The medieval city of Salisbury in England’s southwest is dripping with history. Its majestic cathedral, completed in 1258, contains what is believed to be the world’s oldest functioning clock and one of just four original copies of the Magna Carta. The prehistoric ruins of Stonehenge are just eight miles to the north.

But this ancient town is also home to a very modern corporation. In a complex on the outskirts of the city are the headquarters of GW Pharmaceuticals, which is no ordinary biotech business. It’s probably the world’s most valuable cannabis company.

GW Pharmaceuticals doesn’t sell weed, per se, but rather prescription cannabinoid medicines. The company, which has garnered some media attention, is listed on both the London Stock Exchange and on the Nasdaq. Its US listing has surged by 75% in 2014, and by 713% since last May, pushing its market value to above $1 billion. All this for a company that generated just $44 million in sales last year. This optimistic valuation is partly a function of the seemingly inexorable shift toward the legalization of cannabis in the United States.

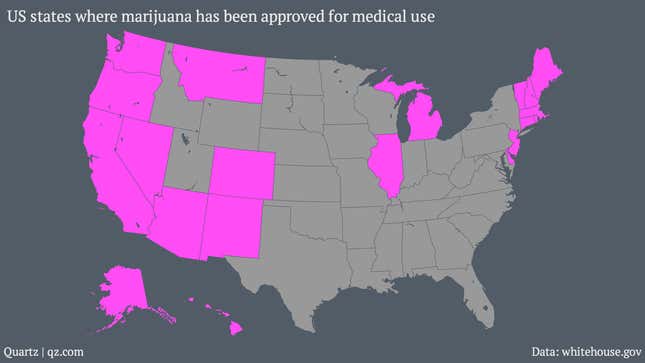

This year so far, two US states—Colorado and Washington—effectively declared cannabis legal. The drug has also been approved for medicinal purposes in another 18 states plus Washington DC, which together have a cumulative population of about 117 million people, or more than a third of all Americans. At least 14 other states, including Maryland and Florida, are considering laws that would approve marijuana for medical use this year, the New York Times reported.

While this is delighting potheads and upsetting some drug advocacy groups, it is also creating a unique headache for the country’s pharmaceutical regulator, the Food and Drug Administration, which has never approved marijuana as a legitimate treatment. Part of the reason for the surge in GW Pharmaceuticals’ share price this year is the belief among some investors that the company could provide the FDA with an elegant way out of this predicament.

Last year, GW’s cannabinoid spray, Sativex, which is used to treat spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis, was approved for sale in eleven European countries. It is currently in the third and final phase of testing by the FDA in separate trials for multiple sclerosis treatment, as well as for use as relief from cancer pain. If it gets through this Phase III testing, it could become the first FDA-approved cannabis-based product to hit the market in the US, and provide an alternative way to consume weed for medical purposes besides smoking or eating it. (There are other products that contain synthetic versions of cannabis chemicals, but Sativex is the only one to contain actual extracts from marijuana plants.)

“The FDA is in a bit of a bind because some states are approving medicinal marijuana, and this is an absolute nightmare because it’s very difficult to control the manufacturing of it,” Samir Devani, a biotech analyst at WG Partners in London tells Quartz. “You can imagine that the FDA … [is saying] hang on a minute, this might be a saving grace for us. If there’s an FDA-approved product on the market, then why do you need medicinal cannabis?”

Big business

A study by RAND Corporation estimates that Americans consumed $40.6 billion worth of marijuana in 2010, an increase of 30% over a decade earlier. A separate study by IBIS World estimated the US medicinal marijuana industry to be worth $2 billion last year, with annualized growth of 13.8% from 2008. Whichever way you look at it, the marijuana industry is huge and growing rapidly. Now, as it becomes increasingly legally acceptable, its entrepreneurs are moving out of the shadows of the underworld and into mainstream commerce. For example, this week, the Wall Street Journal profiled (paywall) Justin Hartfield, probably America’s most prominent legal weed mogul. Hartfield runs weedmaps.com, a sort of Yelp for legal marijuana dispensaries, which reportedly made $25 million last year. He also recently launched Ghost Capital, a pot-focused venture capital fund.

