Wall Street’s traders used to mint money. Not any more. Trading revenues are falling and many big banks are mounting an ignominious retreat from the once-lucrative business of trading stocks, bonds, commodities and funky derivatives. America’s big five—JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Citigroup and Morgan Stanley—reported $21.6 billion in total trading revenue during the first quarter of 2014. That’s down 10% from the prior year, and 41% from the all-time peak of $36.7 billion reached in 2009. (That’s when panicky investors pushed up trading volumes—which generate fees for banks.)

In short, trading has become a smaller and smaller share of the big banking business.

Forget about FICC

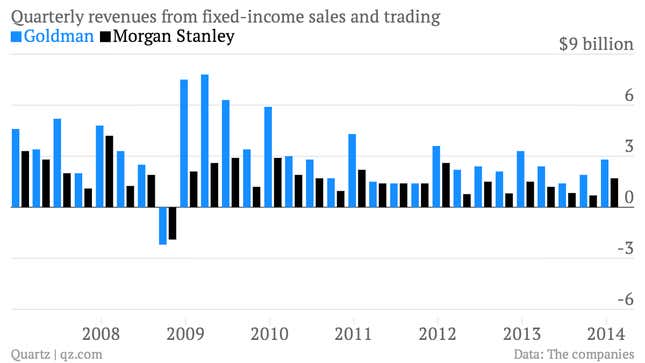

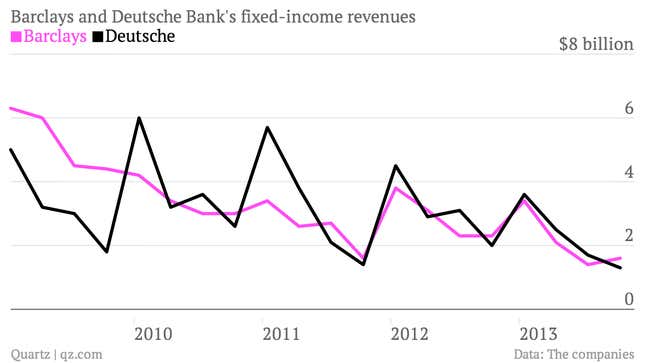

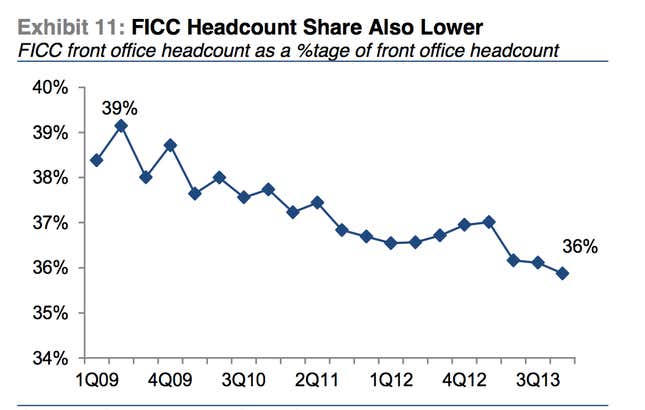

What’s been hit hardest? FICC, the fixed-income, currencies and commodities trading units at major banks. That area formerly was one of the main profit engines for the likes of Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. But that’s changed. New rules—such as the Volcker Rule—have forced banks to cut down on speculative trading. Other regulations—such as the so-called Basel III capital rules—have limited the amount of borrowed money banks can use to amplify the returns, and risks, of the positions they take in the markets. For the record, this isn’t just a US phenomenon. Trading revenues have also slumped at both Barclays and Deutsche Bank, for example. As a result, the herd of FICC traders at US banks is thinning considerably.

Commodities

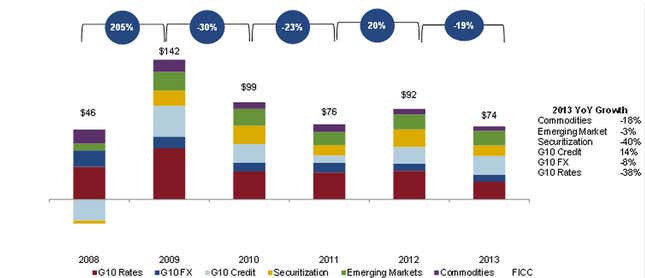

New regulations are also weighing on the commodities trading business. From 2012 to 2013, commodities trading revenues at large banks fell 18%, according to the most recent full-year data from commodities market research firm Coalition. As a share of bank FICC revenues, commodities shrank from roughly 30% in 2008 to about 6% of revenues in 2013.

Why? It’s the same story. Regulations designed to cut down on bank risk-taking are making these businesses less profitable. Regulators are also displeased by some practices in physical commodities trading, which is when financial institutions don’t just trade assets on paper but buy and warehouse loads of raw material such as aluminum. Such operations have come under increased scrutiny in recent years. And the banks seem to see the writing on the wall. JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley have already announced the sale of parts of their physical commodities businesses. Barclays announced last Tuesday that it planned on exiting most commodities trading as well. Goldman Sachs, on the other hand, says its sticking with commodities.

Equity trading

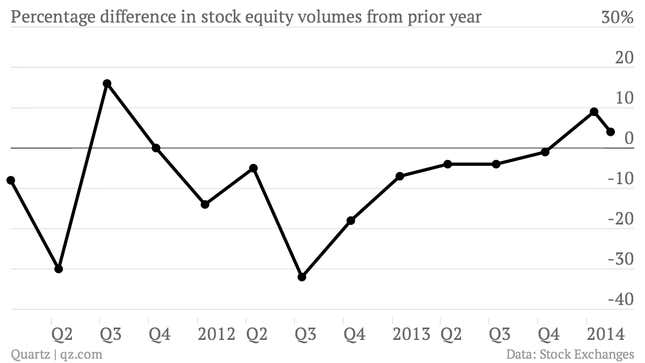

The last several years also have been lean ones for banks’ traditional business of buying and selling chunks of shares to and from large institutional investors such as mutual funds. Equity trading volumes peaked in 2009 and have been suffering since. That means less in fees.

But not only are volumes smaller. “The technological evolution of trading is reducing costs, so banks are making less money on trades,” said Jeff Harte, an analyst covering banks for Sandler O’Neill. In other words, advances in electronic trading—including the much-maligned high-frequency-trading—have made the traditional job of letting equities traders match buy-and-sell orders on behalf of clients much less profitable.

Safer and less sexy

The shrinking trading business at the big banks is a big change. But it shouldn’t be unexpected. In large part, it’s the natural outgrowth of new rules designed to make the financial system safer in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. That might be bad news for traders who used to make serious cash by betting the bank’s money. (Although if they were really good, they can always get a job at a hedge fund.) It also might be bad news for bank shareholders who miss the kinds of dividends they were getting before the crash. (Especially shareholders of Citigroup.) But for the economy as a whole, safety and soundness trumps inflated returns in trading.