Major employers are starting to acknowledge the weight of working with cancer

Disney, Google, Microsoft, Marriott, and Meta are among the signatories of a pledge led by Publicis

“Hi Heather. There is a new initiative to support employees through cancer diagnoses and recovery launching next week at Davos... Dozens of major global brands and cancer charities have already signed up. Please let me know if you are interested in learning more.”

In fact, I was very interested in this pitch I received a few days ago, from a public relations agency. And my reasons ran far deeper than my thirst for good material to include in the newsletter I’m co-authoring this week from Davos.

Five years ago, as I was planning my first trip to the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. The connections I’d made in my professional life and the support my employer offered were inextricably tied to my experience and my recovery.

I was fortunate to work for Quartz, a company where I had no apprehensions in disclosing my illness. What I was less sure of—and one of the reasons I never shared my diagnosis widely—was whether future potential employers might learn of my cancer history from a Twitter or LinkedIn post and decide I wouldn’t be a good hire.

So, yes, I was intrigued to hear about a plan to make workplaces more supportive of people diagnosed with cancer. And I jumped at the chance, in the days leading up to the WEF’s 2023 meeting, to interview Arthur Sadoun. The CEO of the global advertising juggernaut Publicis Groupe, Sadoun had, a few months ago, disclosed that he was being treated for cancer. On Jan. 17 at Davos, Sadoun and his colleagues unveiled the Working With Cancer pledge, a global campaign organized by the Publicis Foundation.

An important wakeup call

I tend to roll my eyes when corporate leaders talk in hashtags, but the Working With Cancer pledge is launching with content that certainly spoke to me. Perhaps it will speak to you, too. Either way, there’s a good chance you’ll encounter it. The campaign is armed with $100 million in media spend, donated by pledge partners, Sadoun told me. And surely there are few people better positioned to make a marketing splash than the executives at Publicis.

Other companies that have signed on, pledging to provide open and supportive workplaces to people with cancer, include major employers like AbbVie, Adobe, AXA, Bank of America, BNP Paribas, BT, Carrefour, Citi, Disney, EE, Google, Haleon, L’Oréal, Lloyd’s, LVMH, Marriott, McDonald’s, Meta, Mondelez, Microsoft, MSD, Nestlé, Orange, Pepsico, Reckitt, Renault Group, Sanofi, Toyota, Unilever, Verizon, and Walmart. The pledge also has the support of several cancer charities and major research centers including Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York and Gustave Roussy in Paris.

The campaign is meant to be a wakeup call to companies of all sizes, Sadoun said. After all, 1 in 2 men and 1 in 3 women in the US, and 1 in 2 people in the UK, are at risk of developing cancer. Isn’t it time to end the stigma, so that employees don’t need to fear revealing when they or a loved one have been diagnosed? And shouldn’t employers be prepared to offer needed support?

“Cancer is such a particular thing,” Sadoun says. “It is so emotionally charged. It has such an impact on your life that you lose confidence. I’m the CEO of a 100,000-person company. I lost confidence, too. [I thought:] ‘How am I going to go through this? What will happen to my family? What will happen to my people?’”

“I have cancer”

The morning I was diagnosed, I had no idea how to tell anyone close to me, let alone my employer. I was 42, and afraid I was going to die.

Two minutes after I hung up with the radiologist, who’d delivered my diagnosis over the phone, my husband coincidentally called from his office. Flustered, I picked up, figuring I would make small talk and save my news for when he got home. But he knew immediately that something was wrong. I articulated the words for the first time ever: “I have cancer.”

What happened next shouldn’t be a surprise, given the prominence of work in our modern lives, and yet it still astonishes me when I think about it: I spent the rest of the morning reaching out not to my parents or sister or close friends, but to people I knew professionally, who could help me figure out what to do next. First up was Lauren, a work colleague. We weren’t close, but I liked her and respected her, and I knew she’d been treated for breast cancer a few years earlier.

“I have breast cancer,” I wrote to her on Slack. “Oh shit,” she replied. She left a meeting and called me. My first order of business, she let me know helpfully, was to find a surgeon.

But where would I find one? And how could I be sure they were good enough that I wouldn’t die from this, so that my then-10-year-old daughter wouldn’t lose her mother?

Suddenly I recalled a meeting from three years earlier, when a high-powered executive had visited the Quartz newsroom. She had mentioned, almost off-handedly, that she was a breast cancer survivor. I hadn’t written about it, or even asked her more. But in this moment, I knew I wanted the surgeon she’d had, because a) this executive was a smart, successful woman who would not mess around with cancer, and b) she was still alive.

I didn’t know how to reach her, so I contacted the PR agent who had set up the meeting. I barely knew her either, but I didn’t care. I needed answers.

The executive was traveling overseas, but the PR agent offered to put me in touch with two other connections straight away: her mother and a sibling, both of whom had been treated for breast cancer and could recommend surgeons in New York.

By the time I called my mother that night, I had an appointment scheduled with a well-regarded cancer surgeon and a sense of what would come next. I didn’t have to just say: “I have cancer.” I could tell her: “I have cancer, but here’s what we’re going to do.” There was at least some semblance of a plan.

The next morning, I sent my daughter off to school, got ready for work, and went to the office.

Practical policies for people with cancer

On Jan. 17, with the WEF as a partner, Sadoun was ready to present the Working With Cancer pledge to CEOs of 200 of the world’s biggest companies, at a meeting of the WEF’s International Business Council.

The pledge does not prescribe specific policies for employers. As for employees, “[i]t’s not telling people you have to be more open about it,” says Carla Serrano, the chief strategy officer of Publicis Groupe and an architect of the campaign. “It’s more about creating environments where people can be more open about it if they want to be.”

