Remember Excite? How about AltaVista? Maybe Lycos?

They were all competitors to Yahoo, back when finding interesting things online meant going to a web portal (or typing in a web address you had committed to memory). Portals were appropriately named: they really were the gateway to the world wide web. But the gateway was narrow. With search technology in its primitive stage, peddling links is what the web companies mainly did. Then Google came along with its tabula rasa of a homepage and changed the way people used the web. We moved from clicking on pre-ordained links to being able to find whatever we wanted.

Today, on the mobile web, we are back where we started. It’s possible to search for things, but the place is a mess. Uncovering hidden features of apps—or wading through app stores just to find apps—remains a challenge.

The internet giants of the present era are rushing to fix this, in essence competing to become the Google of mobile. In the meantime, there’s an assortment of enterprising companies betting on a very familiar business model: to be the portal through which people access the (mobile) web. And they all start with messaging—just like the portals of a decade ago kept their users coming back by giving them free, web-based email accounts and desktop-based messaging apps.

Today’s major messaging platforms have one other very important thing in common: they all came out of thriving, web-based portals.

Not just talk

The latest entrant is My.com. It comes from Russian web portal Mail.ru, and has its sights on the US market. So far, the service includes a messaging app, an email app, and a gaming platform. Email is an odd one here, one that no other messaging platform has ventured into. Dmitry Grishin, the chairman and CEO of Mail.ru, says email use actually is growing on mobile: Thanks to instant notifications, people send more email than ever before.

But that’s not really the point. The goal is to keep users on platform; it doesn’t matter whether that’s through email or messaging. “We can make strong communications tools and grow the audience, and we can use games to make money,” Grishin says. “I think it’s very good for users also because we can make our [email] client free, because we can use it as a platform for making money on games.”

An ever broader remit

Grishin’s strategy is similar to other regional giants that started as messaging apps but grew into full-service mobile platforms. John Park, a business development manager at Line, the hit messaging app in Japan, describes his company as much more than a messaging app. “Although messaging is our core feature, we like to think we’re part of a broader social network,” he says.

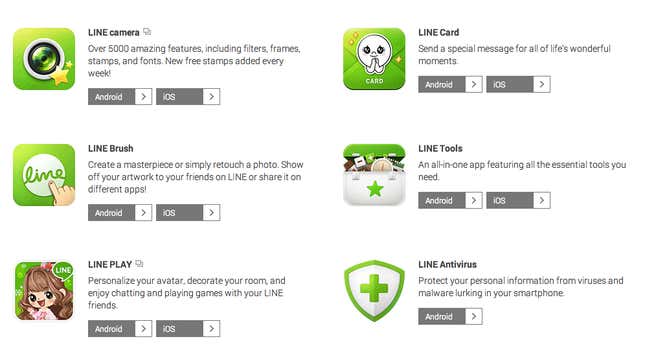

Line’s messaging app allows users to take videos, features a “timeline” not unlike Facebook’s, and encourages users to follow brands. Just last week, Line introduced the ability to buy and sell stocks through its app. It also trades in games. Line’s extended family of apps includes a camera, group messaging, touch-based drawing, greeting cards, an anti-virus program (only for Android), and more. The whole bunch have together been downloaded over 1 billion times, says Park.

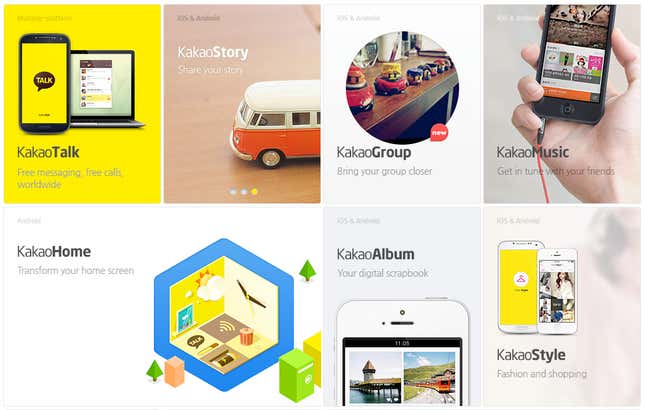

Kakao, the messaging app popular in South Korea, is similar. In addition to a sophisticated messaging app, it offers a baffling array of supporting apps, including a scrapbook, a fashion app, a travel app, and a gaming platform. KakaoStory is like a souped-up Facebook. Among its many fun features, it allows users to insert cartoon characters into photos, as Kakao user Andrew Jackson did with The Creation of Adam. (His handiwork is pictured at the top of this piece.)

Kakao describes itself as “a social mobile platform.” It is “almost like a gateway on mobile, for discovering new content, for accessing different applications, for meeting new friends, and new people,” says Kakao spokeswoman Sonia Im. In 2013, 84% of Kakao’s revenue came from “commissions,” primarily earnings from games. Line, and newcomers like Tango and My.com, work on the same basis.

But perhaps the best example of a messaging app that has far exceeded its remit is China’s WeChat, arranges celebrity wake-up calls, has its own app-enabled vending machines, offers promotions on cancer insurance, and facilitates shopping, mobile payments, and pretty much everything else you can think of.

One major exception to the mission-creep trend is WhatsApp, which remains steadfastly a messaging app and nothing more. It can afford to be singular in its focus thanks to its gigantic user base and, more importantly, its acquisition by Facebook, which is itself in the process of turning into a web portal of sorts. WhatsApp’s model may be the last of its kind, as messaging alone looks set to become commoditized by services like Layer, which allows developers to simply plug a sophisticated messenger into their apps and websites.

A long pedigree

Web portals have long since ceased to command the attention they once did in the West, though relics like aol.com (whose AOL Instant Messenger has been around since 1997) and yahoo.com (remember Yahoo Messenger and Yahoo chatrooms?) still persist. The web stopped being a mish-mash of disconnected properties as big companies bought up popular websites. Facebook became a substitute for portals, and owns both WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. Google disaggregated portals into its panoply of services, and has Gchat and Google Hangouts. Microsoft still runs msn.com but folded MSN Messenger into Skype, which Microsoft also owns.

Web portals remain popular in Asia and elsewhere. WeChat is owned by Tencent, which runs QQ, one of the top-10 most frequented sites on the internet. In China, it is second only to the search engine Baidu.

Line came from Naver, Korea’s largest web portal. KakaoTalk is in the process of merging with Daum, Korea’s second most popular web portal. Mail.ru, the portal that launched My.com, also owns Russia’s second-largest social network, Odnoklassniki, as well as a controlling stake in the largest, VKontakte. (It also owns ICQ, which has a strong claim as the first-ever viral messaging app and is growing again.)

The business model may have changed from relying on ads to relying on games, but messaging platforms, hot as they are now, are a very old idea from some of the very same portals that shaped internet usage in the first place.