The co-dependence of Russia and Europe has complicated efforts to punish Russia economically. The latest wrinkle is the fact that Russians love to park their money in tax havens under the European Union’s jurisdiction; and the countries involved love Russian cash just as much.

We ran into this in 2013, when Cyprus faced a financial crisis and European officials were reluctant to bail out Russians who were keeping their money on the Mediterranean island to avoid taxes and scrutiny at home. After a brief break, Russian money has been flooding back to the island.

But Cyprus is not the only place where that cash winds up. Here’s are the top 10 countries for Russian foreign investment in the first three quarters of 2013. (The Netherlands is also included—it lost $4.6 billion but is still one of the largest holders of Russian foreign investment.)

See that big spike in the British Virgin Islands? A lot of it is related to a deal by Rosneft, the Russian state-controlled oil firm, which purchased a stake in another oil firm registered in the islands, which are often used as a tax haven. Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin is on both the US and EU sanctions blacklists, but his company is not—in part because it’s not clear whether Ireland, the Netherlands, Cyprus or Switzerland, all countries with Rosneft subsidiaries, are willing to crack down on the company and others like it by freezing assets.

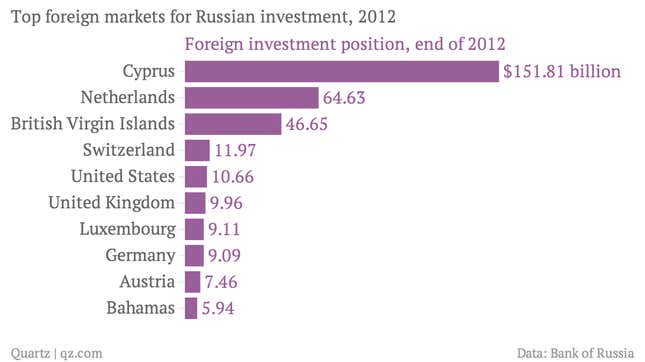

One reason that Russians keep so much money abroad is that states such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg aggressively advertise for it, promising low taxes, more reliable rule of law than Putin’s Russia, and in many cases, easier access to offshore tax havens. Those pleas have worked: For a broader of view of where Russian money is, we can look back to the end of 2012, the last date where the Bank of Russia released data on Russia’s total investment positions. Here are the top ten positions, equal to almost a fifth of Russian GDP:

It’s likely that these positions have changed in the past eighteen months, but you can see how much cash winds up in places where it is easy to hide. Not all of it is necessarily hidden from Putin; indeed, some if it may belong to him.

At the same time as Putin and the oligarchs who support him rely on the offshore system to shield their wealth, the practice is a handicap for the Russian economy at large. Capital flight is a big problem and getting bigger: In just the first quarter of this year, $50 billion in net capital has left the country. Last year saw a departure of $59 billion. Putin has complained about this trend, urging oligarchs to move their assets back. (That’s one reason that US professional basketball playoff contenders the Brooklyn Nets are technically based in Russia.)

All these assets are technically within reach of Western authorities; but it remains to be seen whether they’re willing to upset the cozy structures of offshore finance, even to hinder Russian aggression.