Apple CFO Peter Oppenheimer predicted in January that Apple will generate the same amount of revenue this past quarter—the company releases its financials today—as it did a year ago. Analysts agree with him. Apple generated more revenue than ever in the the first fiscal quarter of 2014, which includes the 2013 holiday season. But it’s entirely possible that fiscal 2014 (which runs through September) will be the first time since Steve Jobs returned to Apple and turned the company around that revenue will not grow from one fiscal year to the next.

It is, literally, the end of an era—financially, the biggest bull run of any technology company in history, from $13.931 billion in revenue in 2005 to $170.910 billion in 2013. Apple is still the most valuable public company in the world, a bet by investors that Apple will continue to grow—and it has, until now.

What’s interesting here isn’t that Apple has plateaued—the markets already knocked $45 billion off of Apple’s valuation when the company announced its revenue projections for this past quarter three months ago—but why.

iPhones, steady as she goes

The first place to look would be how many iPhones Apple is selling, since they represented 56% of Apple’s revenue in the first quarter of this fiscal year. But iPhone sales are expected to be flat, as sales through China’s biggest mobile carrier, China Mobile, fail to do much to the overall iPhone story.

The iPhone story is straightforward: people buy iPhones and, subject to the whims of mobile carriers, upgrade them on a regular basis. It’s a fantastic business for Apple to be in, selling devices that cost on average $637 each and are re-purchased by consumers every two years or so, like clockwork.

It’s also important to note that Apple predicts it will miss out on $8 billion in revenue across all of 2014 because the company is now giving away its operating system (OS X) and productivity software (iLife, iWork.)

The iPad as a failed opportunity for growth

Some analysts are predicting that Apple will sell fewer iPads this past quarter than it did a year ago. For a mature product with a predictable pool of buyers—cars, vacuum cleaners, iPhones—this wouldn’t mean much. But considering the iPad is the most recent device Apple invented, defining an entire category and inspiring dozens of copycats, it’s bad news—and not the first time we’ve heard it.

If iPhones are doing what we expect iPhones to do—continuing to be consumed regularly by a market that seems at this point to be more or less saturated—then the story of Apple’s revenue plateau is the story of missed opportunities in the one device that many expected to be Apple’s next big growth opportunity—the iPad.

The iPad isn’t insignificant. It’s about 20% of Apple’s revenue. But it could be more. The iPad was supposed to replace the PC, after all. Indeed, that could be its problem.

If iPads are PC replacements, demand for them is equally soft

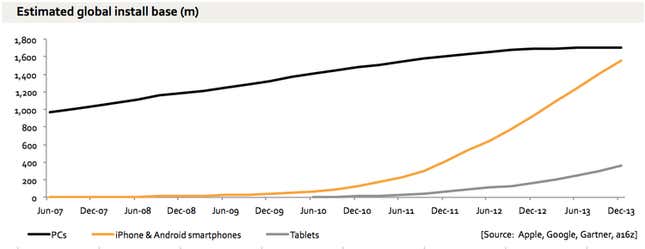

A notion that until recently seemed to be churlishly anti-Apple—that in contrast to phones and PCs people don’t really need tablets—is now virtually mainstream. Smartphones are replacing everything, including tablets.

How is this possible, when tablets came second?

One possibility is that the novelty of tablets, or at least Apple’s models, has worn off. Tablets were supposed to be magic, and the wealthy bought them expecting something as transformative as the iPhone. But the main use case for many tablets is probably as personal internet-connected TVs, not bicycles for the mind. If what we’re really doing with tablets is simply asking them to play HD video without it stuttering, you certainly don’t need to pay a premium for Apple’s iPad to get a satisfying user experience.

Tablets that are mainly used for browsing the web and watching videos don’t need to be re-purchased nearly as often as phones that are getting lost, stolen, broken, or simply radically more useful as time goes by and the number of apps and use cases for them multiplies. That puts tablets on a replacement cycle more like PCs—every five years or so—than phones, which is another reason you’re not seeing sales on the same order as phones.

It’s not that people aren’t buying tablets. But the adoption rate is nothing like what we’ve seen in smartphones.

And overwhelmingly, the tablets that people are buying are the cheaper models—witness the success of UK grocery giant Tesco’s branded tablet, 500,000 of which have been sold in the past seven months. If a cheap tablet is the only computing device to which you have access, it can be transformative, which is another reason global demand for tablets—but not Apple’s iPads—continues to expand.

