Have a strong accent? Here’s how that hurts your paycheck

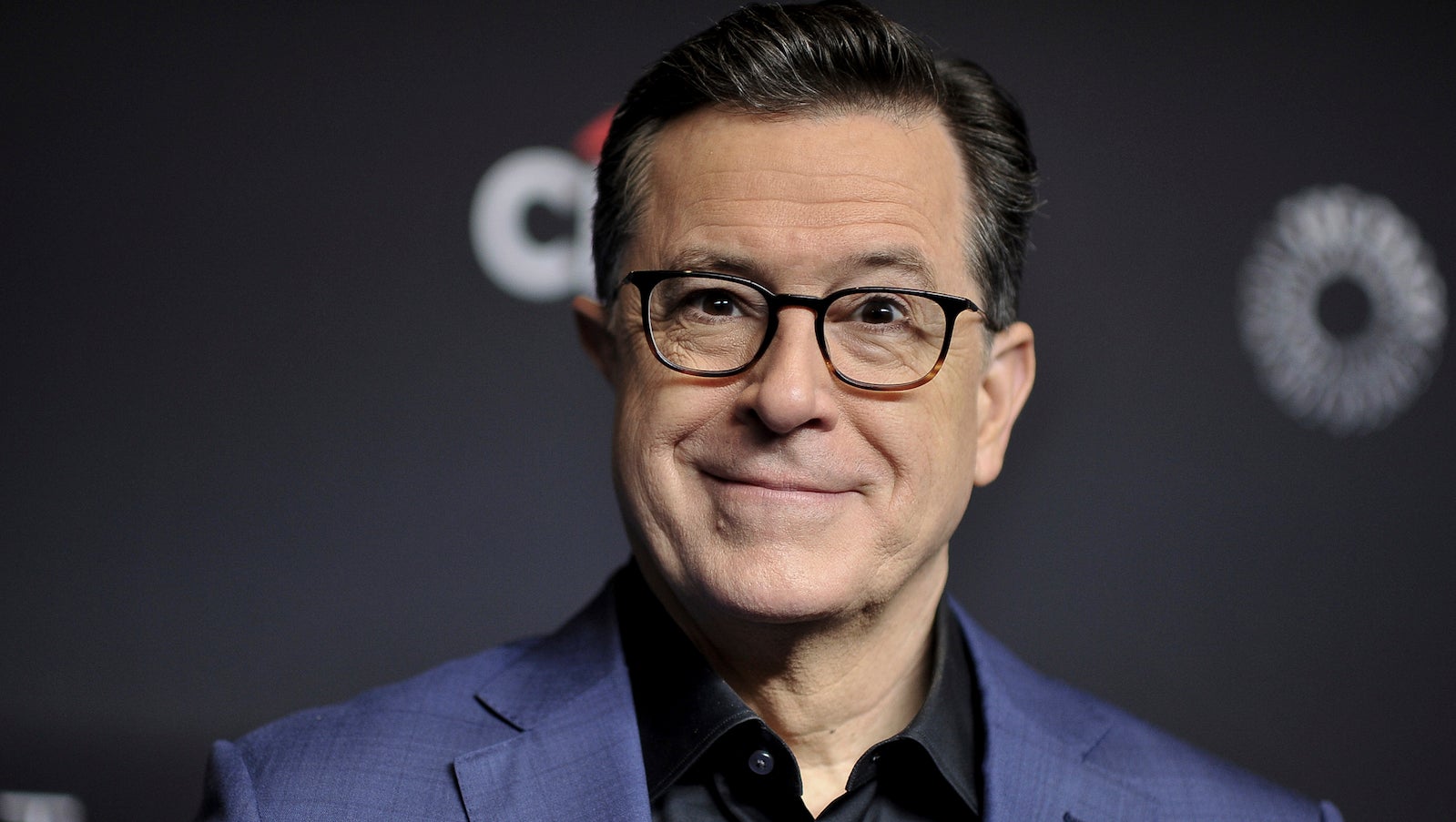

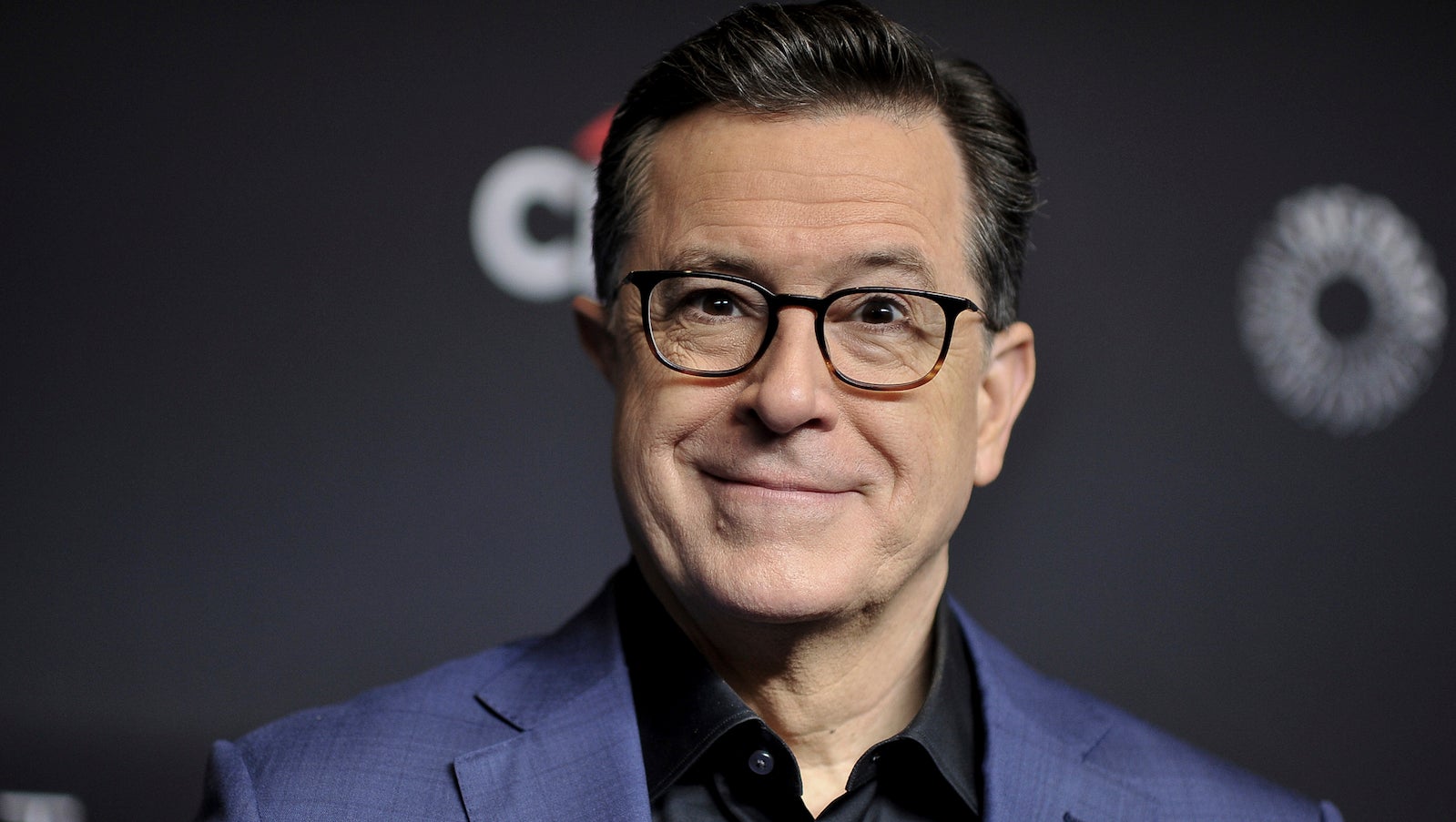

Stephen Colbert grew up in South Carolina, but he doesn’t have a Southern accent. That’s because, even as a child, the comedian and TV host knew that other people might hold a distinctive drawl against him.

