Milton Glaser’s brilliant last year

Shortly after moving into a new studio on West 21st street in Manhattan, Milton Glaser got a strange phone call. On the line was a reporter for The Washington Post asking to fact-check details of his obituary.

Shortly after moving into a new studio on West 21st street in Manhattan, Milton Glaser got a strange phone call. On the line was a reporter for The Washington Post asking to fact-check details of his obituary.

The celebrated graphic designer had just turned 90 years old, perhaps defying expectations that he would live so long given his battle with kidney disease and a cornucopia of small pains and ticks that appear with age. After patiently answering questions for nearly 15 minutes, Glaser, with a twinkle in his eye, hung up and said to me, “They must know something I don’t.”

Glaser would in fact continue to live, work, and produce projects for nearly a year after that phone call. He died on June 26, his 91st birthday.

I grew to know Glaser, who co-founded New York Magazine in the late 1960s, while working with him on a book last year about his iconic work in magazine design with his business partner, Walter Bernard. Glaser later asked me to stay on to write his autobiographical “last big book” as he called it. As a journalist, I sometimes felt that perhaps I, too, ought to compose a pre-obituary on Glaser.

What is a pre-obituary? A pre-obit is an homage to the “pre-dead,” as former New York Times obituary writer Margalit Fox once wryly put it. It’s an efficient newsroom practice, whereby a proper obituary is written in advance of a celebrated figure’s death. “If an advance has gone according to plan, it has been researched, written, fact-checked, filed, edited, and copy-edited, laid out on a page and sometimes even supplied with accompanying videos for online viewing, all well ahead of the game,” Fox explained in a “Times Insider” piece. “Then, when the time comes, a writer or editor has only to drop in the ‘when,’ the ‘where’ and the ‘how’ of the death, an act known in obituary parlance as “putting the top on the story.”

Fox’s 2014 explainer revealed that the Times has more than 1,700 pre-obits on file—and true enough, Glaser’s fully illustrated, 1,600-word obituary was up on the newspaper’s website shortly after the details of his passing were confirmed. Skimming the long article with a heavy heart, I remembered why I decided against writing a final essay about this genius.

During his last years, Glaser remained curious, experimental, and eager for reinvention. With illustrator Ignacio Serrano as his collaborator and computer operator, he experimented with layering dots over drawings. He redrew alternative versions of William Shakespeare’s portrait, exhibiting his acuity as an artist and an iconoclast. He finished three children’s books and took on commissions—from flan packaging for a family-owned business to advocacy posters, and designs for the Theatre for a New Audience.

Glaser even joined the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s call for artists, pitching one of his dotty landscape paintings for a subway station. He had experience after all, having designed a wall mural for the Astor Place station in 1986. The MTA didn’t choose his newer design, but it seemed premature to put a period on his career, foreclosing on any new tricks his lively mind would conjure.

Interviewers dogged Glaser about projects he completed decades ago, including the psychedelic Bob Dylan poster (1966) and the I ❤ NY logo (1977). This was a nuisance for someone who craved constant reinvention. The worst type of clients would ask him to reproduce something in a style he already had done.

The chance to design something that could spark cultural change gave Glaser a reason to get up each morning. “I have a secret,” he wrote in a book about his poster-design work. “All my life I’ve wanted my work to go beyond professionalism and enter the world of art. Every time I get a poster assignment, I hope that after I solve the client’s problem, I might be able to solve mine. Persian rugs and Chinese ceramics, among many other things, prove it’s possible.”

Before his death, Glaser was brewing a typographic tonic for the melancholy and estrangement the pandemic has brought. “Together,” Glaser explained to the Times, was meant as a reminder of our “collective consciousness.”

“If we realize we are all related and we need one another, that would be the best thing that could happen,” he said.

In his last years, design projects—whether self-initiated or commissioned—kept Glaser alive, engaged, and present. The office was a paradise, away from the bland hell of hospitals, waiting rooms, and dialysis centers. He capped each work day by saying, “A domani. Tomorrow, we begin again.”

A life in review, twice over

Truth be told, I rejected the idea of writing my own pre-obituary of Glaser for selfish reasons. Drafting it would be a reminder that his vitality wasn’t infinite—a fact which those who loved and admired him would have to reckon with eventually. Yes, eventually, I thought. But not then.