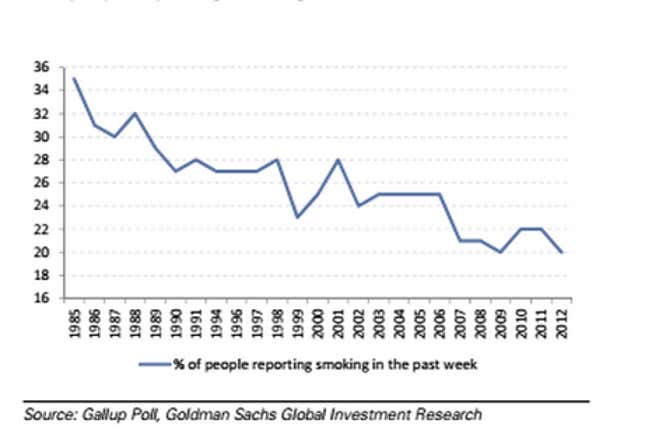

For ordinary investors, there are limited ways to bet on this shift in the consumer economy. The obvious industry to capitalize on the creeping legalization of marijuana is big tobacco. Cigarette sales have been steadily declining, and marijuana (alongside tobacco-less products like e-cigarettes) would be an obvious way to pick up the slack.

Yet despite satirical reports about a Marlboro marijuana cigarette, the industry has given no public indication that it will start marketing joints. The terms “marijuana” or “cannabis” do not show up once in a search of the transcripts of earnings and conference calls for the major cigarette makers since the beginning of last year. Investment bank tobacco analysts contacted by Quartz declined to comment on the issue. “Marijuana remains illegal under federal law, and Altria’s companies have no plans to sell marijuana-based products,” a spokesman for the tobacco giant that owns Marlboro and other brands said earlier this year.

There are a string of smaller, over-the-counter listed companies actively promoting themselves as marijuana companies. They include Growlife, which currently has a market value of about $503 million, Advanced Cannabis Solutions, worth about $570 million, and MedBox, valued at $443 million. Since I last warned about the dangers of investing in these companies, Growife and Advanced Cannabis Solutions have both increased in value. Yet they remain highly volatile stocks and don’t carry the prestige of a major exchange listing.

Which brings us back to GW Pharmaceuticals. The company has been around since 1998, floated on the London Stock Exchange in 2001, and battled investor skepticism for about the next 10 years. Now, with interest in marijuana at possibly unprecedented levels, it is benefitting from the paucity of legitimate weed investment options.

At a secret location somewhere in the south of England, GW has a marijuana-growing facility that produces 200 tons of raw material and about 20 tons of actual pot each year. (The facility is reportedly guarded around the clock, and each plant is genetically fingerprinted to enable tracking, should anything be stolen.) From these plants, the key components of GW’s cannaboid products are carefully extracted and standardized. ”It’s not just street cannabis put into a bottle,” CEO Justin Gover told the Guardian in 2011. “To get regulatory approval, we had to meet very strict standards. We had to know every vial of Sativex is identical.”

The company, which has struck distribution partnerships with some of Big Pharma’s giants, such as Novartis and Bayer, appears to have carved out a niche for itself in the cannabinoid space. “We are not aware of any other company following the same route as GW in the sense of both deriving a cannabinoid medicine from plants’ extracts and going through the full, regulated clinical trials procedure, so as to arrive at approved prescription pharmaceuticals,” a spokesman for GW said via email.

This week the company said it was also progressing with early-stage development of cannabinoid products to treat schizophrenia, diabetes and other forms of epilepsy. But it is the prospect of an alternative to medical marijuana that people are most excited about. Devani says GW is “probably the best positioned for when the regulatory barriers come down, to get through the stringent requirements that the FDA will propose.” Its investors are praying that it will deliver on that promise.