The internet is a confusing place, and not just because of all the memes.

Right now, many of the people who make the internet run for you are arguing about how it should work. The deals they are working out and their attempts to influence government regulators will affect how fast your internet access is and how much you pay for it.

That fight came into better view last month when Netflix, the video streaming company, agreed to pay broadband giant Comcast to secure delivery of higher-quality video streams. Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, complained yesterday about Comcast “extracting a toll,” while Comcast cast it as “an amicable, market-based solution.” You deserve a better idea of what they are talking about.

For most of us, the internet is what you’re looking at right now—what you see on your web browser. But the internet itself is comprised of the fiber optic cables, the servers, the proverbial series of tubes, all owned by the companies that built it. The content we access online is stored on servers and transmitted through networks owned by lots of different groups, but the magic of the internet protocol lets it all function as the integrated experience we know and, from time to time, love.

The last mile first

Start at the top: If you’ve heard about net neutrality—the idea that internet service providers, or ISPs, shouldn’t privilege one kind of content coming through your connection over another—you’re talking about “last mile” issues.

That’s where policymakers have focused their attention, in part because it’s easy to measure what kind of service an individual is getting from their ISP to see if it is discriminating against certain content. But things change, and a growing series of business relationships that come before the last mile might make the net neutrality debate obsolete: The internet problem slowing down your Netflix, video chat, downloading, or web-browsing might not be in the last mile. It might be the result of a dispute further up the line.

Or it might not. At the moment, there’s simply no way to know.

“These issues have always been bubbling and brewing and now we’re starting to realize that we need to know about what’s happening here,” April Glaser of the Electronic Frontier Foundation says. “Until we get some transparency into how companies peer, we don’t have a good portrait of the network neutrality debate.”

What the internet is

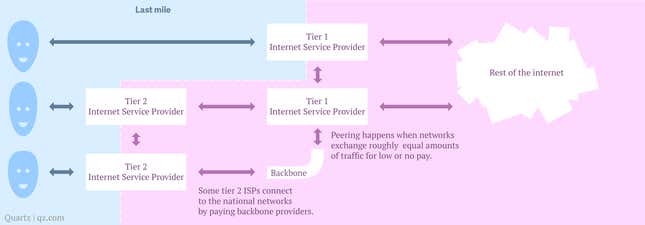

What happens before the last mile? Before internet traffic gets to your house, it goes through your ISP, which might be a local or regional network (a tier 2 ISP) or it might be an ISP with its own large-scale national or global network (a tier 1 ISP). There are also companies that are just large-scale networks, called backbones, which connect with other large businesses but don’t interact with retail customers.

All these different kinds of companies work together to make the internet, and at one point, they did so for free—or rather, for access to users. ISPs would share traffic, a process called settlement-free peering, to increase the reach of both networks. They were worked out informally by engineers—”over drinks at networking conferences,” says an anonymous former network engineer. In cases where networks weren’t peers, the smaller network would pay for access to the larger one, a process called paid peering.

For example: Time Warner Cable and Comcast, which started out as cable TV providers, relied on peering agreements with larger networks, like those managed by AT&T and Verizon or backbone providers like Cogent or Level 3, to give their customers what they paid for: access to the entire internet.

But now, as web traffic grows and it becomes cheaper to build speedy long-distance networks, those relationships have changed. Today, more money is changing hands. A company that wants to make money sending people data on the internet—Netflix, Google, or Amazon—takes up a lot more bandwidth than such content providers ever have before, and that is putting pressure on the peering system.

In the facilities where these networks actually connect, there’s a growing need for more ports, like the one below, to handle the growing traffic traveling among ISPs, backbones, and content providers.

But the question of who will pay to install these ports and manage the additional traffic is at the crux of this story.

How to be a bandwidth hog

There are three ways for companies like these to get their traffic out to the internet.

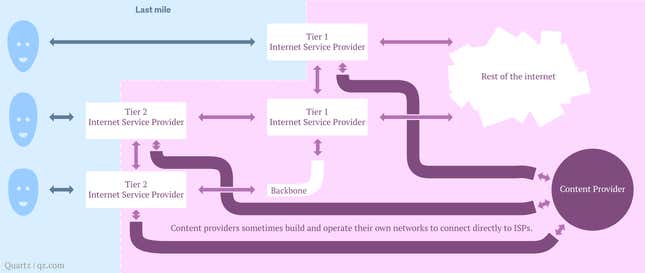

With cheaper fiber optic cables and servers, some of the largest companies simply build their own proprietary backbone networks, laying fiber optic wires on a national or global scale.

Google is one of these: It has its own peering policies for exchanging data with other large networks and ISPs, and because of this independence, its position on net neutrality has changed over the years. That’s also why you don’t hear as much about YouTube traffic disputes as you do about Netflix, even though the two services pushing out comparable quantities of data.

