A new book on WeWork reveals the confidence skill we really need

Conventional wisdom holds that professionals need to project confidence to be successful. Plenty of books, career-coaching classes, and body-language tips aim to help people do just that.

Conventional wisdom holds that professionals need to project confidence to be successful. Plenty of books, career-coaching classes, and body-language tips aim to help people do just that.

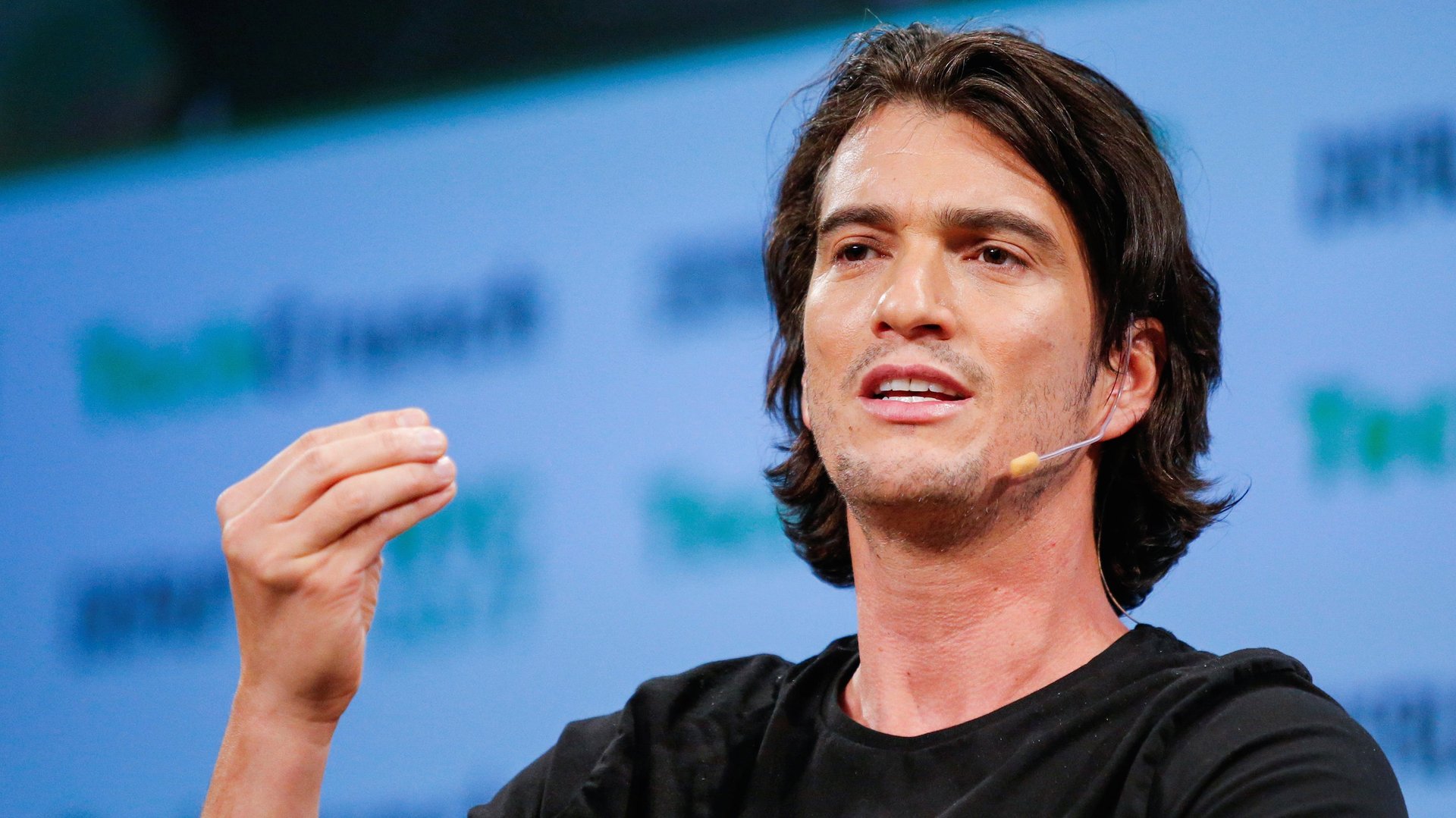

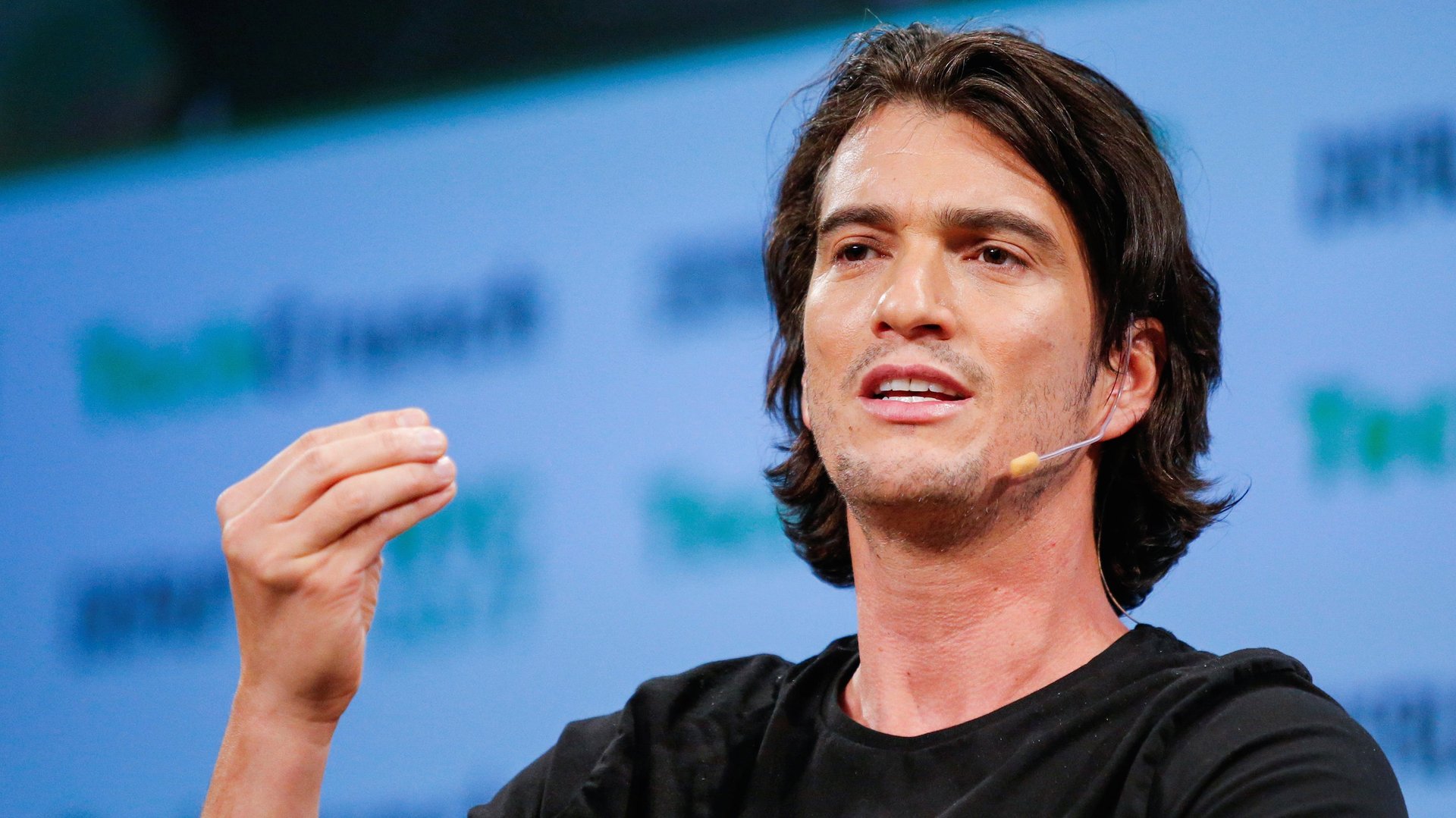

But as the new book Billion Dollar Loser reveals, confidence—as embodied in the megalomaniacal figure of WeWork co-founder and ex-CEO Adam Neumann—is overrated.

As author Reeves Wiedeman tells it, Neumann’s extreme confidence in his own abilities propelled WeWork to achieve an absurdly inflated $47 billion valuation. (As of March 2020, in the aftermath of the company’s failed IPO and at the onset of Covid-19, WeWork’s valuation had fallen to $2.9 billion.)

Neumann talked about building WeWork cities by 2028 and tried to convince Elon Musk that he’d need WeWork communities on Mars. He pondered becoming president of the US or even the world, although he was disqualified from the former by virtue of being born in Israel and from the latter because the position is imaginary.

Above all, Neumann was confident about WeWork’s future. “Our trajectory looks like Amazon’s,” Neumann told Wiedeman in April 2019. “Except our market is larger and our growth is faster.” By the end of the year, he’d been ousted as CEO, and his company was falling apart.

The confidence skill we really need

Neumann’s self-assurance had nothing to do with his ability to execute on his larger-than-life ambitions. If anything, it was a warning sign of hubris that people around him repeatedly failed to heed. But as Munich Business School professor Jack Nasher explained in 2019 in the Harvard Business Review, “people are simply not great at assessing competence.” Instead, we tend to rely on confidence as a sign of ability—even when there is little evidence to support someone’s bold claims.