In his final year, at least two things remained perfect for Glaser: his mind and his hands. “You gotta keep these in good condition,” he would say, flexing his long, elegant hands spared from arthritis. In December, he showed me a portrait he’d been working on of Jeffrey Horowitz, director of the Theatre for a New Audience. Compared to previous drawings, the lines appeared shakier than other things I’d seen him produce. Like Matisse, he explained, you lean into what your body can do. Glaser, of course, was alluding to the French Impressionist’s cut paper collages produced late in life, when he could no longer paint. “It’s a transition, not a loss,” he said. I marked it on my notebook as Glaser’s exciting new squiggly art period.

There are in fact, countless, overlapping periods in Glaser’s career.

My stint at Glaser’s studio coincided with a momentous office move for him. After 54 years, he was selling his four-story townhouse on East 32nd Street, largely because climbing the walk-up was just too punishing for his knees. The relocation plans entailed the Sisyphean task of sorting through file cabinets, drawers, storage boxes, shelves of sketchbooks, office correspondence, fan mail, 35mm Kodachrome slides, sentimental tchotchkes, and about 250,000 posters in the basement—the paper trail of an adventurous, multi-faceted life.

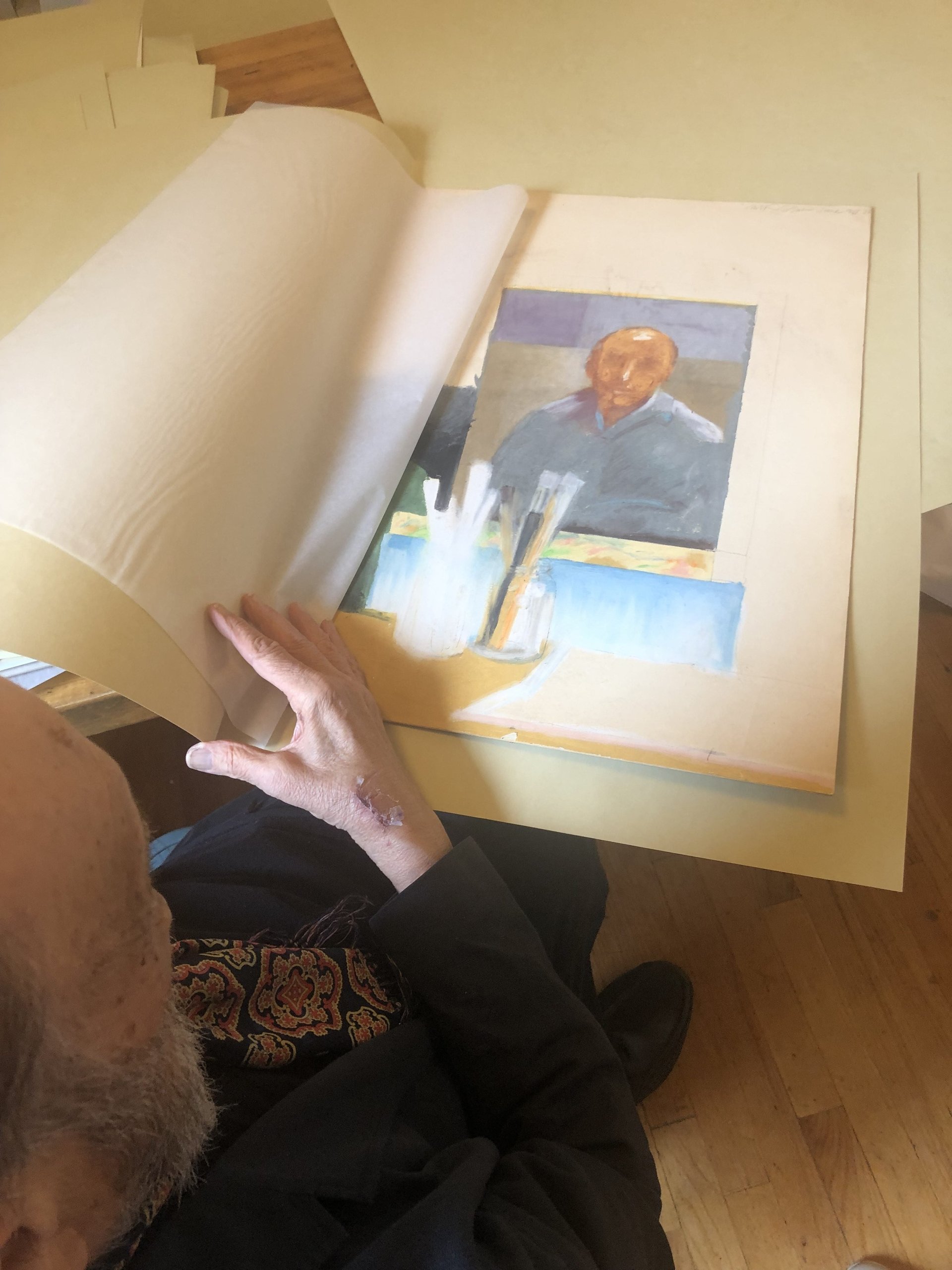

Each day, Serrano or I, or Xiao Hua Yang, an illustrator who was recruited to help with the move, would present Glaser with piles of large, green file folders, filled with his drawings to review. With the decisiveness of a general, he separated sketches into four piles: scan, archive, personal or trash. (“Scan” meant flagging a drawing for the book we were working on, and the archive pile was meant for the archives at the School of Visual Arts. Sometimes, we disobeyed his “trash” orders and snuck the piece in the archive pile.)

Watching Glaser evaluate his own work was unforgettable. “Not bad,” he would say, reviewing an intricate cross-hatched illustration. “I’m not very good with likeness,” he declared, eyeing a sketch of Fats Domino, Nina Simone or one of the many portraits he drew for album covers and magazine articles. Sometimes, he would wrinkle his nose quizzically at a forgettable poster. “Did I do this?”

