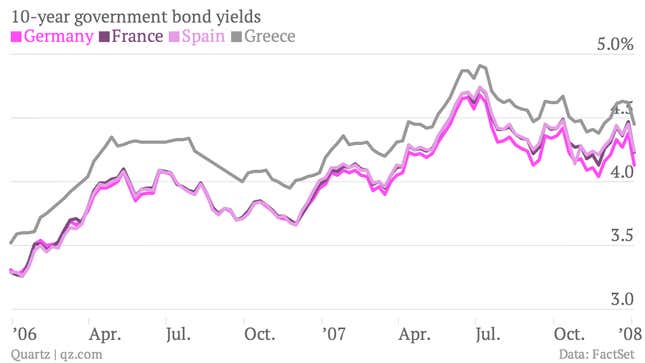

Those were the days. Before the global financial crisis morphed into the euro debt crisis, investors saw all euro-zone government bonds more as more or less the same. Yields on German, Spanish and even Greek bonds traded within a narrow range. (Yields move in the opposite direction to prices.)

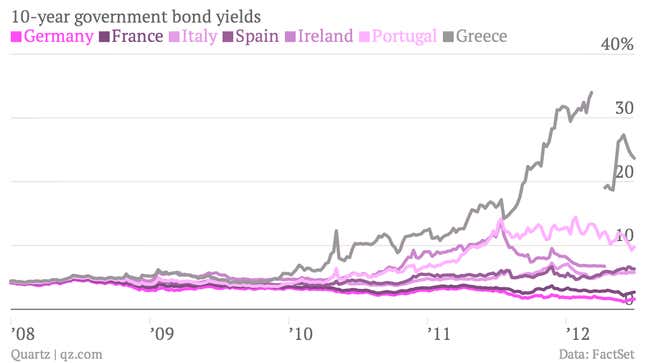

We all know what happened next. Financial firms collapsed, roping governments into costly rescue efforts. Jittery investors dumped risky assets, pushing up rates for a wide range of borrowers, including the shakier sovereigns. A chart of euro government yields around this time shows a violent separation of the “periphery” from the “core.”

After a series of international bailouts for the biggest basket cases, it seemed like the euro zone was as likely to break apart as stay together. That is, until European Central Bank president Mario Draghi said he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro in mid-2012. Borrowing costs for the hardest-hit countries duly drifted lower, although spreads remained wider than pre-crisis levels.

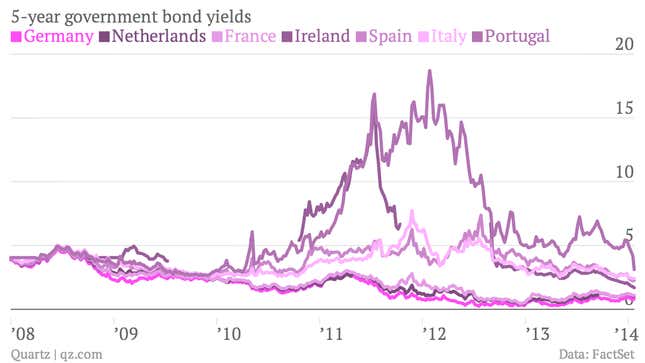

And then, at the turn of this year, investors went on a euro-zone bond-buying spree. Spain set a record yesterday for the most orders ever submitted for a European government debt sale, with some €40 billion ($54.2 billion) in orders chasing a €10 billion, 10-year issue. The last time the 10-year yield was this low, in 2006, Spain’s unemployment rate was 8.5% (it is now 26.7%) and it ran a budget surplus of 2.4% of GDP (it is a deficit of around 7% today).

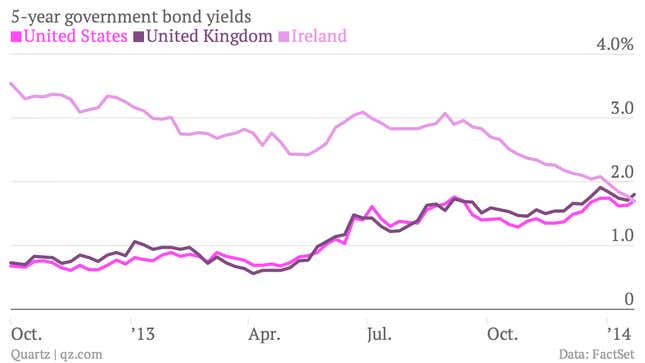

The star performer, though, is Ireland. Only a month after exiting its bailout, the country has had no trouble issuing new debt. In fact, Ireland’s five-year borrowing cost recently dipped below its American and British equivalents, to the lowest level recorded in the republic’s 92-year history. And this is a country where the debt-to-GDP ratio is a heady 125%, and nearly a fifth of all mortgages are behind on payments.

What gives? In some sense, Ireland is being “disproportionately rewarded” for its recent strides, according to Brian Lucey, a professor at the business school of Trinity College Dublin. Indeed, compared with fellow bailout recipients like Greece, Ireland has been a model student. And if Draghi is serious about his “whatever it takes” pledge, in theory there is no longer a risk of default on euro zone government bonds, wherever they come from. “One could legitimately ask why there is any distinction,” Lucey says.

Taking a longer view of bond-market trends, yields are clearly converging again—Ireland is leading a pack of countries downwards while Germany and other “core” countries’ yields creep up to meet them.

Will the remaining gaps eventually all but disappear, like before the financial crisis? The investors aggressively bidding down the yields of Irish, Spanish and other once-radioactive bonds seem to think so. Some may find it puzzling that countries so recently in intensive care, like Ireland and Spain, are now seeing borrowing costs tumble to historic lows. But others are asking what took so long, and why yields haven’t fallen even further.