Global investors have suddenly remembered that emerging markets have a rich, recent history of florid financial crises.

The cracks are starting to emerge everywhere: wobbly “wealth management products” in China, the Turkish lira’s tumble, the selloff in Brazilian bond markets and last summer’s mini-rupee crisis.

So are we about to see a replay of the Brazil 1999, Turkey 2001, Russia 1998, the Thai baht bust of 1997, Mexico 1982 or Mexico 1994?

Not exactly. Yes, emerging markets have absorbed a tsunami of investor cash in recent years. And yes, historically, when inflows of investor cash start reversing course, problems tend to present themselves.

But by and large, the big problems this time around will differ from what we saw in the late 1990s.

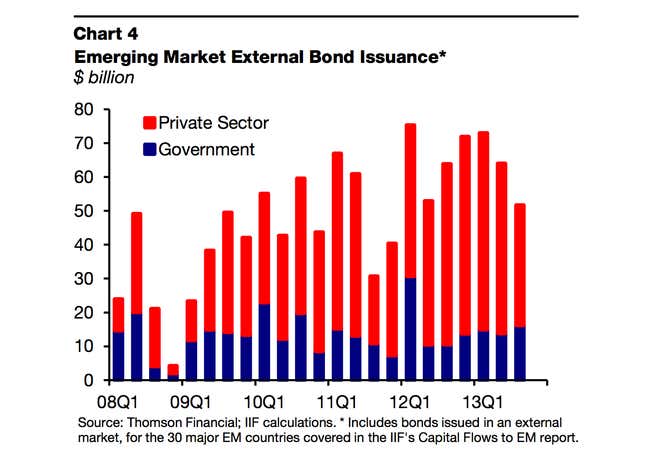

For one thing, many EM countries moved to flexible exchange rates after the unpleasantness of the late-1990s experience, which at least in theory is supposed to insulate these economies from major shocks. (Although it doesn’t help them avoid distress altogether.) And for another thing, instead of government bonds, the immediate carnage will likely show up in corporate debt. Check out this chart, from global banking group the Institute of International Finance. It shows that the vast majority of bonds issued by emerging markets have been borrowings by private entities, rather than governments.

Let’s talk Turkey, for example.

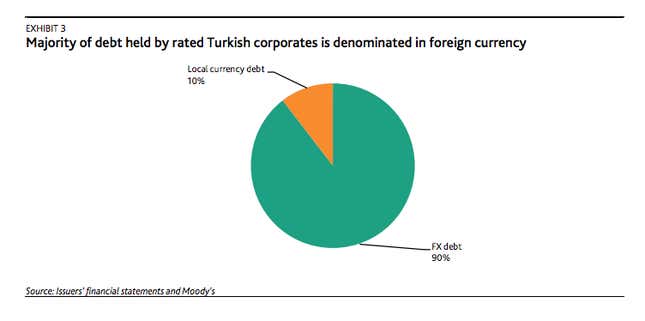

Over the last few years, Turkish corporations did a lot of borrowing in foreign currencies. Why? Because it was cheaper. As a result, the structure of Turkish corporate liabilities looks something like this, according to Moody’s.

Borrowing cheaply in foreign currencies may have seemed a good idea at the time. But a weakening Turkish lira–and it’s been weakening a lot—makes those debts much more difficult to pay back. (The currency is down about 4.4% against the US dollar this year alone. Over the last three months it’s down by about 11%.)

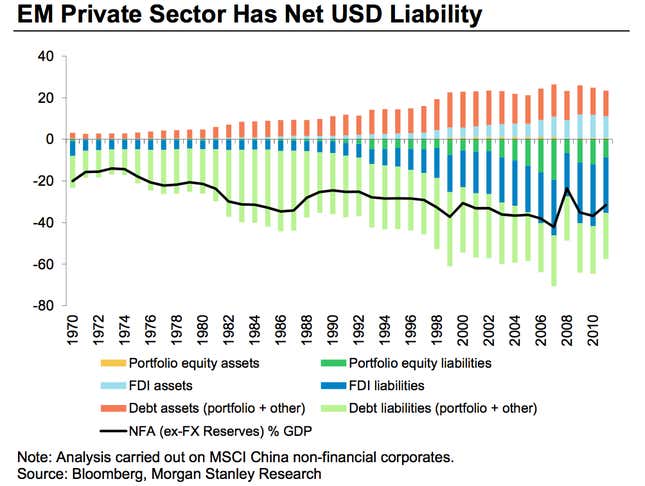

Here’s another look at the same trend, from Morgan Stanley analysts. The takeaway: The emerging market private sector owes a lot of dollar-denominated payments to investors.

Emerging market central banks have been trying to prop up their currencies by raising interest rates, which could work. But those higher interest rates will also make it tough for emerging market corporates, for instance, by acting as a drag on economic growth. (And economic growth in a lot of these countries is already arriving somewhat below overly enthusiastic expectations.)

Problems in the corporate bond market could also scare investors away from government debt purchases in emerging markets. That’s because slowing growth would hurt tax revenues and potentially demand more fiscal spending, both of which would hurt the national balance sheet.

Governments might even be on the hook for the bad debts of certain corporate entities. (Example: The US government nationalized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac during the US financial crisis.)

Add those to the pile of worries investors have about the fate of the global economy.