Netherlands prime minister Mark Rutte, whose citizens make up the bulk of the victims of the MH-17 disaster, didn’t mince words this week when telling Russian president Vladimir Putin about his responsibility to improve the situation there: “I told him that the window of opportunity to show the world that he intends to help is closing rapidly. He must take responsibility vis-à-vis the rebels and show the Netherlands and the world that he is doing what is expected of him.”

Soon after, the pro-Russian rebels who initially blocked access to the crash site began the process of sending the victims’ bodies back to the Netherlands and turning the plane’s black boxes over to Malaysia.

But if, as many Western governments allege, MH17 was shot down by an anti-aircraft missile supplied by Russia, Putin may have hurt one of his country’s closest economic friends, a nation that spent 2013 celebrating the Dutch-Russian bilateral relationship. Now, Dutch prosecutors have announced an investigation into the destruction of the airliner that will seek to charge those responsible with war crimes even as Dutch politicians face pressure to punish Russia financially.

The deaths of so many EU citizens in the air disaster is expected to galvanize the bloc’s response to the crisis in Ukraine. While the US has pushed for tougher sanctions against Putin’s regime, Europe’s economy is much more intertwined with Russia’s, making it harder to avoid damaging its own economies should policymakers level serious sanctions. Russia, for example, is the Netherlands’ second-largest supplier of gas.

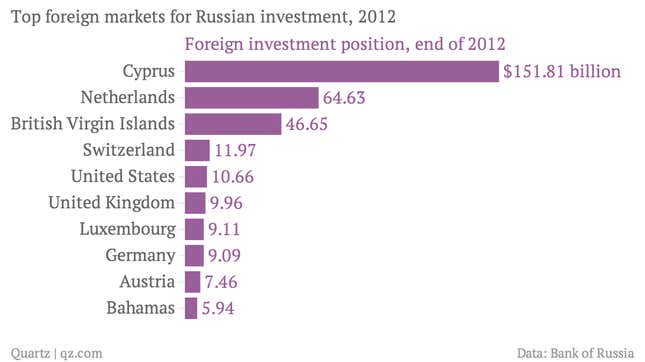

But those close connections are the same reason that such sanctions would be effective against Russia—Europe is home to hundreds of billions of dollars of Russian foreign assets, with key holdings in the Netherlands including those of state oil companies like Rosneft and Gazprom, as well as companies like Gunvor that are allegedly controlled by Kremlin figures.

It’s no accident that Netherlands is one Russia’s largest offshore-financial centers—it has actively welcomed capital flows from multinational companies seeking to avoid taxes and scrutiny, and it just so happens many of those companies are Russian, often with ties to the Kremlin. That capital is useful for a small country like the Netherlands, but if investigators are able to prove allegations of Russian involvement in the air disaster, it will put the Netherlands’ financial sector in an uncomfortable bind: Can it be a banker to Russia’s biggest companies while Putin’s regime supports groups that murder Dutch citizens?