The bailout era is about to end in Ireland.

On Sunday, the country is set to become the first euro-zone country to exit a bailout that it was forced to take during the the European financial crisis. That means Ireland will have drawn down all of the €67.5 billion ($93 billion) credit line it received from the “troika”—the European Commission, IMF and the European Central Bank—to pay its bills in 2010. After Sunday, it will look to fund itself by borrowing in the bond markets. (It also has more than €20 billion in cash reserves on hand to pay any other items that may pop up.)

Greece, Portugal and Cyprus continue to rely on cash supplied by the troika. In exchange, they’ve agreed to undertake painful structural reforms, such as tax increases and spending cuts, that have weighed heavily on economic growth. Ireland will now be free of such conditions (though it still has to pay back the troika’s loans: their average maturity is 12.5 years.)

So what’s the state of the Irish economy as it prepares to try to stand on its own two feet once again?

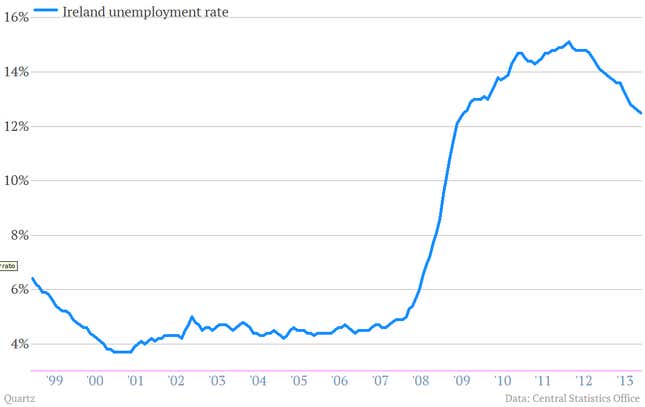

Unemployment is high, but moving in the right direction.

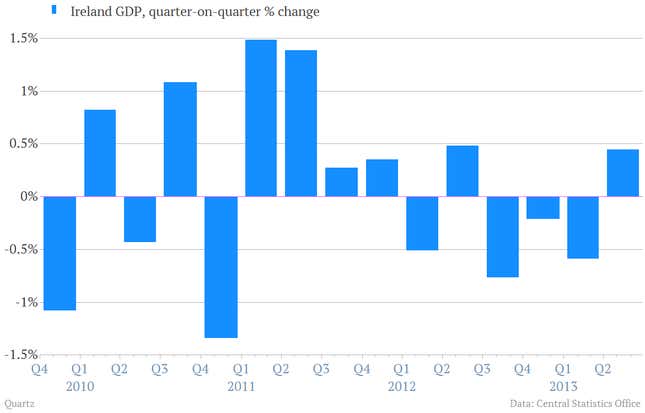

The economy is growing again, but only just.

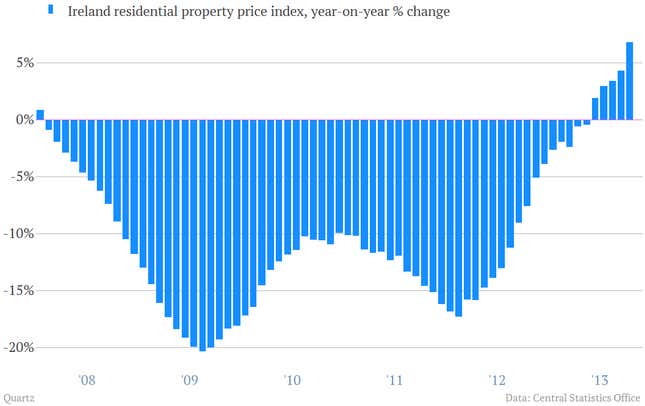

On the other hand, after the giant real estate bust, home prices have started to move up again.

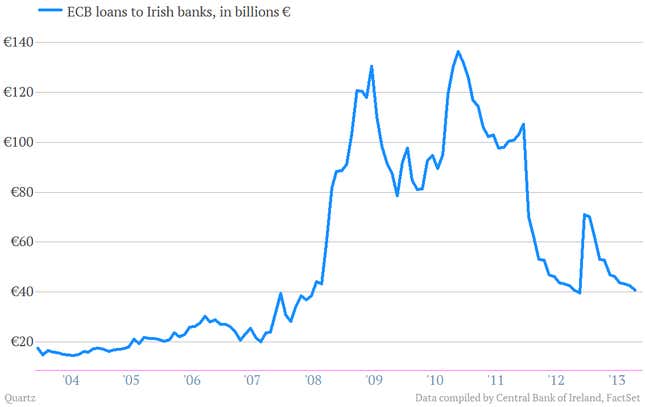

Irish banks continue to lean on the ECB, but not as heavily as they used to.

The mood of Irish consumers has improved markedly of late.

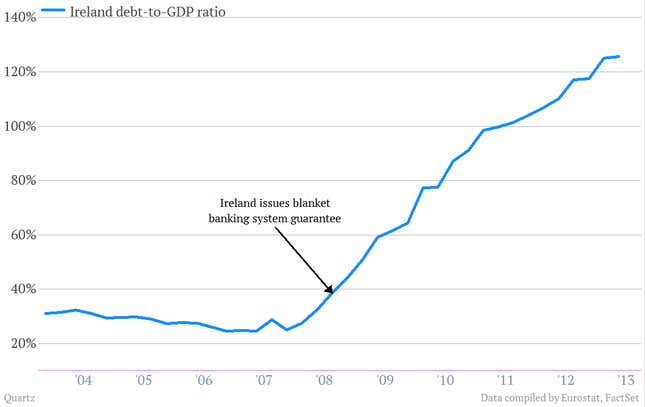

And while the the Irish government is now laboring under a far worse load of debt than it was before the crisis…

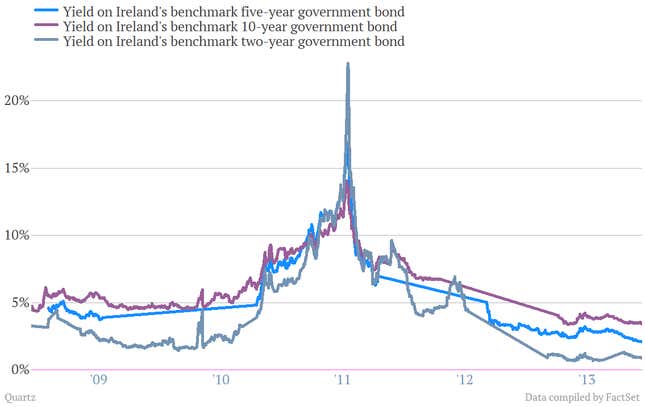

…Ireland’s borrowing costs have fallen quite sharply from the worst of the panic, when it became too expensive to borrow in the markets, forcing the government to seek a bailout.

On that last chart, it’s important to note that a lot of the confidence the market gained in Ireland had to do with the fact that it was solidly backed by the troika. In an attempt to demonstrate its independence, Ireland has talked up the fact that it plans to exit the bailout without a large credit line from the troika. But in reality, the markets recognize that there is an implicit level of support for Ireland from the Troika, which will make them much more likely to give Ireland the benefit of the doubt when it is peddling its bonds.