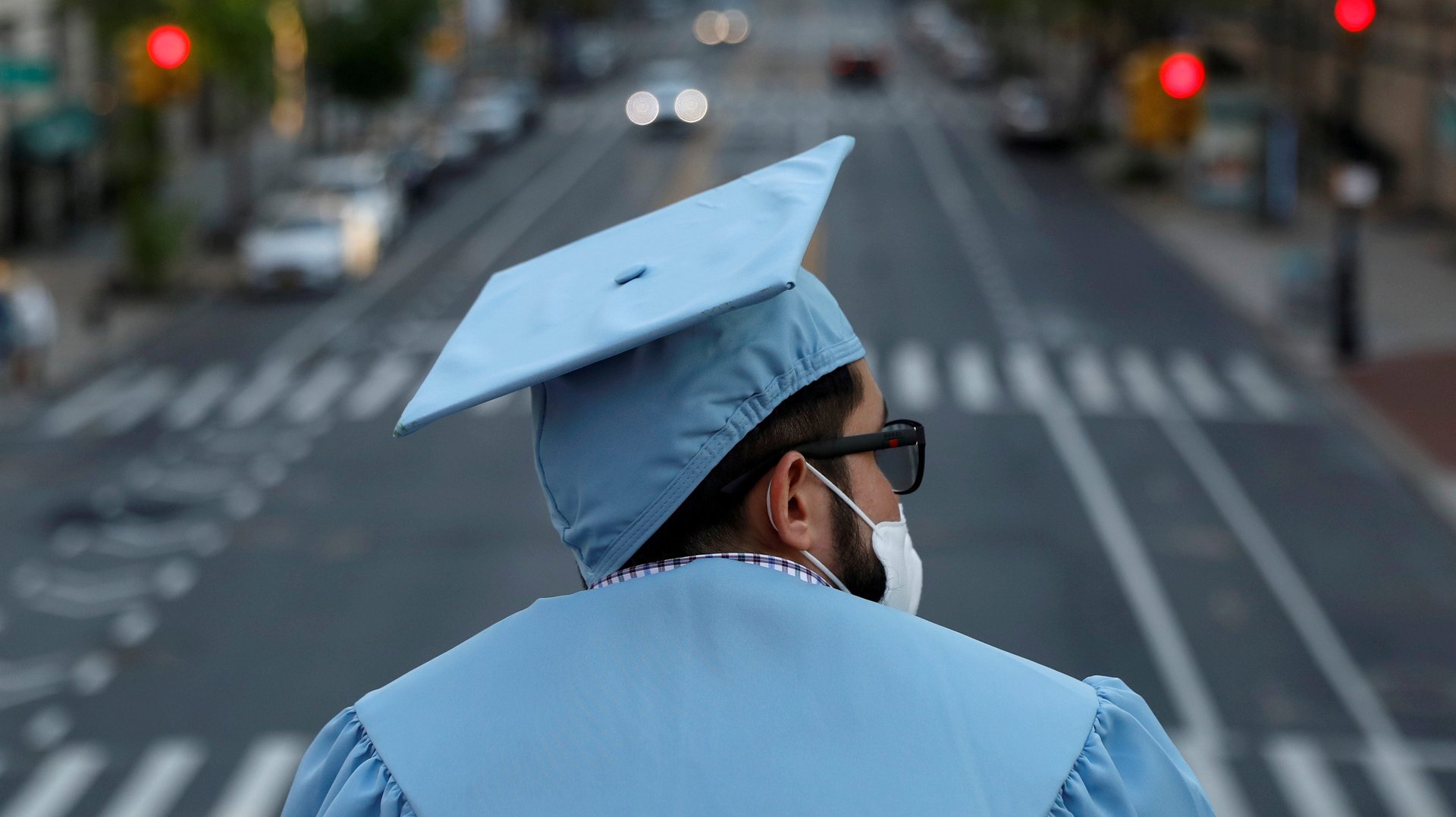

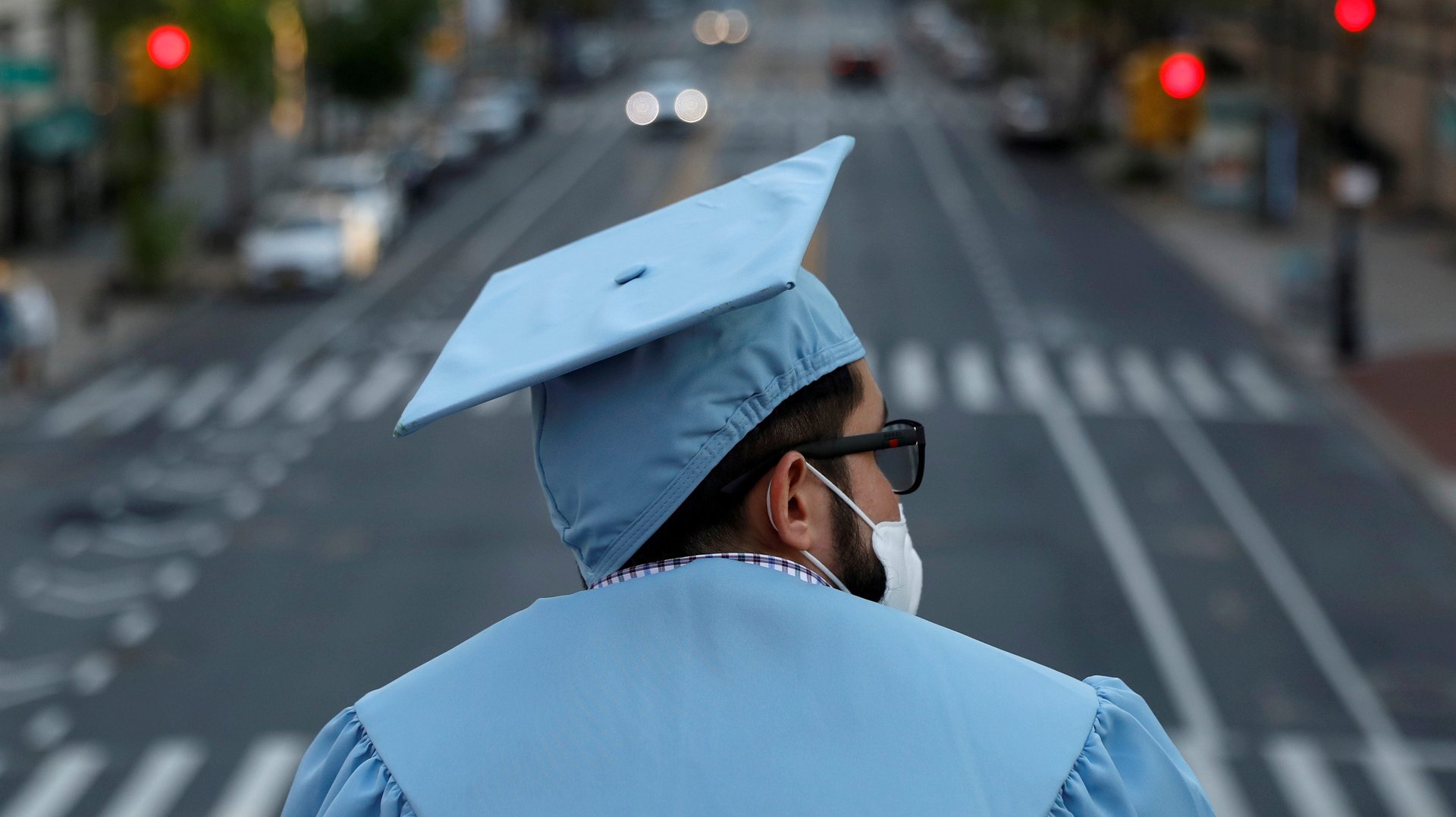

We are all in the class of Covid-19, graduation TBD

Before I earned my doctorate in clinical psychology, I was, for one night, a prep cook and dishwasher in San Francisco’s Mission District. I knew I had no business being in that kitchen; I was a fraud. But I had recently been freed from the cushy constraints of college and had no direction. The diploma handed to me months earlier was a meaningless rubber stamp on an inconsistent, uninspired undergraduate performance. I had no idea how to prove my mettle outside of the ivory tower, and thought frequently of my father, who taught junior high in the South Bronx all day and then worked a maitre d’ shift at the Carnegie Deli at night.

Before I earned my doctorate in clinical psychology, I was, for one night, a prep cook and dishwasher in San Francisco’s Mission District. I knew I had no business being in that kitchen; I was a fraud. But I had recently been freed from the cushy constraints of college and had no direction. The diploma handed to me months earlier was a meaningless rubber stamp on an inconsistent, uninspired undergraduate performance. I had no idea how to prove my mettle outside of the ivory tower, and thought frequently of my father, who taught junior high in the South Bronx all day and then worked a maitre d’ shift at the Carnegie Deli at night.

My feelings of self doubt and purposelessness—the desperation to prove myself—affected me so profoundly that I would write my dissertation on post-college transitions, and have paid close attention to the themes of emerging adulthood in my clinical work. But the challenges I faced 25 years ago pale in comparison to the cataclysmic terrain the class of 2020 must now traverse as they finish school and attempt to get started in life.

It’s glaringly clear that the class of 2020 is going to need a little extra love, care, and attention. What’s less obvious is that we are all looking at the world through the eyes of a recent college graduate at this moment. But I’ve been doing around 45 remote sessions a week with my patients since social-distancing and sheltering-in-place have become the norm, and I’ve learned that we are all in the class of Covid-19, graduation TBD.

An abrupt dislocation and uncertain future

The challenges that define the post-college transition are the same challenges that define what I have dubbed “the Covid-19 transformation.”