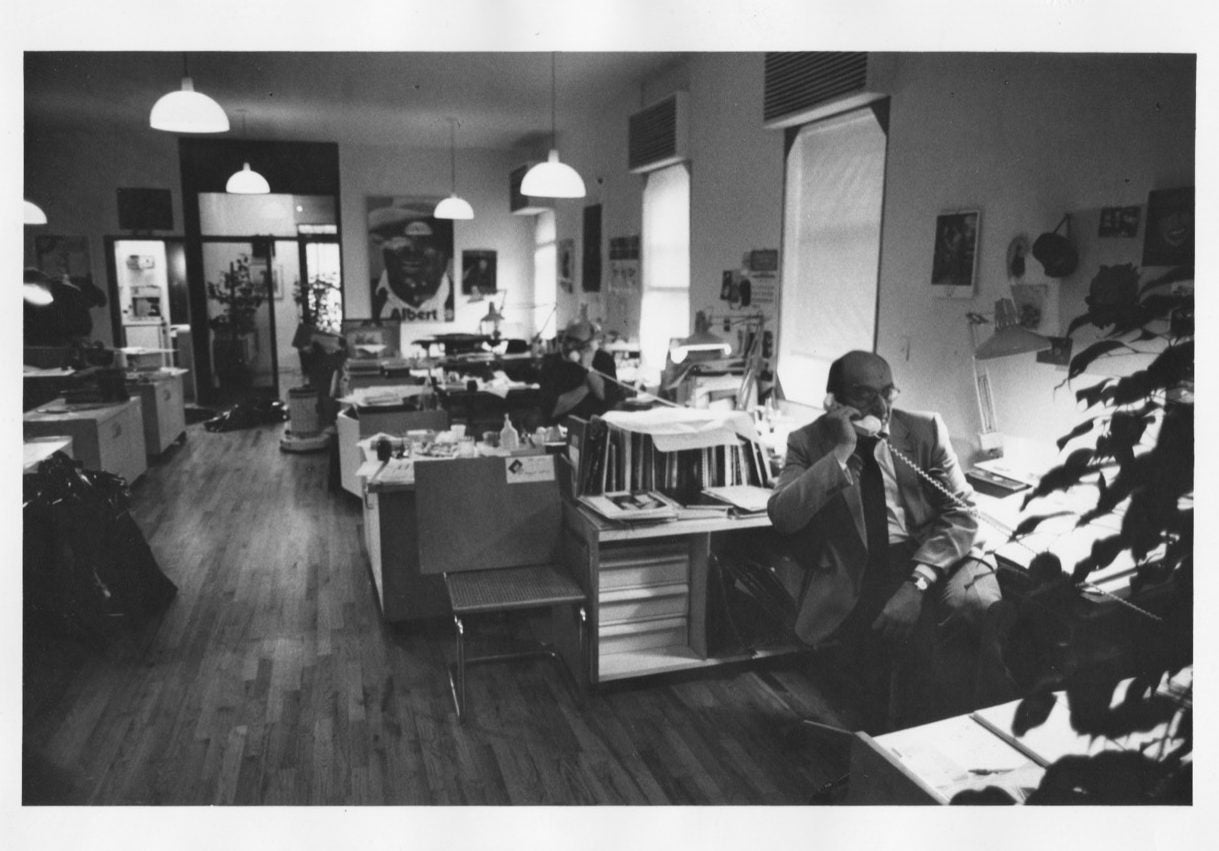

Leafing through old photographs, I often wondered how Glaser’s personality changed through these periods, like his form-shifting body of work. There’s an early sepia-toned picture of a kid dressed in a bonnet and a perfectly fitted suit (his father was a tailor after all). Then, the lanky “Milty” in his high school yearbook photo; followed by the dreamy-eyed student in Italy, so in love with his new wife. Thanks to Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone, a former assistant at Glaser and his design partners’ Push Pin Studios, there’s a box full of candid pictures of Glaser in the office—taking a phone call while touching up a drawing, mulling a cover for New York, or having lunch at a dive restaurant for Underground Gourmet, a popular column he co-wrote with Jerome Snyder for the magazine.

His out-of-office life was well-documented, too. A softer, more casual aspect shines through in photographs of Glaser at his whimsical summer home in Woodstock, New York. There’s a curious moment in the mid-1960s, when he was part of an ashram with guru Swami Rudrananda, whom everyone knew as”Rudi.”

I’ve heard former employees whisper at how big an ego Glaser had while running his own practice. (Glaser left Push Pin in 1975.) I only knew him as a gentle, insightful, courageous, cost-conscious, and largely joyful man.

After he died, I glimpsed a crowdsourced slideshow on Glaser’s impact while managing his Instagram account—a heartbreaking and singular privilege. He would’ve found so much amusement in each message, I thought. On his 90th birthday, he asked me to help him reply to each email, Instagram, and Facebook message with a thank-you note that he sketched and scanned. “Why not just post this once? Everyone who receives this might think you drew this for them,” I said, my hand cramping from clicking and attaching the same jpeg many times over. “Well, that’s the point,” he smiled.

Hundreds and hundreds of tributes from friends, former students, clients, and strangers pour in to this day. Because he died on the evening of his birthday, for a while his Instagram feed was a strange mix of jubilation and sorrow. The common denominator, I concluded, was love.

