China is slowing down—that much is clear. (Especially after this morning’s dismal trade report.)

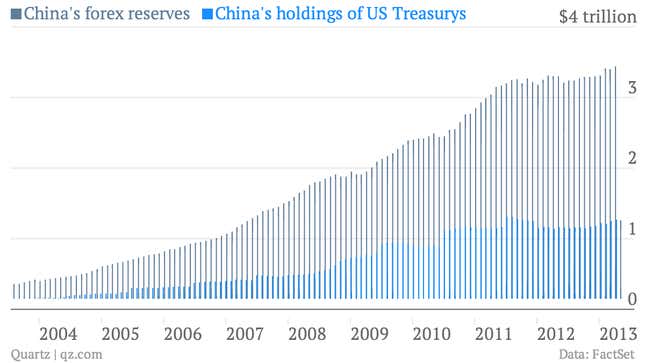

What isn’t, though, is what that means for everyone else. For those pondering America’s fortunes, China’s $1.26 trillion in holdings of Treasurys are a source of particular unease, for reasons articulated by economist Stephen Roach: ”Who will fund a seemingly chronic US saving shortfall—and on what terms—if America’s largest foreign creditor ceases doing so?”

Roach has a point. It’s unlikely any global player will emerge with the voracious appetite for US Treasurys that China has had. But that might be fine. Why? Because America might need to borrow less. And that means it will need fewer borrowers of its debt.

Let’s break this down.

China’s Treasury buying is an outgrowth of the government’s manipulation of its exchange rate. Simply put, China has pushed down the value of its currency, the yuan, as a matter of policy since the 1990s.

How? The People’s Bank of China—the central bank—prints fresh yuan and uses them to buy dollars at the exchange rate of its choosing. It then takes those dollars and stashes them in a safe place. That safe place has been the US Treasury market, pretty much the only market big and liquid enough to invest the volume of dollars China was amassing.

Why? A cheaper currency gives Chinese exporters an edge. That part’s well known, though. What’s less obvious is the effect of the Chinese government’s interest rate policy. By keeping bank deposit rates lower than the market rate—and often lower than inflation—Chinese banks could loan out funds to businesses at ludicrously cheap rates.

That was good for China’s export economy. Chinese businesses could sell cheaply and still have plenty of easy credit available to keep growing. At the same time, it seemed to be good for American consumers, who were able to buy these cheaper-than-they-should-have-been Chinese products.

But it was bad for Chinese households, since the government’s currency and interest rate policies crimped their wealth and purchasing power.

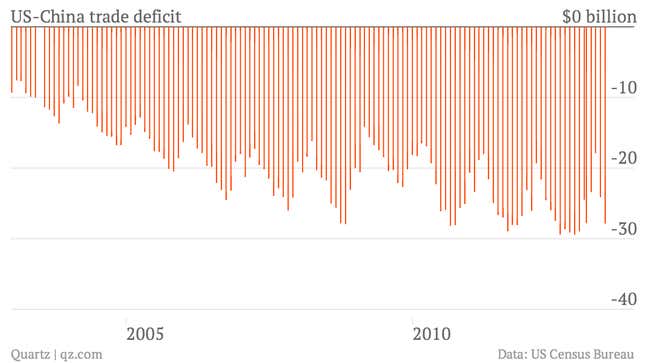

And it was bad for US manufacturers, both because they couldn’t compete with China’s subsidized export machine and because China’s policies choked off its demand for US imports. Between 2001 and 2011, the US-China trade deficit effectively killed 2.8 million US jobs, according to economist Robert E. Scott, including around half of US manufacturing jobs lost during that time.

In other words, the US was buying a lot more than it was selling. China’s share of the US trade deficit jumped from 20% in 1995 to 41% in the first five months of 2013.

And while it was buying cheap Chinese stuff, the US economy was losing business and jobs—and, therefore, tax revenue. In order to keep up consumption as revenue fell, the US had to borrow money, i.e. sell Treasury bonds.

And, what do you know? China’s mushrooming demand for US Treasurys pushed down interest rates, making it all the easier.

So in a sense, you can say that that China’s policy of keeping the yuan weak and its households poor enabled the US borrowing problem. (Pricey wars and lavish tax cuts exacerbated this.)

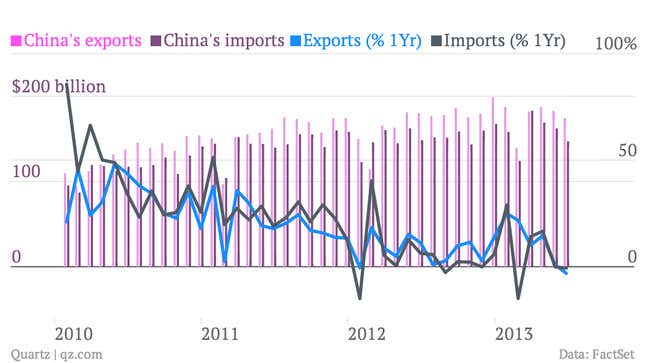

But here’s the thing: The effectiveness of China’s policies is waning. That’s evident in June’s lousy trade data. First off, it’s clear that the trusty old model is no longer working. China’s exports fell more than 3% in June, compared with the same month in 2012.

China could, of course, return to that model in a bid for stability. But that’s what it did just after the Lehman collapse. It started weakening the yuan and boosting lending to help juice exports. But now, excessive debt and overcapacity might that sort of stimulus push less effective.

Here’s a more interesting point, though. While China’s exports to the US rose only 1.5% in the first half of 2013, compared with the same period last year, imports of US goods jumped a whopping 15% (link in Chinese). That’s compared with a 10.4% increase in China’s overall exports, and only a 6.7% rise in imports.

That’s happening even as China’s economy is getting shakier. Of course, a “hard landing” of the Chinese economy would be bad for domestic consumption. And there’s a long way to go. Even as China’s US imports rose in the first half, compared with the previous year, they were still only 45% of the value of its exports to the US. Here’s a look at the size of that trade gap:

So what Stephen Roach was arguing is right. A slowing economy and falling exports means China won’t be buying up Treasurys anymore. But if that pickup in US imports keeps gradually righting the trade deficit, the US might not need to borrow so much either.