If people can be so easily and erroneously swayed by confidence, perhaps we should spend less time trying to project it ourselves, and more time learning to be skeptical of the quality in others.

Such a skill would have certainly saved WeWork investors a lot of money. The company’s most important investors were all swayed by faith in Neumann’s personality far more than by his business plan—not because they were foolish, but because venture capitalism “dictated that you bet on entrepreneurs as much as their companies,” as Wiedeman writes. They were willing to look past WeWork’s overspending and governance issues, not to mention the fact that it was fundamentally a real-estate company and not a tech company as it claimed, because Neumann promised investors he was going to take over the world. He sounded so sure of himself that it only seemed logical to believe him.

Blinded by confidence

In Billion Dollar Loser’s telling, the downfall of WeWork can be attributed as much to Neumann’s enablers as to the man himself. “As WeWork employees surveyed the wreckage,” Wiedeman writes, “they couldn’t help feeling that Neumann wasn’t the only one to blame. They had been assured that there were adults in the room.”

Benchmark Capital partner Bruce Dunlevie, who once compared Neumann to a “new-age Bezos,” explains the thinking behind the venture capital firm’s $16.5 million initial Series A investment as, “Let’s give him some money. He’ll figure it out.” Japanese billionaire Masayoshi Son, the founder of SoftBank, poured nearly $20 billion into WeWork largely because, as Wiedeman puts it, he was looking for younger versions of himself—“entrepreneurs with a sparkle in their eyes and a willingness to act a little crazy.” On that, at least Neumann delivered.