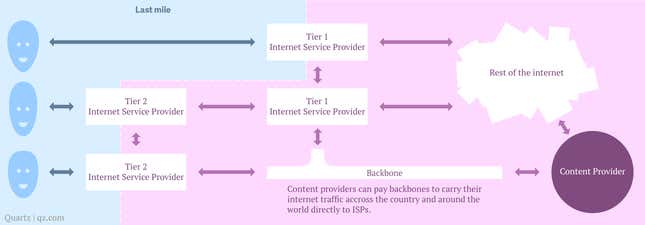

Or your company can pay for transit, which essentially means paying to use someone else’s backbone network to move your data around.

Those services manage the own peering relationships with major ISPs. Netflix, for instance, has paid the backbone company Level 3 to stream its movies around the country.

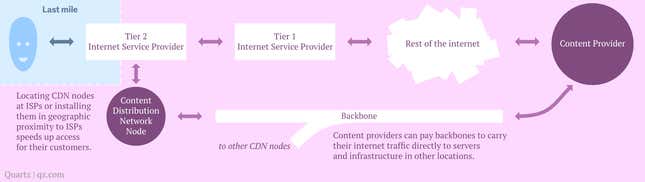

The final option is to build or use a content distribution network, or CDN. Data delivery speed is significantly determined by geographical proximity, so companies prefer to store their content near their customers at “nodes” in or near ISPs.

Amazon Web Services is, among other things, a big content distribution network. Hosting your website there, as many start-ups do, ensures that your data is available everywhere. You can also build your own CDN: Netflix, for instance, is working with ISPs to install its own servers on their networks to save money on transit and deliver content to its users more quickly.

Ready to be even more confused? Most big internet companies that don’t have their own backbones use several of these techniques—paying multiple transit companies, hiring CDNs and building their own. And many transit companies also offer their own CDN services.

Why you should care

These decisions affect the speed of your internet service, and how much you pay for it.

Let’s return to the question of who pays for the ports. In 2010, Comcast got into a dispute with Level 3, a backbone company that Netflix had paid for data transit—delivering its streaming movies to the big internet. As more people used the service, Comcast and Level 3 had to deal with more traffic than expected under their original agreement. More ports were needed, and from Comcast’s point of view, more money, too. The dispute was resolved last summer, and it resulted in one of the better press releases in history:

BROOMFIELD, Colo., July 16, 2013 – Level 3 and Comcast have resolved their prior interconnect dispute on mutually satisfactory terms. Details will not be released.

That’s typical of these arrangements, which are rarely announced publicly and often involve non-disclosure agreements. Verizon has a similar, on-going dispute with Cogent, another transit company. Verizon wants Cogent to pay up because it is sending so much traffic to Verizon’s network, a move Cogent’s CEO characterizes as practically extortionate. In the meantime, Netflix speeds are lagging on Verizon network—and critics say that’s because of brinksmanship around the negotiations.

What Netflix did last month was essentially cut out the middle-man: Comcast still felt that the amount of streaming video coming from Netflix’s transit providers exceeded their agreement, and rather than haggle with them about peering, it reportedly reached an agreement for Netflix to (reluctantly) pay for the infrastructure to plug directly into Comcast’s network. Since then, Comcast users have seen Netflix quality improve—and backbone providers have re-doubled their ire at ISPs.

Users versus content

You’ll hear people say that debates over transit and peering have nothing to do with net neutrality, and in a sense, they are right: Net neutrality is a last-mile issue. But at the same time, these middle-mile deals affect the consumer internet experience, which is why there is a good argument that the back room deals make net neutrality regulations obsolete—and why people like Netflix’s CEO are trying to define “strong net neutrality” to include peering decisions.

What we’re seeing is the growing power of ISPs. As long-haul networks get cheaper, access to users becomes more valuable, and creates more leverage over content providers, what you might call a “terminating access monopoly.” While the largest companies are simply building their own networks or making direct deals in the face of this asymmetry, there is worry that new services will not have the power to make those kinds of deals or build their own networks, leaving them disadvantaged compared to their older competitors and the ISP.

“Anyone can develop tools that became large disruptive services,” Sarah Morris, a tech policy counsel at the New America Foundation, says. “That’s the reason the internet has evolved the way it has, led to the growth of companies like Google and Netflix, and supported all sorts of interesting things like Wikipedia.”

The counter-argument is that the market works: If people want the services, they’ll demand their ISP carry them. The problem there is transparency: If customers don’t know where the conflict is before the last mile, they don’t know whom to blame. Right now, it’s largely impossible to tell whether your ISP, the content provider, or a third party out in the internet is slowing down a service. That’s why much of the policy debate around peering is focused on understanding it, not proposing ideas. Open internet advocates are hopeful that the FCC will be able to use its authority to publicly map networks and identify the cause of disputes.

The other part of that challenge, of course, is that most people don’t have much choice in their ISP, and if the proposed merger between the top two providers of wired broadband,Time Warner Cable and Comcast, goes through, they’ll have even less.