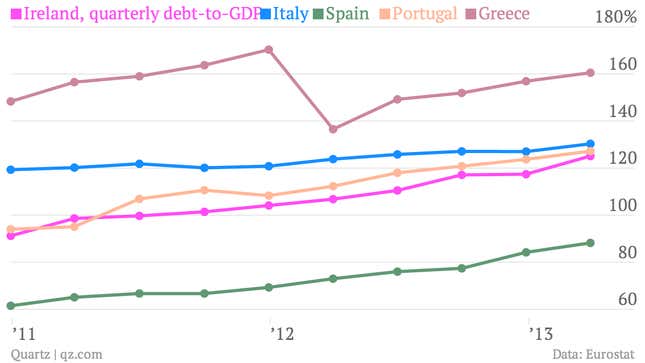

We’ll say it again. If the goal of today’s European powers is to reduce the debt loads of the troubled countries that set off the European debt crisis over the last three years, it just isn’t working.

The latest official quarterly debt-to-GDP numbers couldn’t be any clearer.

Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio hit 130% during the first quarter of 2013, a new record. Ireland’s continued to escalate, touching 125% at the end of March. Greece remains a basket case. Even after having defaulted on its debt twice over the last few years—which sharply cut the debt outstanding—it posted the highest overall debt-to-GDP ratio, 160%. But it also posted the highest quarter-over-quarter rise in the measure. Look for yourself.

The situation in Europe is an example of what British economist John Maynard Keynes called the “paradox of thrift.” While it is considered prudent for heavily indebted individuals and families to cut down on spending, the same process isn’t always wise for entire economies. That’s because unlike with an individual or family, in an economy spending on consumption and investment is needed to spur growth. One person’s spending becomes another person’s income. And if everyone tries to cut spending and boost savings at once, it means that the economy as a whole slows.

The result is lower tax revenues, higher spending on social welfare programs, and zero progress on cutting debt.

Also, steep budget cuts can lead to hardship and suffering—and social unrest. Austerity at all costs in Europe has led unemployment in Spain and Greece to top 25%. Keynes would be shaking his head.