Covid-19 is a problem for elevators. Is the paternoster lift the solution?

An elevator is the perfect incubator for an airborne virus in many ways. So how can we safely shuttle people in these crowded, sealed-off boxes? It remains an unresolved question on the post-pandemic reopening checklist.

An elevator is the perfect incubator for an airborne virus in many ways. So how can we safely shuttle people in these crowded, sealed-off boxes? It remains an unresolved question on the post-pandemic reopening checklist.

The range of DIY elevator solutions are unconvincing, even comical: dividing the floor with tape for social distancing, gluing hand sanitizers on handrails, asking people to face the walls, or using fobs and metal pins instead of fingers to press buttons. Salesforce’s Seoul office has a “Disneyland-style ticketing system,” limiting elevator rides to two to four occupants per trip, which results in a lot of energy waste and queuing.

What all of these solutions has in common is that they hinge on appealing to each passenger’s sense of caution—a system that’s inherently not foolproof.

Now, architects at The Manser Practice in London are offering a curious engineering solution: bring back single-occupancy elevators.

Painting a post-pandemic scenario for hotels, the firm proposes modernizing the Victorian-era elevator model called the paternoster lift. “We see a potential for the good old paternoster lift to be modernized, which could not only move people around more efficiently,” Manser explained to Dezeen. “In some hotels, [it can] add to the theatricality of the central space.”

The design of the original paternoster is certainly dramatic, if crudely so. Custom designed by architect Peter Ellis in 1868 for Liverpool’s Oriel Chambers office building (a polarizing modernist landmark), it features a series of small, open compartments moving continuously in a loop up and down the five-story structure. Passengers never have to fuss with buttons, they simply hop on when they see an open compartment and disembark when they reach their floor. The mechanism is akin to ferris wheel carts or “car machines” in urban parking lots that hoist vehicles up a tight space.

“In the 1900s, the paternoster demonstrated visual modernity,” Jeannot Simmen writes in Elevation: A cultural history of the elevators. “All other vehicles required coachmen, guides, conductors or elevator attendants. Only the all-round elevator showed a transport system in a simple arrangement without a guard and without doors… New and very functional, this required a spontaneous action when getting in and out: the courageous jump, with momentum, holding on to the handle creates an elegant entry.”

One BBC experiment proved how the paternoster—”our father,” in Latin, a reference meant to evoke the lift system’s similarity in shape to rosary beads—moves people much faster than traditional elevators. Using the University of Sheffield’s paternoster (the world’s tallest) the BBC demonstrated how 50 students can travel 18 floors up in less than 10 minutes. In comparison, the school’s conventional lift managed to transport only 10 students in the same amount of time.

Efficiency-loving Germans also have a particular affection for paternosters. Called personenumlaufaufzüge or people movers, many paternosters were installed in government buildings. Their nickname, beamtenbagger, means “civil servant excavator.”

A history of mishaps

Ellis derived the paternoster’s name from the first two words of the Lord’s prayer. Critics note that Ellis chose the perfect name for his invention, for it would be useful to utter a plea for divine assistance when getting on the notoriously dangerous “guillotine” lift.

As Simmen describes, physical coordination and a sense of timing are needed to get in and out of the paternoster, like catching an escalator step or getting on a ferris wheel. They’re impossible for people in wheelchairs or on crutches, or anyone with a baby carriage.

Tales of paternoster mishaps abound: falling in, broken limbs, even a fatal accident that resulted in a European ban on new paternosters in the 1970s. In 2015, Germans were consumed by a proposal that would require people to obtain a license before being allowed to board one of the country’s antique paternosters.

Simmen, the elevator scholar, tells Quartz at Work he believes that the paternoster ought to remain a relic of the past. “Paternosters are dangerous today,” compared to normal elevator systems, which have become relatively (though not totally) foolproof, he explains. Simmen attributes the shift toward building more automated, accident-free environments to the prevalence of potential paternoster calamities.

The previous generations were well versed: In Hamburg, people jumped on the ship, jumped off the tram at the right place and the approaching bus was reached with a sprint. At that time there were still running boards and doors that could be opened yourself.

Today, automated doors that tightly closed open after standstill [like subway doors]. Equipped with sensors so that even the smallest finger doesn’t get scratched, we are so well protected…

Despite safety concerns, there are paternoster diehards.

“The paternoster has lodged itself in my imagination, to the extent that I’ve now written one into a novel,” notes Mark Blacklock, who liked riding in the famous lift at Sheffield when he was a student there in the early 1990s. Writing in Granta, he explains that “[t]o step into a paternoster lift is to step into the circulatory system of a building, to become a part of its very structure.”

Like cataloguers of beleaguered animal species, paternoster preservationists have produced maps of the approximately 300 active paternoster lifts in operation around the world. Bryan Armitage, a lift safety engineer interviewed by the BBC, said the University of Sheffield’s refurbished circular lift presents little danger. “There are actually 140 ways to stop this lift but only one way to start it,” he said.

Paternosters for the pandemic?

So does a paternoster revival have a chance for the coronavirus era? Elevator companies Hitachi and Thyssenkrupp are among the elevator companies revisiting Ellis’s invention.

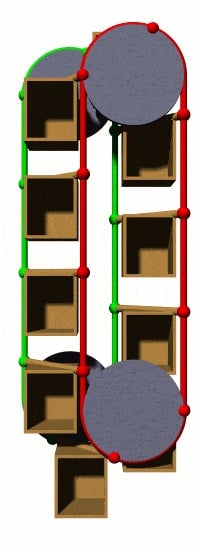

In 2014, Hitachi debuted a prototype for the Circulating Multi-car Elevator System, a modified paternoster with doors, user-controlled entry, and a slate of safety features. Instead of compartments traveling on one continuous rope, sets of two machine-controlled elevator cars act as counterweights, allowing each car to start and stop independently.

