Currency traders and foreign investors may be fretting over their losing short-term bets on India’s troubled currency, but India itself has much bigger troubles in store if the recent nosedive of the rupee—it fell 4% today against the US dollar, and is down 27% over the last six months—continues.

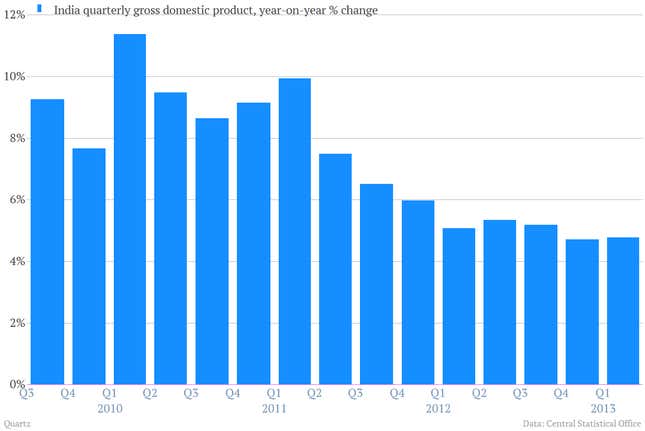

Once a star performer among emerging markets, the country is likely to kiss a return to rapid growth goodbye if the rupee continues to crater. (Some 60% of emerging markets studied in this IMF paper shrank after sharp devaluation in their currency.) That’s especially worrisome for a country like India, where growth has already slowed significantly in recent years. In the year ended in March, the country grew at its slowest pace in a decade.

Why?

Higher interest rates

The Reserve Bank of India took steps back in July to try to shore up the rupee. It used the traditional first line defense of central banks trying to defend a currency: raising interest rates by tightening the money supply.

The severe move was intended to slow the economy, which in theory helps beat back inflation and support the currency.

But the plan looks like it will just slow the economy without supporting the currency. BNP Paribas today cited higher interest rates as one of the reasons that it sharply cut its growth forecast for India for the 2013-14 fiscal year, to 3.7% from 5.2%.

Meanwhile, conflicting signals sent by the Reserve Bank have continued to drive down the currency’s value. If the falling rupee continues to push up inflation, the central bank won’t have the option of loosening interest rates to help buoy growth. That’s because cutting rates—the traditional way of helping the economy—will only worsen inflation. As a result, the only hope for improving India’s growth prospects will come when the rupee finds a bottom.

A tough, but perhaps needed, economic adjustment awaits India.

Indian authorities haven’t been willing to go beyond raising interest rates to defend the rupee on the open market, which would require them to burn up precious foreign exchange reserves to buy rupees. Thus, the currency is likely to keep tumbling, driving up inflation and tying the Reserve Bank’s hands on boosting the economy.

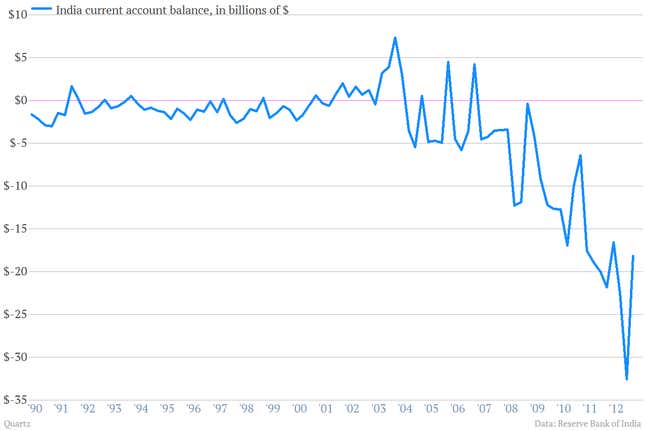

That could be painful. But in a best-case scenario it could get to the heart of India’s currency woes: that India buys more from foreigners than it sells to them, resulting in a very large current account deficit. Check it out.

Ideally, to solve this problem, the Indian economy would slow enough that imports would fall due to weak demand, which would shrink the current account gap. The weak rupee would in theory make Indian exports a bit cheaper for foreign buyers, bringing more cash into the country. And bottom-fishing global investors would see India as a bargain and reinvest.

But that scenario comes with high costs: falling wealth, weaker economic growth and higher unemployment. Either route to recovery—burning up foreign exchange reserves or allowing the rupee to keep falling—will cause serious pain.