That the Greek government is able to borrow from bond markets again is an accomplishment in itself, given its bailed-out, hollowed-out economy. But the demand for this morning’s five-year issue was breathtaking, with €20 billion ($27.7 billion) in orders chasing only €3 billion in bonds, up from an initial goal of raising €2 billion. As a further sign of the demand, the issue’s final yield—the return investors get on their money—was also lower than predicted, at just under 5%.

Not long ago, similar Greek government bond yields were four or five times higher—meaning that prices were a fraction of what the bonds fetch today. And holders of Greek debt suffered mightily two years ago when the country wrote off more than half of the value of all bonds held by private investors.

So why are investors now back in such a big way? First of all, they never really went away. Greece has been issuing lots of short-term bills for some time. This still doesn’t detract from the symbolic importance of the return of longer-dated paper aimed at international investors. But there is always a certain amount of theater around high-profile issues—the banks that handle them, and sympathetic investors, understand that it’s in the government’s interest to make a splash on its return to the markets—so the blockbuster order book was probably not quite as robust as it seemed.

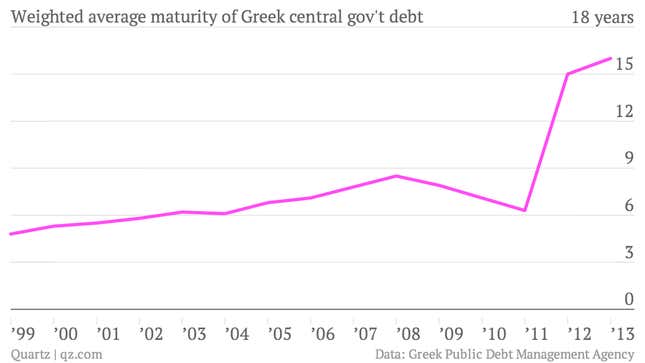

Today’s bonds will add less than 1% to Greece’s formidable public debt. The average maturity of this debt is around 16 years. The longer-dated parts are owed mostly to the IMF and EU, following the country’s two-stage bailout. That means buyers of today’s bonds will be due for repayment before Greece’s public-sector creditors, which gives them some reassurance that they’ll actually get their money back.

More importantly, Greece’s bonds are backed by the tacit pledge of the European Central Bank to keep the euro zone together no matter what. When Irish yields first dropped below all-time records earlier this year, similar factors were at play. If the probability of debt defaults and the disintegration of the euro zone is close to nil, “one could legitimately ask why there is any distinction” between the bonds of Greece, Ireland, Germany or any other euro member, as an economist recently told Quartz.

In this context, Greece’s five-year yield looks awfully tempting against the mere 0.6% that investors get from buying similar German bonds. Retaining some risk premium is warranted, of course—a crippling general strike yesterday and car bomb blast outside of the Greek central bank today are reminders of how volatile conditions remain in the country. Although it may seem crazy given Greece’s fragile state and recent history of financial ruin, the idea of a practically risk-free return of close to 5% is too good for many investors to pass up. That’s an explanation as good as any for today’s Greek bond-buying bonanza.