For transparency and perhaps inspiration, Publicis is sharing its own commitments. These include securing for one year the job and salary of any employee suffering from cancer, so that they can prioritize their health and leave work if necessary; training employee volunteers to provide peer support for colleagues diagnosed with cancer; and providing time off and other support to anyone caring for an immediate family member diagnosed with cancer.

Serrano says that many of the employers Publicis contacted about the pledge found, when they looked through their policies, that they already had at least a few helpful provisions in place for employees facing cancer or other grave illnesses. But often “they’re not visible, they’re not written in language people understand, they’re not accessible,” Serrano says. “Signing the pledge makes [the support] visible and accessible.”

She’s also encouraging signatories to publish the specific actions they take as part of the pledge. A handful of companies, including Walmart, have already agreed to do so, Serrano said. The hope is that, eventually, workplace policies for people with cancer will become at least as common as workplace policies for new parents.

“What we’re trying to address here is really to erase the stigma of cancer in the workplace,” Sadoun says. “When people hear about the fact they have cancer, first, of course they are afraid for their life, but very soon after, they are afraid for their job. As we have seen, half of them are scared to actually tell their employer they have cancer.”

How I told work, and the WEF, I had cancer

One of the weird things about being diagnosed with cancer is that, for all the tropes about fighting the disease, there are many hours in which you can do nothing about it. While I waited out the days until my first appointment with the surgeon, I threw myself into work even harder, just to compensate for the level of distraction in my head.

Once I saw the surgeon, I had a new calendar of events: an MRI, bloodwork, plastic surgery consultations, a scheduled mastectomy, and breast reconstruction. It was time to tell my boss what was happening, and what I needed in terms of time off. He was extremely concerned and supportive, just as I suspected he would be, and just as I understood he’d been with Lauren and another colleague who had undergone surgery for pancreatic cancer. He was getting far too used to hearing about cancer in the workplace. Maybe we all are.

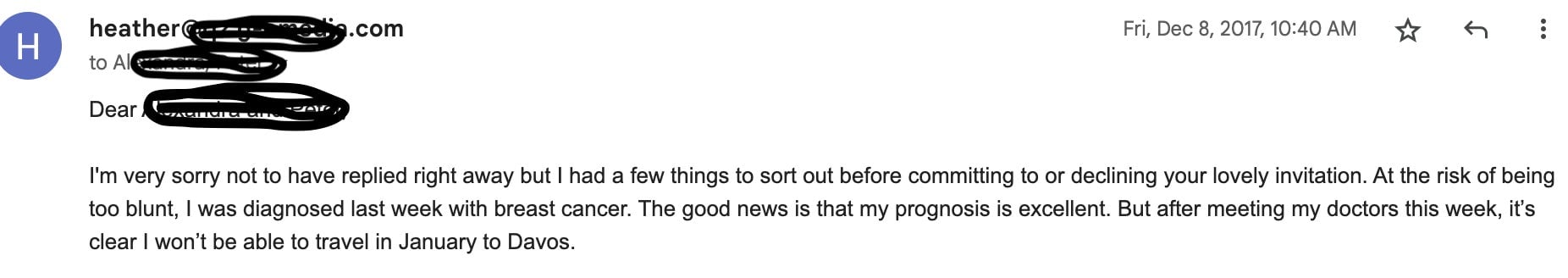

The next two people I alerted worked in the press office at the WEF. I had wanted so badly to accept their invitation a few days earlier to moderate a panel in Davos. But it was clear to me now that I would have to cancel the trip entirely. I must have reckoned that a longtime business journalist who’d finally landed a coveted invitation to Davos should have a good reason for backing out. And so, once again, I got over any awkwardness I felt about sharing private medical information with strangers and put it right there in the email:

The immediate reply from the press office was full of kindness and concern. And I’ve received a press pass to every WEF annual meeting since.

The power of telling people

A week after I told my boss, we had a plan in place for the team I managed. I told each of my direct reports that I had cancer, and then I started telling other colleagues. A helpful HR officer arranged my leave. A co-worker collected money to have meals sent to my family during my recovery; enough cash came in that the group decided to put half toward the food delivery and donate the other half to the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

I was grateful for the grace I received when I came back from leave. This was pre-covid, and I was encouraged to work from home whenever I needed. My first week or two back in the office, nobody minded when I cut my day short out of my sheer exhaustion. I did manage to avoid chemotherapy, which would have presented a whole new set of challenges in balancing health and work.

Eventually life at work returned to normal. In the years since, I’ve been given some cool new projects and a couple of promotions. I’ve never once felt that my illness, or my employer’s awareness of it, has held me back.

And now, here I am once again in Davos, where, in 2019, I attended a session featuring the executive I’d tried to reach the morning of my diagnosis. After the panel, we exchanged Hellos. Somehow I found the courage to tell her about that difficult day, and the role she’d unwittingly played in it. Her eyes widened, and we swapped notes on our treatment.

Then she said, “Stay here. I’ll be right back,” and she slipped behind the stage. A few minutes later, she came back with her bag and a business card, on which she wrote her mobile number. “So that you’re never not able to reach me if you ever need me again,” she explained, as she put the card in my hand.

Sharing all the way

Since being successfully treated, I’ve made myself available to several women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer—former colleagues, wives of colleagues, old classmates, friends of friends. But it wasn’t until the email about the Working With Cancer campaign arrived in my inbox that I considered sharing my experience so openly.

That’s the thing about wanting to erase stigmas: It compels us to tell our own stories, if only to normalize what we’ve been through. Five years on, I’m ready to do that, even if it means worrying how a future potential employer might react to finding out. If Working With Cancer is a success, I won’t have to worry for long.