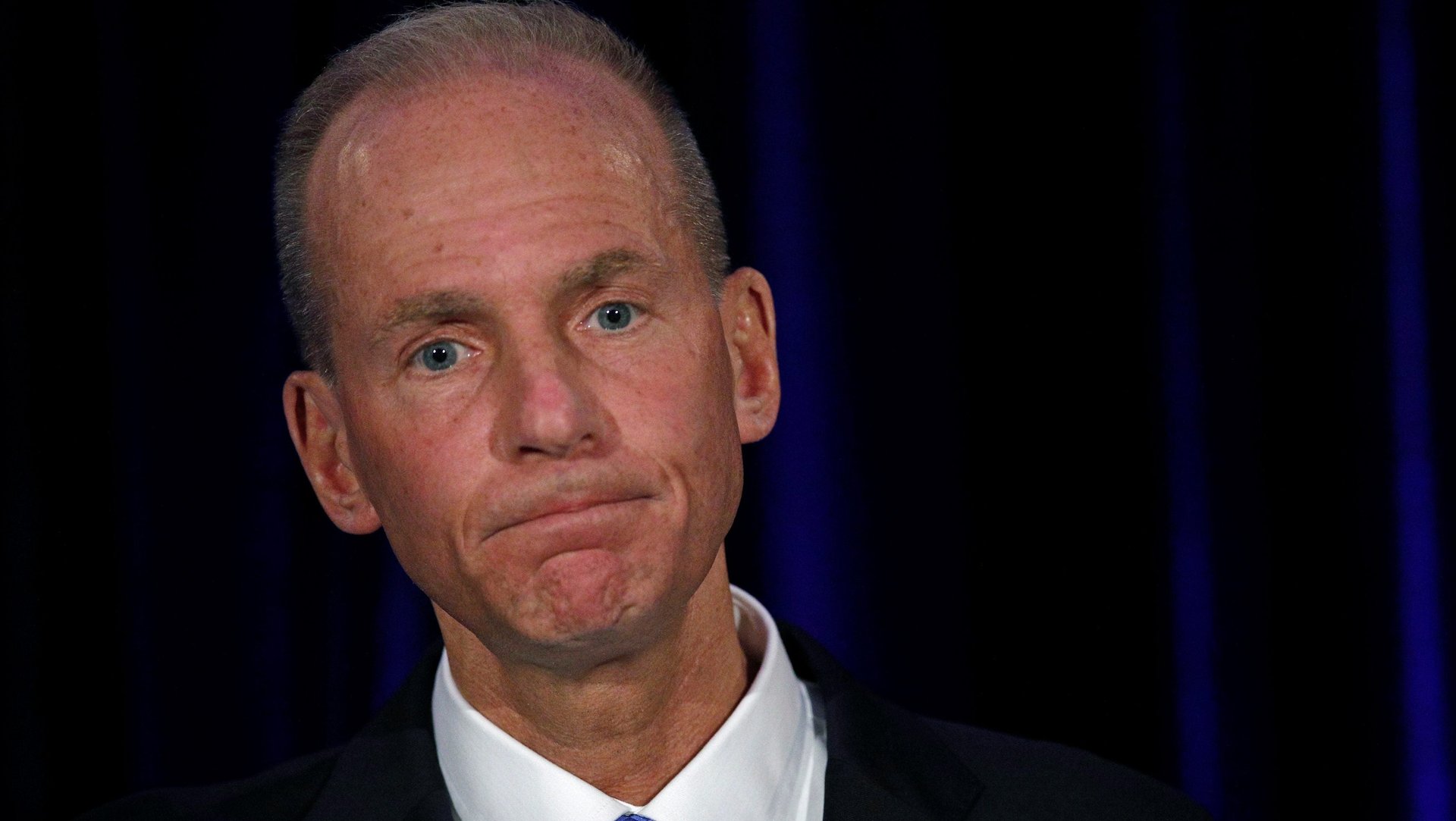

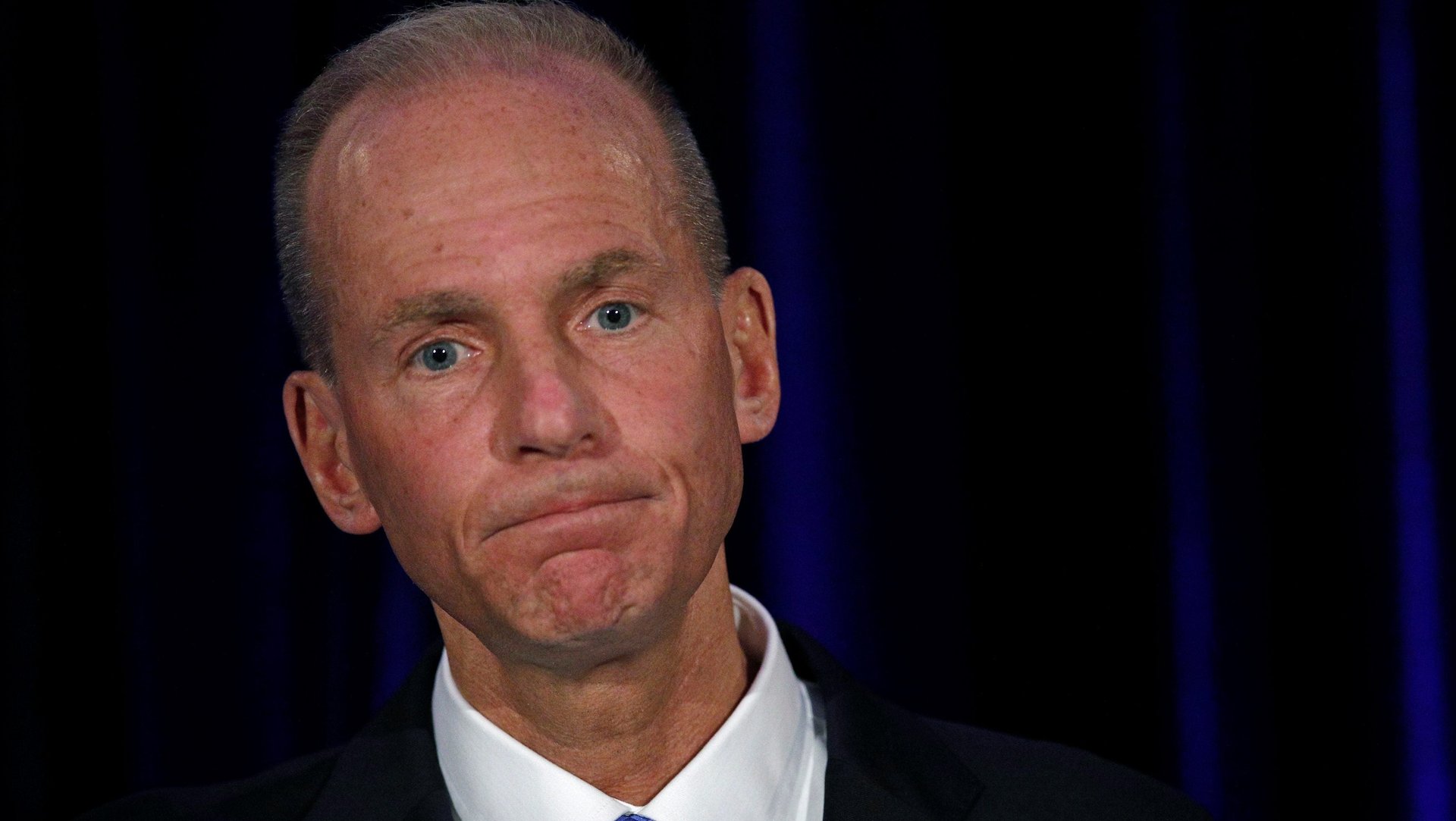

What do Boeing CEO’s Dennis Muilenburg’s apologies actually mean?

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg likely thought he was done with the day’s apologies.

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg likely thought he was done with the day’s apologies.

But as he turned to leave a congressional hearing on Oct. 29, the executive was asked for yet another—this time, from the mother of one of the 157 victims killed in the March 2019 Ethiopian Air crash, aboard a Boeing 737 Max 8 jet.

“Mr. Muilenburg, turn and look at people when you say you’re sorry,” Nadia Milleron said to the executive, according to a tweet from New York Times reporter Natalie Kitroeff. Muilenburg duly turned, looked her “in the eye,” and replied: “I’m sorry.”

Muilenburg has spent a lot of time this year saying sorry, in formats ranging from video releases to newspaper advertisements and congressional testimonies. But despite the volume of the apologies, there’s a key problem with them: As Boeing is concerned, the crashes still aren’t its fault.

The company earlier this week took out full-page ads in Indonesia’s Jakarta Post and the Wall Street Journal, in which it professed to be “deeply sorry” and promised to “always remember” the victims of the two 737 max crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia. At the start of the congressional hearing, Muilenburg addressed family members of the more than 300 people killed:

“I’d like to speak directly to the families of the victims who are here with us. On behalf of myself and the Boeing company, we’re sorry. Deeply and truly sorry. As a husband and father myself, I’m heartbroken by your losses. I think about you and your loved ones every day, and I know our entire Boeing team does as well. I know that probably doesn’t offer much comfort and healing at this point, but I want you to know that we carry those memories with us every day, and every day that drives us to improve the safety of our airplanes and our industry. That will never stop.”

The company’s initial apologies were rather less heartfelt. Initially after the Ethiopian Air crash, the plane manufacturer issued a boilerplate non-apology in a press release on its website, which expressed sadness—just about—but did not take responsibility for the crashes: “Boeing is deeply saddened to learn of the passing of the passengers and crew on Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, a 737 MAX 8 airplane. We extend our heartfelt sympathies to the families and loved ones of the passengers and crew on board and stand ready to support the Ethiopian Airlines team.”