Design as a meditation on love

I recently tried to encapsulate Glaser’s career for a friend who didn’t work in the design industry. “So, he’s the Michael Jordan of design,” he suggested. Yes, but so much more.

Ultimately, Glaser’s life was a meditation on the nature of love. Earning an audience’s favor was the electricity that coursed through his work. “The key to designing magazines and supermarkets is affection,” he told me. ‘You have to make people feel that they like it, in a personal way. The emotional dimension of communication is very powerful.” Conjuring love for an evil brand or enterprise is the ethical reckoning every designer must face, as Glaser outlines in his 2004 essay “Ambiguity and Truth.”

Most of us here today are in the transmission business. While we don’t often originate the content of what we transmit, we are an essential part of communicating ideas to a public that is affected by what we say. Should telling the truth be a fundamental requirement of this role? … While marketing is obsessed with the way groups behave it doesn’t generally conceive of those groups as being our fathers, mothers, sisters or friends, this would make the job far too complex. Rather, these groups are thought of as ‘markets’ with generalized characteristics that make manipulating them seem ethically acceptable.

Hanging on a back wall of Glaser’s design studio is a small board with a quote by the Irish novelist Iris Murdoch: “Love is the extremely hard realization that something other than oneself is real.”

He expanded on this philosophy, in an interview filmed two years ago: “The only thing that matters in life is your relationship with other human beings. Fame, money, reputation is bullshit,” he said.”I read something recently that was very moving to me. A group of people were talking about expressing love…Someone said, ‘In my country there’s no word for love.’ ‘So what do you say instead,’ others asked. He replied, ‘We say, I see you.’”

“Suddenly, I got it,” Glaser explained. “Merely to see the person in front of you is as close as you’ll ever get to loving somebody.”

Nearly two weeks has passed since Glaser’s death. I’m grateful to have been an eye witness to his work, his wisdom, and occasional folly. I see him still.