Leaving college can be experienced as an abrupt dislocation, and what follows can feel monotonous and undifferentiated—all the more so for our current cohort of college seniors, who have been brusquely, unceremoniously evacuated back into their childhood homes to spend every waking hour with a familiar cast of characters, with no breaks or end in sight. They are back in a life they thought they had outgrown, with their frustration and premature stagnation essentially on steroids, while the people they thought would be comforting them through this crisis and leading the way forward are in a confusing collective pause themselves.

Many of us conceptualize and experience our lives as a goal-oriented, accomplishment-driven journey of progressive ascension, with clear markers of success and rewards of periodic leisure. What recent grads must learn, what my artist patients learn early, and what we all must relearn during this time, is how to positively orient ourselves according to our internal compasses, even when what comes next is not clear and we do not know what we can expect from others, nor what others expect of us.

The increased uncertainty and isolation of post-graduate life evokes a natural impulse to reach out, while the need to demonstrate maturity and self-reliance makes these impulses intolerable. “I hate you, don’t leave me” (or end this Zoom meeting). Some recent grads feel pressure to abruptly let go of, or awkwardly hold onto, relationships that have become suddenly distant. Now, along with the rest of us, their ambivalence is heightened and complicated by quarantining and mandated social-distancing.

Having succeeded in establishing some degree of confidence and know-how, recent grads are coming home to a far less familiar world than the one they left. Both the return home and the absence of the familiar social order can have a regressive effect, causing recent grads to feel helpless, ineffective, and frustratingly dependent. There is a good chance the established, competent adults paying the bills are struggling to maintain a facade of control themselves and questioning what self-reliance looks like these days. We are all trying to figure out what we need and who we can rely on for what. We are all in a state of heightened dependence and craving comfort, companionship, guidance, and certainty while knowing how important it is to develop and demonstrate our independence and personal grit.

Strong leadership at home (and in the workplace and in politics) during this time is transparent. It seeks to create tolerance of, and comfort in, not knowing. This is not a time for cowards, but we should all be on the lookout for false prophets and tough-guy posturing. Anyone who comes away from surveying the current landscape asserting “I got this,” should be regarded with suspicion.

Making room to listen and reflect

One of the most daunting facets of leaving the comforts of college is the shift in scale. College is a curated, secure, well-appointed and maintained pool, with a full bar. This year’s seniors have been told, “Pool’s closed, we will send your diploma in the mail.” They are instead being thrust into the ocean, and peering longingly to shore, only to see the beach is closed due to Covid-19.

Rather than feeling ready to scale the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, raising their hands in victory like Rocky and heading in to day one of their real, adult life, many recent grads will instead ascend the stairs of their childhood home to submit resumes into the ether of the post-Covid-19 economic depression. Sadly Mom, Dad, and Aunt Linda are applying to the same gigs, with their still-unpaid-for master’s degrees, while simultaneously learning about unemployment benefits and mortgage forbearance.

The drudgery of wading through the swampy, unglamorous terrain of emerging adulthood can feel vaguely worth it, if it allows you to have your ticket punched into the Real World. But Covid-19 canceled reality for the foreseeable future. There are no more kids, teens, and adults—just weird, siloed clans of barely differentiated humans yelling at screens and each other, staying alive by outrunning boredom with strange and clumsy new rituals (wiping down groceries, doing Sunday family dinners on Zoom) while reading about the deaths of thousands or being assured that things will soon get back to normal.

The rewards of post-college transition do not come from the achievement of goals, of imposing one’s will and making life listen to you, but rather from the wisdom of understanding what happens when you listen to life and learn to trust your ability to respond effectively. Life is making some very strange, tormented, muffled sounds right now. But through my graduate research and professional clinical experience, I have learned that the people who maintain their ability to listen and make room to reflect while traversing the crucible of life’s transitions are better able to receive the wisdom that we must all relearn now as we come through the Covid-19 transformation.

There is no single defining moment that makes us an adult, and no external marker of our success at becoming one. Similarly, there will be no single, defining moment that tells us when the Covid-19 transformation is over, and no one will be handing out certifications or special commendations allowing us to know if we have met expectations as well or better than our peers. Adulthood is realized in the aggregate of a series of untraceable points that quietly allow us to stop looking for proof of its existence. Over time these things add up, allowing us to realize we are adults.

A comparable realization will be made as we tolerate the Covid-19 transformation. We need to be creating the internal conditions that will allow us to see it, individually and collectively.

It was my inability to see the signs, and my complete misunderstanding of what constitutes adulthood, that brought me to that kitchen in San Francisco 25 years ago. In truth, I thought it would add a dash of virtue to my story, a bit of grittiness in a life that had otherwise been too smooth and easy. Luckily, the values my parents instilled in me allowed me to confront the shame of my deceit and set me along a winding path toward usefulness.

There is no shame in not knowing what to do at this time. The best thing we can do is discover how we can be most useful to each other as we gradually forge our way forward, together.