By April, the tone had changed—a little. In a video release, Muilenberg gave a fuller apology: “We at Boeing are sorry for the lives lost in the recent 737 MAX accidents.” But in an earnings call later that month, he alluded to the possibility of pilot error in causing the crashes, calling them “a series of events, and that is very common to all accidents that we’ve seen in history.” Throughout it all, Muilenburg maintained there had not been any “technical slip” that could be blamed on Boeing.

Over time, as more information about the crashes seemed to suggest wrongdoing on Boeing’s part, the apologies have grown more elaborate. Speaking to CBS, Muilenberg doubled down: “I do personally apologize to the families, as I’ve mentioned earlier we feel terrible about these accidents, and we apologize for what happened, we are sorry for the loss of lives in both accidents,” he said, citing the impacts on families and loved ones. “I can tell you it affects me directly as a leader of this company, it’s very difficult.” (Later on, in discussing the impacts on airline customers, he said the company was “taking responsibility” and was “committed to safety for the long run.”)

But if Boeing isn’t at fault, as it maintains, what, if anything, do these apologies mean? And what’s the point of making them?

The power of saying sorry

In 1982, seven Chicagoans died after an unknown person—perhaps a disgruntled Johnson & Johnson employee—laced bottles of Tylenol, the company’s bestselling product, with cyanide. The company responded immediately, issuing an apology and recalling around 31 million bottles of the product—often cited as a gold standard of crisis management. It paid off: In the long run, the deaths had little impact on the company’s share price, while Tylenol retained its market share.

Apologies work. In his book Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation, the sociologist Nicolas Tavuchis describes how an apology, if accepted, allows life to go on “as if nothing had happened.” We might remember what took place, but “for all practical purposes, the social slate is wiped clean,” in an emotional exchange at once commonplace, taken for granted “and yet so mysterious.” In a management context, as crisis management researcher Keith Michael Hearit writes, the apology serves as a kind of public confessional, which “completes the story” and allows everyone to move on.

More than that, an apology can sometimes be the least expensive way of resolving a crisis. Studies suggest apologizing can be as effective, and often cheaper, as offering compensation in improving how customers perceive a company. (Boeing has done that too—though at about $145,000 per victim, it’s less than it might have been obliged to offer in a legal settlement.)

Saying sorry can actually help avoid a lawsuit altogether: More than 35 states across the US have laws in place that allow doctors to apologize for “adverse medical events” without the fear of it being used as evidence in court.

In a paper in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, authors Benjamin Ho and Elaine Liu lay out the two premises for these laws. First, they suggest, doctors often want to apologize, but feel hamstrung by the fear of potential lawsuits. When they don’t apologize, however, patients get annoyed, often triggering a desire to sue and leading to a “vicious cycle” that results in high litigation costs. All this anger, Ho and Liu write, “might have been assuaged by an apology.”

When doctors apologize, without being understood as taking legal responsibility, Ho and Liu found, claims are settled faster, more cheaply, and with less litigation. Here, the law presumes that patients will understand the apology as “a signal that the bad outcome arose from bad luck rather than a lack of effort.”

In saying sorry, Boeing is hoping to be read in much the same way as these doctors: Even though it does not believe that the crashes were its fault, it is sad nonetheless, and would have preferred them not to have happened. (The company will certainly have sought legal advice before saying sorry.) Even though Boeing hasn’t acknowledged significant wrongful action on its part, it still regrets what took place. The hope is, like the patients or the Tylenol consumers, prospective customers will see the company in a better light, and their anger will be reduced.

An apology in two parts

Weeks after the Ethiopian Air crash, a Bloomberg editorial by opinion columnist Brooke Sutherland accused the plane manufacturer’s apology tour of lacking an apology: “After initially being caught in an isolated defense of the Max’s airworthiness as regulators around the globe grounded the plane, Boeing and the FAA are attempting to steer the conversation away from what went wrong with promises to do better in the future.”

To really deliver a genuine apology, according to a 2008 paper by philosopher Luc Bovens, it must be made in “a humble manner”—first, bowing one’s head in shame “for serious wrongdoings;” second, making up for the “deficit of respect” with which someone else has been treated; finally, “relinquishing power” to whomever has been hurt to “restore moral stature.” The person, or people, apologized to, must believe that the apologizer would have behaved differently, given the opportunity.

Right now, Boeing’s apologies appear to be more focused on rebuilding the relationship with customers than on actually fixing the problem or offering an explanation. It’s not surprising if they thus ring a little hollow—especially since the company’s attempts to fix the problem appear to be being done at the behest of the FAA, rather than its own leadership.

For customers to accept Boeing’s apology, and put their trust in the company, they must have faith it really wants to change. Muilenburg’s “sorries,” no matter how many of them there are, may not go far enough to convince them.