The toll pandemic isolation took on me and my autistic son

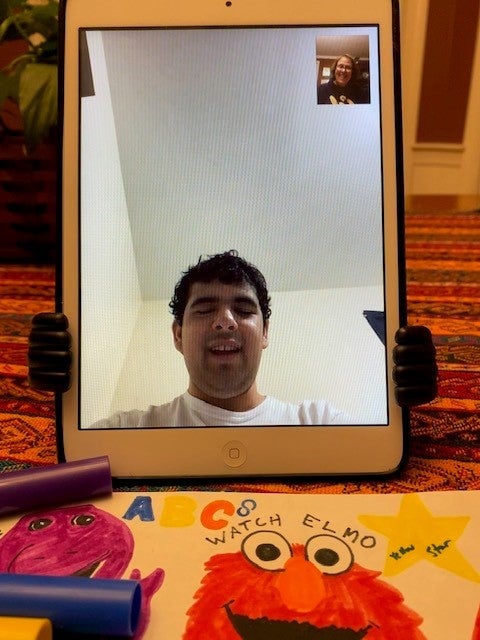

With markers and a sheet of paper in hand, I call my special-needs son on the iPad and settle in for an hour of chatting and drawing. Framed by the small screen, 20-year-old Dylan directs the conversation and dictates the night’s roster of shapes.

With markers and a sheet of paper in hand, I call my special-needs son on the iPad and settle in for an hour of chatting and drawing. Framed by the small screen, 20-year-old Dylan directs the conversation and dictates the night’s roster of shapes.

“Hi Mommy, Y in the sky,” he says, expecting me to respond “T in the sky”—clearly mumbo-jumbo to outsiders, though it makes perfect sense to me. Dylan, who is severely impacted by autism, is referring to the shapes of the street lights he observes when we drive around town.

These nightly sessions have been the extent of our communications over much of the past year. The pandemic sent his residential school in Massachusetts into lockdown last March. By mid-July, he was able to come home again on weekends, but a spike in new cases in January led to a renewed lockdown and we were back to our virtual chats.

Dylan and I have always connected through our pictures. There are far better artists in the house, but only I am permitted by him to put pen to paper. The drawings have taken on a deeper meaning for both of us during the pandemic. Every few weeks I drop off a care package of his favorite snacks along with a few drawings. One of Dylan’s teachers told me he keeps several on his desk at school. “He won’t even let us touch the pictures — they’re off limits,” she said. “It’s like his way of holding onto home and you two. Very beautiful.”

For me, the calls are mentally exhausting because of Dylan’s perseverative chatter, as he repeats the same words and phrases, day in and day out. He has a limited vocabulary and doesn’t speak expressively. If I push him to talk to his twin brother Cameron, he’ll both ask a question and answer it: “How are you? I’m fine.” Still, I have to see my boy and draw for him and I rarely miss a night. I’d come to grips with our partial separation when he moved to the school three years ago , but when Covid cut off all access, it was almost too much to bear. We’d never been apart longer than a week and I cringe a little every night when he asks me on screen for a “mommy hug.”

Tonight, we get down to business and Dylan gives me a run-down of my assignment. I’m to draw purple hexagons, yellow stars, blue squares, two Barneys, two Elmos, a train and a bus. I’m also mandated to write the color and name of each. I’ve wondered how much he understands about the pandemic and figured not much, though he asks me to draw masks on the shapes.

Since he refuses to draw himself, I make Dylan spell all the shapes as a way to redirect him from his repetitive banter. When done, I hold my creation up to the iPad. He must have inherited some of my editor genes because he carefully reviews and points out every mistake.

Raising a son with severe autism

Dylan moved into the school in the summer of 2018, when he was 17. It was one of the most difficult times of my life. Of course, hindsight is 20/20, and after getting used to our new normal, I knew it had been the best possible decision and outcome. Dylan was thriving and happy, as long as he knew he’d be home on weekends.

Our family had been sinking into an abyss in the years prior. Autism encompasses so many challenges, and they vary from person to person, but common threads are difficulty communicating and regulating emotions. Dylan could be fine and smiling one moment and then burst into tears or an angry fit the next. As he got older and bigger, it became harder to manage his frustrations. He would lash out at his father and brother, who’s also on the “spectrum” with high-functioning autism. At one point, Cameron told an aide at school that he didn’t feel safe at home. That was the first of two turning points.

I created a safety protocol. At times we could tell when Dylan’s behavior was likely to escalate. I would yell out “Code Red” and his brother would lock himself in the nearest bathroom or bedroom. My husband would go to the basement and I would stay with Dylan, making sure he didn’t hurt himself. He had hit me in the past, but rarely.

When he flew into a rage, Dylan would scream “hitting Camy” and “hitting Baba,” which is father in Turkish. He would slam his bedroom door so often and so hard that the frame loosened from the wall. One time, he accidentally punched a hole in the door from inside his room. We still haven’t replaced the door and two big metallic cardboard stars cover the hole.

My husband, a big, strong guy, fulfilled his Turkish military service in the 1980s commanding 40 soldiers on a remote post along the border with the Soviet Union. Months before we approached our school district about our situation, he said to me: “I’m a 60-year-old man, hiding behind furniture in the basement from my son.” That was the second turning point.

Probably from sheer exhaustion, Dylan would eventually give up and crumple into a heap of tears, slowly finding a path back to calm. We’d lie on our backs in his darkened bedroom and stare at the glow-in-the-dark stars on the ceiling. And he’d ask me to draw for him again—mostly stars this time—until he fell asleep.

Help in the form of a residential school

Fortunately the district agreed with our assessment that he needed more help and Dylan was approved for a residential placement. Massachusetts is known for its breadth of special needs services, but even so, demand can outpace supply. Somehow the stars aligned and a spot opened at an excellent program. A huge bonus: It was just 20 minutes away. That meant there would be continuity in Dylan’s life and he could come home often.

He transitioned quickly and well, and got in the groove of daily trips into the community—shopping, parks, movies. He got small jobs at school and then short shifts offsite with a job coach at organizations like Meals on Wheels and Mass Audubon.

I, on the other hand, was a mess. For my husband and Cameron, Dylan’s move brought a sense of relief. But I worried about his feelings. I had always been his champion, his advocate, his voice and I felt guilty not being able to care for him myself. I now had all this free time and didn’t know what to do with it, so I hibernated for a few months.

As it became clear that Dylan was going to be fine and the structured program suited him, I climbed out of my funk. Cameron came out of his, too. When Dylan started coming home on weekends, his behavior improved and I stopped anticipating a meltdown. The visits revolved around ice skating, his one true passion, and, of course, drawing.

We reserved our coloring sessions mostly to the weekends, but that abruptly changed with the lockdown. Because of his limited ability to converse, I needed a way to keep him engaged on the iPad, so my drawing for him became a nightly routine. There are hundreds of pictures crammed in two drawers in our dining room. I’ve saved every one of them. While I’m drawing, we sing—mostly nursery classics or theme songs from his favorite shows. Dylan changes a lyric now and then, his form of humor, and bursts into giggles.

I’ve learned a lot about my son during the pandemic. The biggest takeaway is how resilient he’s proven to be, and that makes me proud. It goes without saying this would be impossible without the incredible school and residential staff who’ve sacrificed their own wellbeing to take care of him and the others. Once a day Dylan would tell me “home soon.” When I said we’re waiting for it to be safe, he’d respond “yes” and move on.

Dylan got his second vaccine dose in March, and his latest lockdown ended recently— a year to the day when the first one began. We are reunited and drawing in person again. How nice it is to have him sitting next to me and I can follow through when he asks for a “Mommy hug.”