On any timescale relevant to investors, there will never be another iPhone

The story of Apple’s growth is the story of the phenomenal success of the iPhone. There is no other category of electronics with as much potential demand as there is for smartphones. Many analysts are saying the rumored iWatch or some combination of wearable computers could be Apple’s next iPhone-scale blockbuster, but that’s ridiculous, notes MacWorld’s Jason Snell:

IDC reported that in 2013, one billion smartphones were shipped, up 38% from the previous year. That’s a fast-growing market worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Meanwhile, on Thursday IDC predicted that the wearables market will reach 112 million units in 2018.

In other words, in four years the wearables market might grow to be one-tenth the size of today’s smartphone market—in units shipped. Presumably the average selling price of wearable items will be a fraction of that of smartphones, meaning the dollar value of the wearables market is even more minuscule compared to the smartphone market.

What about iTunes and AppleTV? Unlike Amazon, which sells hardware in order to sell software and content, for Apple it’s the reverse. In fiscal 2013 Apple made $16 billion from iTunes, but growth in this stream of revenue is slowing. Apple TV, meanwhile, is a supporting technology—it remains, as Jobs once put it, “a hobby.” As Rene Ritchie put it at iMore:

The truth is Apple makes two kinds of products. They make the flagship products that support their business, like the iPhone, iPad, Mac, and iPod. And they make the supporting products that increase the value of their flagship products, like the Apple TV.

The Apple TV is a great product and could, if rumors of a hardware update and Game Store prove true, become a really great one. But it won’t be a hundred million unit selling, multi-billion dollar profit making one any time soon.

This is what a mature market for (very) personal computers looks like

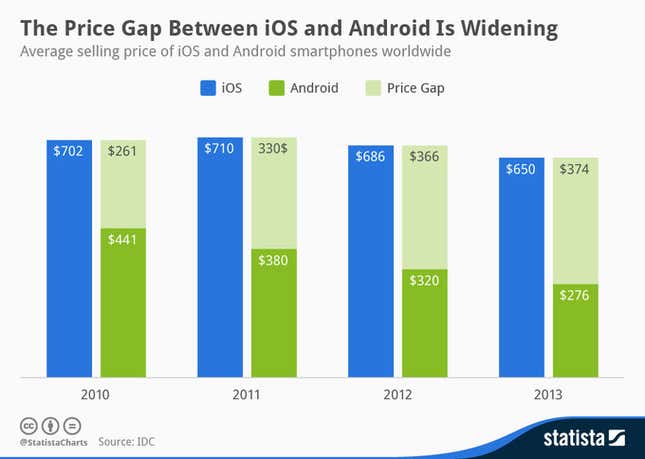

Apple makes premium electronics, mostly computers we carry in our pockets that are connected to the cloud through a system of cellular base towers that might as well be magic. That market is now, apparently, saturated. Millions of people are coming online every day, and they might aspire to own an iPhone, but it’s lower-priced Android handsets that they can afford and end up purchasing. Comparisons of Apple’s market share to that of Android smartphones elide the fact that the overwhelming majority of Android smartphones are much cheaper than the iPhone—at this point, costing less than half as much.

That price gap isn’t just Apple’s margin—Samsung’s latest flagship smartphone costs almost as much as the average iPhone, factoring out any operator device subsidy to the consumer. Most Android phones and tablets are essentially different devices than Apple’s, suited to different sorts of tasks or to doing the same tasks in a way that annoys some people (i.e. Apple fans) and not others.

What we’ll be looking at, in the numbers Apple will release Wednesday, is the holding pattern of a hulking technological Colossus. Apple’s immediate prospects for growth are dim not only because of the law of large numbers, but also because the world presently has just about as much Apple as it can take.

Apple can still build on top of its current base

The second half of fiscal 2014 is very likely to be when Apple gives investors and fans reasons to be excited again. Rumored launches include a larger iPad and iPhone, as well as the iWatch. But none of these are going to be category-busting devices on the scale of Apple’s current businesses. Assuming Apple keeps its iPhone customers loyal by more or less keeping pace with developments in Android—not a foregone conclusion—these new devices mean there’s still potential for incremental growth in Apple’s revenue. But that’s it.

From the perspective of the markets, it seems Apple has become a company like those it not so long ago sought to disrupt—Microsoft, Intel, IBM. Buying back shares, paying dividends: this is what you do for shareholders when you can’t promise them the kind of growth that was once seemingly inevitable.