The herculean effort it takes to maintain the Met museum during a lockdown

For nearly six months, the rattling of cleaning carts and the pitter-patter of a skeleton crew of custodians were the only sounds at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This was a stark contrast from the over 7 million visitors who trooped through New York City’s iconic 150-year old art institution prior to the pandemic. The Met, which closed all three of its branches in early March, was among the first cultural institutions in the city to voluntarily close when Covid-19 cases began spiking.

For nearly six months, the rattling of cleaning carts and the pitter-patter of a skeleton crew of custodians were the only sounds at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This was a stark contrast from the over 7 million visitors who trooped through New York City’s iconic 150-year old art institution prior to the pandemic. The Met, which closed all three of its branches in early March, was among the first cultural institutions in the city to voluntarily close when Covid-19 cases began spiking.

As New York’s premiere art institution and the third most visited museum in the world, after the Louvre and the National Museum of China, many art lovers and smaller cultural institutions wondered how the mega museum would fare during the pandemic. Its closure, ahead of the statewide mandatory shut-down of non-essential businesses and a day before US president Donald Trump declared a national state of emergency, served as a bellwether of the worsening crisis in New York.

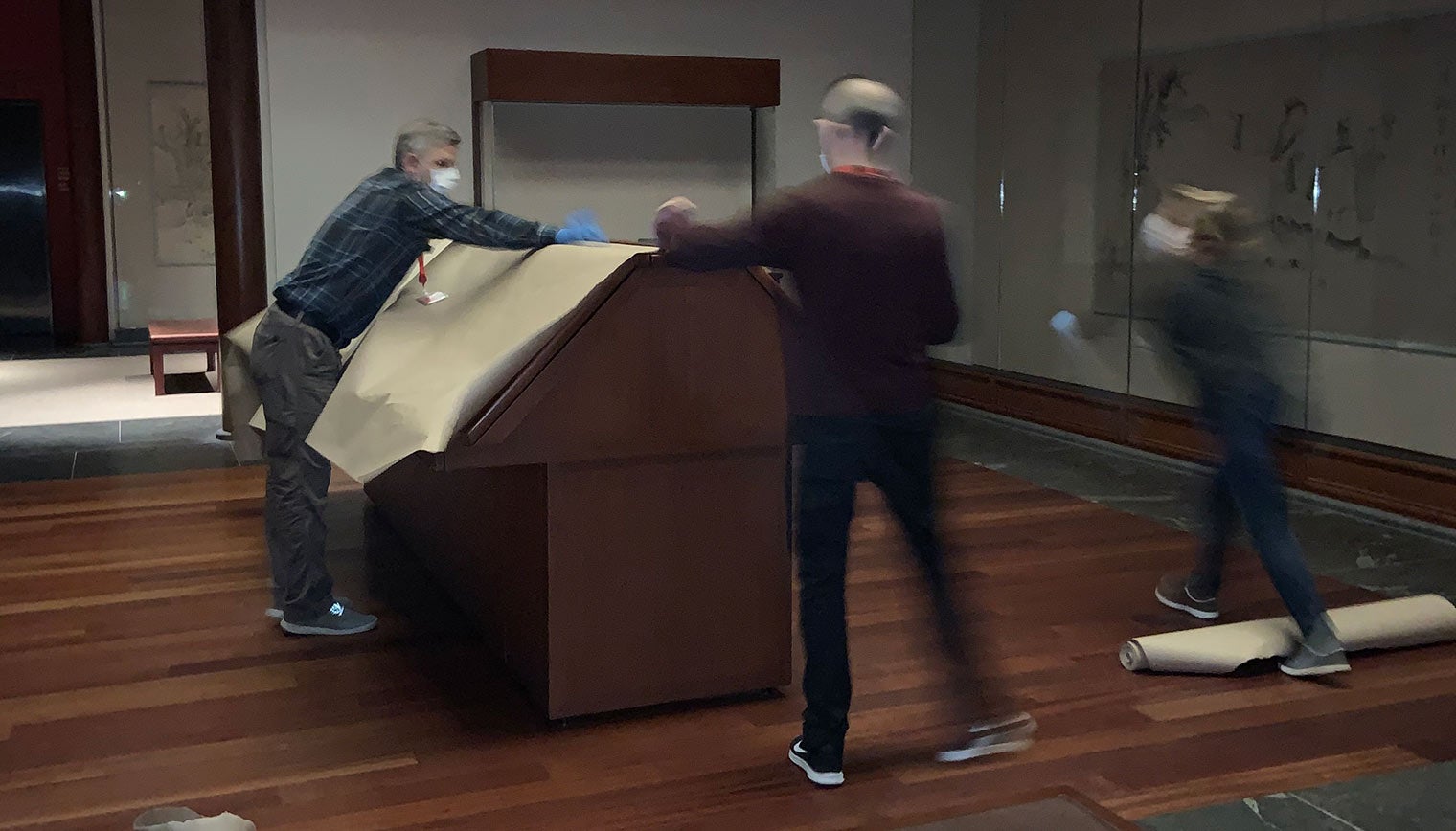

Shutting down the Met is no simple matter. With more than two million works representing 5,000 years of art stored across three facilities—the main museum on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, the Cloisters in upper Manhattan and the Breuer on Madison Avenue (now permanently closed)—it took teams of caretakers and a network of remote workers to keep it intact during the lockdown. Fragile works are vulnerable to pests, changes in temperature, and exposure to light, all of which demands constant vigilance.

