The next how-many-ever billion is a popular phrase in technology at the moment, given its most visible outing by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who recently told the world he wants to bring the remaining 5 billion of the earth’s population online. Thinking in tech circles dictates that smartphones will do the trick; they’re cheaper and easier to use than computers. But a report about Myanmar’s nascent mobile phone market from research firm IDC shows that even when starting from an all but clean slate—the country of 60 million had fewer than 3 million mobile phone subscribers last year—not everyone wants to jump online. In fact, it takes years for smartphones—and therefore mobile internet—to take root even at a time of explosive growth.

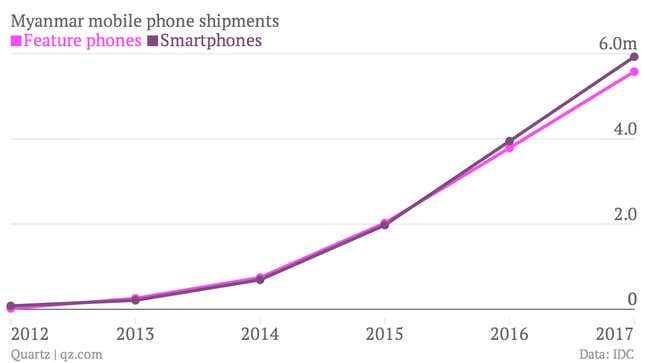

The chart above shows mobile phone shipments with data from a recent IDC report. According to IDC’s figures, it won’t be until 2016—a full three years after Myanmar opened up its mobile sector—that more smartphones will be sold in the country than simpler, feature phones. There are three main reasons for this: First, Myanmar remains a poor country and even the cheapest smartphones cannot compare with basic voice-and-text models that go for less than $20 new, and even less second-hand. The second is related: Network coverage remains patchy, wifi hotspots scarce (though growing) and data plans expensive.

But the third reason is perhaps most pertinent: Like any other form of communication technology, smartphones benefit from network effects and there seems little point in having one if your friends don’t have them. Who will you email, send WeChat messages to or tweet at? A 2011 study by Facebook found that “84% of all connections are between users in the same country.” In a country with less than 1% of the population online, it’s going to take quite a while for network effects to kick in.

Efforts like Facebook’s, which will reduce bandwidth consumption, improving telecom infrastructure and creating market mechanisms such as mobile payments will help, as will a push from the government which wants to grow mobile penetration from 5% now to 75% by 2016. But Myanmar shows that even with incentives and encouragement, it will be a slow, hard and unglamorous climb before Silicon Valley’s utopians get their dream of a fully-connected world.