Stephen Colbert grew up in South Carolina, but he doesn’t have a Southern accent. That’s because, even as a child, the comedian and TV host knew that other people might hold a distinctive drawl against him.

“At a very young age, I decided I was not gonna have a Southern accent,” Colbert said in a 2006 interview with 60 Minutes. “When I was a kid watching TV, if you wanted to use a shorthand that someone was stupid, you gave the character a Southern accent. And that’s not true. Southern people are not stupid. But I didn’t wanna seem stupid. I wanted to seem smart.”

It’s decidedly unfair that Colbert felt pressured to change the way he spoke in order to avoid negative stereotypes. But biases against certain regional accents are common around the world. In the UK, the working-class Birmingham (or “Brummie”) accent is famously scorned. In Japan, the Tōhoku regional accent is stereotypically associated with laziness and provinciality; in Brazil, Northeastern accents are considered socially inferior.

A new paper aims to pin down the cost of such bias in the workplace. People with strong regional accents face a wage penalty of 20% compared to those who speak a standard accent, according to a new working paper by researchers at the University of Chicago and the University of Munich. That’s a penalty on par with the gender wage gap.

The study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was posted on the National Bureau of Economic Research website. It drew on a nationally representative sample of 950 people in Germany.

The study’s authors say that Germany was an ideal setting for their inquiry because different regions of the country are each associated with different accents. In other words, “it is not as if one part of the country speaks standard German while another part speaks with a regional dialect.” The fact that regional accents are associated with both high-income and low-income parts of Germany reduced the risk that the correlations between wage patterns and accents could be attributed to a given region’s socioeconomic status.

So why is there a link between strong regional accents and lower wages? The answer has more to do with stigma than with accents themselves. “The employer has to charge consumers a lower price, or pay coworkers a higher wage, to induce them to interact with an employee against whom they are prejudiced,” the authors write. “The result is a lower wage for workers with a stigmatized trait, such as a regional accent.” Another variation on that explanation could be that because workers with strong accents encounter more bias from their colleagues and customers, it’s harder for them to do their jobs effectively.

In both scenarios, workers with stronger accents seek out jobs that involve less interpersonal interaction, which often pay less. Sure enough, the researchers found that Germans with stronger accents seemed to hold less social occupations.

The study is in keeping with other research on how accents impact people’s livelihoods. One of its authors, University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger, published a paper in the Journal of Human Resources in 2018 focused on speech patterns in the US. He found that black Americans who spoke with a “mainstream” dialect tended to earn more money than those who spoke African-American Vernacular English (AAVE). Again, this is the result of prejudice. Speakers of AAVE may find themselves shut out from jobs that involve higher levels of interaction with colleagues, clients, and customers, which often pay more (as is the case with management jobs, for example).

Research also shows that people with certain foreign accents are also at a higher risk of employment discrimination. In one high-profile example of such bias, venture capitalist Paul Graham, the cofounder of startup accelerator Y Combinator, got into hot water back in 2013 after telling Inc. magazine that he was wary of entrepreneurs with heavy foreign accents. “Anyone with half a brain would realize you’re going to be more successful if you speak idiomatic English, so they must just be clueless if they haven’t gotten rid of their strong accent,” he said.

Combatting negative stereotypes about people with regional, racial, and foreign accents is necessary to put workers on a more level playing field. But as long as bias persists, it’s no surprise that people like Colbert may conclude that they need to change the way they speak in order to succeed—or else move to a place where a given accent doesn’t have the same stigma.

The latter choice was the one pursued by Fiona Hill, the UK-born Russia expert and former official at the National Security Council who testified during Donald Trump’s impeachment trial. Hill noted in her opening statement that she had moved to the US to avoid classist reactions to her speech. “I grew up poor with a very distinctive working-class accent,” she said. “In England in the 1980s and 1990s, this would have impeded my professional advancement. This background has never set me back in America.” The US, of course, is hardly free of biases—but it does lack that particular one.