When the Met reopened late last month, after 169 days in the dark, Daniel Weiss, the museum’s president and CEO, made a point to acknowledge the crews who watched over the collection and the rest of its staff who swiftly adapted to new demands of working remotely. “I want to recognize the exceptional work that has continued throughout the museum’s closure,” said Weiss at a virtual press conference. “The Met is far more than its buildings or even its collections. It is a community of exceptional people, experts on all manner of subjects—educators, scholars, conservators, editors, administrators, maintainers, art handlers, custodians, engineers, and so many more.”

Even with its $3 billion endowment, reopening the Met was not a given, as art institutions around the world have found it impossible to open their doors. New York’s Metropolitan Opera, one of the nation’s largest performing arts organizations, announced this week it was canceling its 2020-21 season and won’t open until later next year. The fate of Broadway theaters remain uncertain. According to a July survey, a third of US museums may not survive the year.

For staff members, the museum’s highly-anticipated reopening was an emotional moment during a particularly devastating period in its history. Anticipating over $150 million losses this year, it had to layoff 20% of its 2,000-person workforce, the New York Times reported.

Only 40 essential staffer were allowed to enter the Met’s main building while it was closed. Donning face masks, gloves and observing social distancing protocols, they patrolled the galleries to make sure that the collection was safe. Collection monitors often began their rounds by feeding the koi fish in the Chinese scholar’s garden—the “fun part of the day,” as C. Griffith Mann, curator-in-charge of the medieval department, shared in a video.

“To be inside the empty museum at this historic time felt sad and eerie,” wrote Jim Moske, the Met’s managing archivist in a blog post. “The magical silence that surrounded the artwork was deeper and richer than what I’ve heard during closed-hours of ordinary days.”

Angela Reynolds, who oversees the maintenance department, recalls how the museum’s custodial crew came together during this strange time. “The buildings department always knew they were essential, but it was at that moment they became the museum’s masked heroes,” Reynolds writes, describing how they routinely disinfected every nook of the museum’s 2 million square feet. “Eye contact became an obligation for effective communication…With voices muddled by the masks, there was no more walking away while someone was speaking. We were all connected.”

Marc Montefusco, the Met Cloisters’ new chief horticulturist was just days into the job when the museum shut down. “My first few days were just wonderful,” he tells Quartz. “I was thinking that this is just the greatest thing in the world, then a week and a half later it all came to a grinding halt.”

Montefusco says he lobbied to be part of the Met’s essential crew, anticipating the longterm problems if the Cloisters’ three gardens were left untended. He and two gardeners went to work in upper Manhattan nearly every day during the closure. One singular benefit: Witnessing 30,000 flower bulbs bloom, as planned. “The good news is that the gardens met expectations wonderfully; the bad news is nobody got to see this masterwork—the incredible planning and physical labor,” he describes. For the museum’s reopening the gardeners planted flowers and herbs depicted in the Cloisters’s famous Unicorn Tapestries.

The Met’s handling of the pandemic gave Montefusco “positive feelings” about his new employer. “I had been a Met fan boy from the day that I got notification that I was going to get the job and that has not changed one iota,” he explains. “It has been a real privilege to serve as steward, guardian, custodian or whatever word you like in that interim period.”

It wasn’t just the pandemic that shook the Met’s staff this year. Like the rest of the US, the clamor for racial justice reverberated throughout the institution. “Employees began having heart-to-heart conversations about racism and police brutality. The protest against racism became one of the biggest acts of global diversity and inclusion I’ve ever witnessed,” explains Reynolds.”The Met’s staff is evidence of diversity achieved however, inclusion is where many of us have missed the mark, often mistaking movement for progress.”

Keith Christiansen, a long-time curator at the Met, received a hailstorm of criticism for an incendiary Instagram post (his account has been deleted), criticizing efforts to remove confederate and colonialist statues across the US, amid the George Floyd protests.

This reckoning resulted in a 13-point resolution to fix systemic inequities throughout the institution.

Today, museum visitors can trace fragments of the Met’s mea culpa in Making The Met, 1870–2020, its marquee anniversary exhibition. They revised the wall text to acknowledge the museum’s curatorial bias over its 150 year history. The exhibition, for instance, points to how they ignored the Harlem Renaissance and that one of its major donors, the Havemeyer family, accumulated wealth from the slave trade.

Visitors may also note a new wall display that lists the names of every single person currently working at the museum. It’s a public tribute to the mostly unseen work of administrative, curatorial, security and janitorial staff who keep it all running.