China has a chronic debt problem. And its soaring housing prices—Beijing’s were up 18.3% in July compared with last year—are getting fairly bubbly. That cocktail is mighty similar to what caused the United States financial crisis—so could a US-style sub-prime debacle happen in China?

Many say no. The government requires Chinese homebuyers to pay extremely high down payments—30-40% for first-time buyers. That means even if real estate prices did collapse, Chinese banks face less risk of their borrowers defaulting than US banks did. In other words, China might have a housing bubble, but it doesn’t have a credit bubble.

That might have been true a few years ago, but that’s changing fast.

In 2013’s first half, banks issued 179% more mortgage loans than the previous year

For one thing, even with down payments still burdensome, sky-high prices are sending China’s mortgage lending off the charts. Outstanding mortgage loans hit $1.5 trillion (link in Chinese; pdf, p.3) at the end of June, an increase of 21% on H1 2012. More than one-tenth of that is new mortgages, which hit a record $157 billion in the first half of 2013, up a whopping 179% on H1 2012 (link in Chinese; pdf, p.3).

Some banks are already hitting their annual mortgage quotas

The mortgage lending craze has gotten ahead of some banks. Some Guangzhou branches have had to suspend mortgages because they’ve already hit their 2013 quota, as Sinocism flags. Banks in a Beijing suburb called Yanjiao hit their limits (link in Chinese) a few weeks ago.

“Creative” lending is on the rise

But official mortgage lending data doesn’t capture the entire debt picture for China’s new homeowners. Excessively high housing prices are making it hard for most to cough up the required 30-40% down payment. As a result, banks becoming “very creative in helping consumers” make mortgage down payments, says Junheng Li, head of research at JL Warren Capital.

One increasingly common scheme (link in Chinese) involves an informal version of “reverse mortgages,” which aren’t legal in China. When a prospective buyer can’t pay the down payment, banks allow the buyer’s parents to take out a loan using their home as collateral in order to generate the cash.

Because these loans aren’t technically allowed, they sometimes “take the form of auto or other types of discretionary consumer loans,” says Li, whose forthcoming book, Tiger Woman on Wall Street, argues that China suffers from a housing bubble. This has been going on for a while, she says, particularly in big cities.

In other words, banks are exposing themselves to more risk than their balance sheets reflect. In using improvised reverse mortgages, banks are lending to a set of people deemed too risky by Chinese regulators. That’s pretty much the definition of ”sub-prime lending.”

Some scary fundamentals

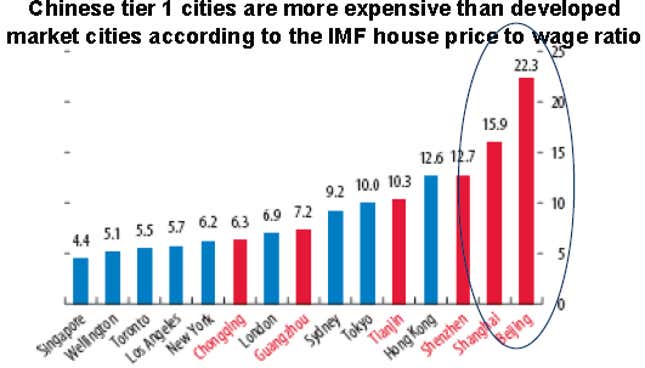

That would explain how people are coming up with the cash to buy homes even as prices push higher than ever. A 1,000-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment in Beijing now costs around $408,500. That might not sound crazy, considering housing prices in some American cities, but consider that people in China earn far less than those in the US. Here’s a look at how housing price-to-income ratios in various parts of China stack up against cities globally:

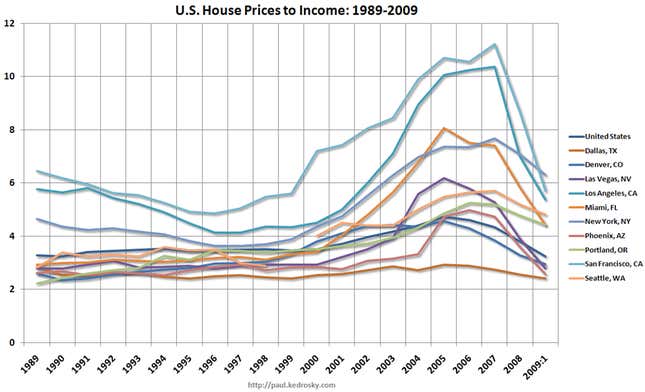

And the US, pre-crisis:

In plain English, that means that it would take the median buyer about 22.3 years worth of wages to pay off his Beijing apartment. Prior to the US housing bust, the frothiest market—San Francisco—required around 11 years worth of income.

This will create a whole new wave of “housing slaves“—the slang term for new homebuyers who have to use around 70% of their salaries to pay the mortgages—as well as “housing slave” parents. The economic slowdown that looks increasingly inevitable will necessarily entail layoffs, which will make some of these debts bad.

What’s more, the majority of home loans in China have variable interest rates (pdf, p.13). As the government shifts from monetary to fiscal stimulus and the slowing economy causes businesses to default, cash is starting to dry up. Unless the government intervenes, that will cause interest rates to rise for homeowners—the very thing that triggered the US housing collapse. This isn’t just theoretical; in the wake of June’s credit crunch, some banks have already raised mortgage rates by 10% (link in Chinese).

Still not a US-style credit bubble… yet

And yet, all said, China is still in better shape than the US was pre-crisis. The $1.5 trillion in outstanding mortgages on the books of Chinese banks is far short of the $10.6 trillion loaned out by US banks in mid-2008. Chinese lenders also have higher capital requirements than US banks—enough capital to weather a 40% drop in home values, they say. Plus, Chinese banks also don’t trade in mortgage-backed securities.

But a 179% rise in mortgages and shifty lending practices suggest that banks are hitting the accelerator on consumer lending, even as conditions get riskier. That means China may be adding a credit bubble to its housing bubble sooner than it realizes.