The Berlin-based solar manufacturing company Solon SE got a special permit to install a paternoster at its headquarters in 2009—”the first cyclic elevator system installed anywhere in decades,” reports Peter Fairley for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ blog. Working with the German office of occupational safety, Solon SE commissioned elevator contractor Schoppe-Keil and engineering certification firm TÜV to develop a disaster-proof model. The one-of-a-kind paternoster has red and green lights to signal to passengers when they should jump in. The lifts were designed to automatically stop when someone attempts to get in after the red light.

German firm Thyssenkrupp’s MULTI model, which can move both vertically and horizontally, is based on the paternoster’s mechanics. Its cars can accommodate more people than traditional paternosters, but they’re designed to be small enough to allowing people to travel faster. “The idea of a paternoster is still a good one when it comes to having multiple cabins per shaft,” a Thyssenkrupp spokesperson tells Quartz.

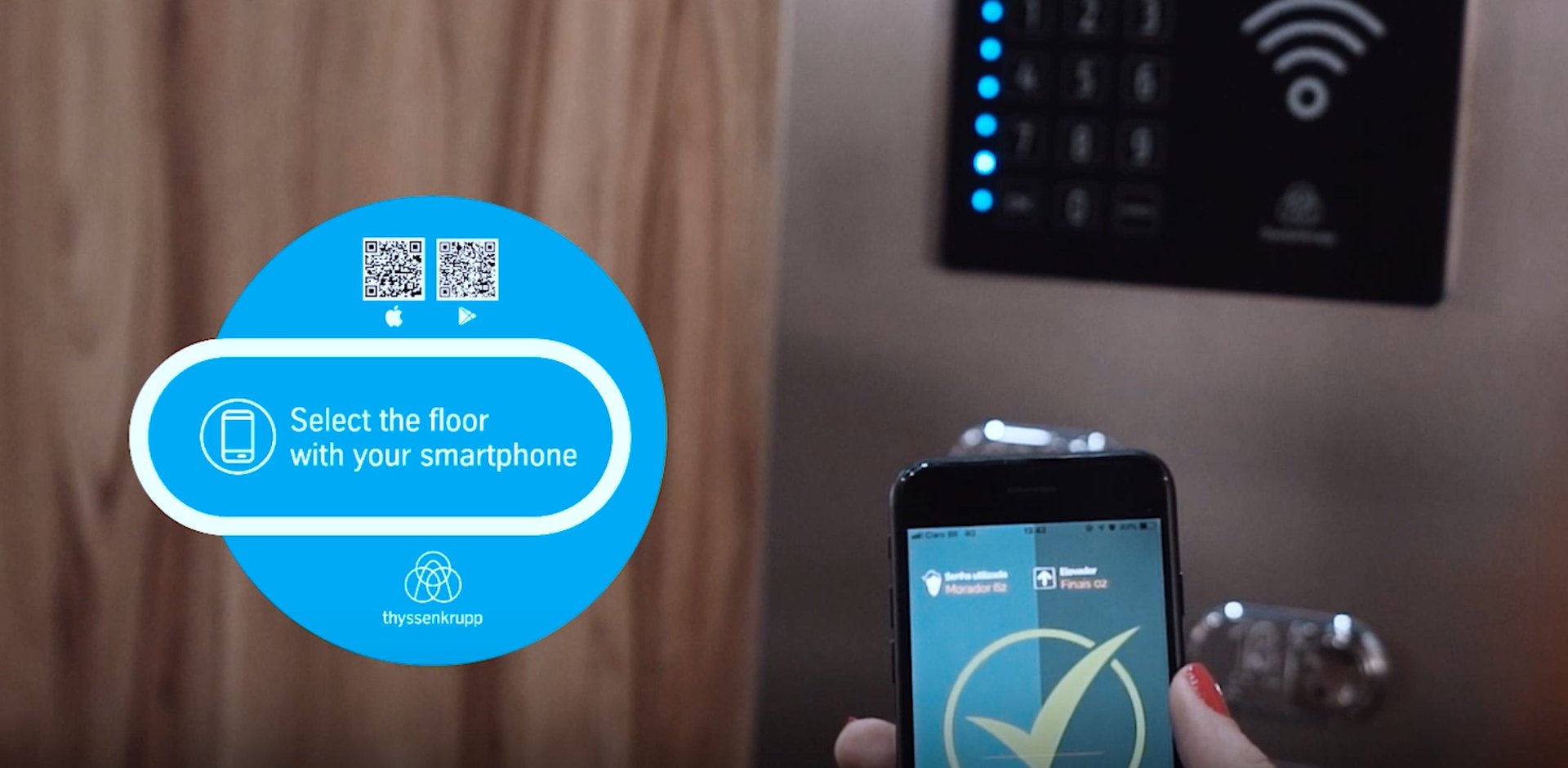

As companies consider retooling old models, Thyssenkrupp is also focused on retrofitting conventional elevator cabins for the pandemic. This week, the company unveiled a “touchless” model with germ-free surfaces, thermal cameras to detect passenger temperatures, and a built-in air purification system.

Thyssenkrupp’s coronavirus design solution also addressed another long-standing elevator user-experience problem: confusing buttons. The new elevator cars let passengers select floors via a tap on their mobile app or a kick button. “Touchless technologies are highly relevant,” explains Peter Walker, CEO of Thyssenkrupp, in a press statement. “Using a special kick button the passenger can call a cabin with a simple toe tap instead of touching a pad or button by hand.”