For months, Bank of England governor Mark Carney (pictured above) has been beating back suggestions that he is about to raise interest rates.

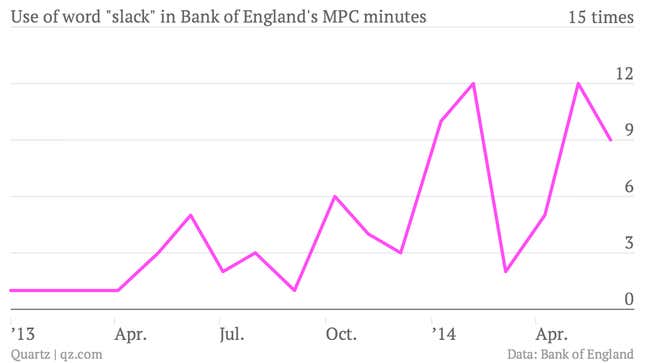

Earlier this year he hastily tweaked the bank’s “forward guidance” policy, after the UK unemployment rate unexpectedly dropped below the level the bank had said would trigger a rate hike. The bank now tracks “slack” in the economy as its main gauge for where to set its benchmark rate, which has been rooted at an all-time low (0.5%) for the past five years.

Carney and company reckon that there is still slack, or spare capacity, worth between 1% and 1.5% of Britain’s GDP. Until this is absorbed by a combination of stronger growth, more jobs, and higher wages, rates won’t rise. The bank released the minutes from its latest rate-setting committee meeting today (pdf), and officials’ preoccupation with slack remains intact:

In the minutes, bank officials suggest that their estimates of slack haven’t changed. Still, in a speech last week Carney dropped the strongest hint yet that rates could rise sooner rather than later.

The latest minutes reinforce this thinking—in a bit of meta-commentary, Bank of England officials found it “somewhat surprising” that financial markets were pricing in a low probability of a rate hike this year. There is a “risk” that the UK will grow faster than expected—it has consistently surpassed expectations in recent quarters—and, as a result, “slack would be absorbed more quickly than had previously been expected.” London’s frothy property market is a particular worry, with some in the homebuilding industry even calling for London-specific rate hikes (paywall) to deflate the bubble.

Whatever the case, future rate hikes will be done ”gradually and cautiously,” the bank says. But in a speech today (pdf), rate-setting committee member Martin Weale noted that this policy of gradualism implied ”that the first rise needs to come sooner than would otherwise be the case.”

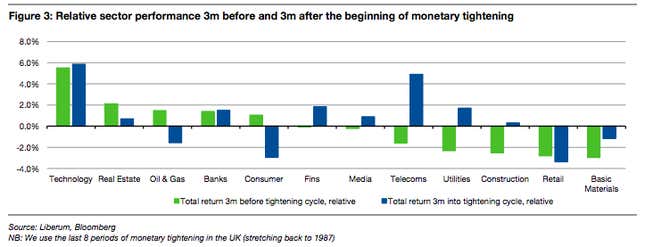

And so it seems that the Bank of England is poised to become the first major central bank since the 2008 financial crisis to raise interest rates, perhaps sometime later this year. This has analysts scrambling to assess the impact—the UK team at Liberum, a brokerage, ran the numbers going back to the late 1980s, and concludes that technology, real estate, and banking stocks tend to outperform before and after tightening cycles, while retailers and miners often suffer: