Nearly 4.3 million people have registered to vote in Scotland’s referendum on independence, the largest electorate ever recorded in the country. With polls showing the Sept. 18 vote as too close to call, the campaigns are appealing to every niche in that electorate in hopes of tipping the balance.

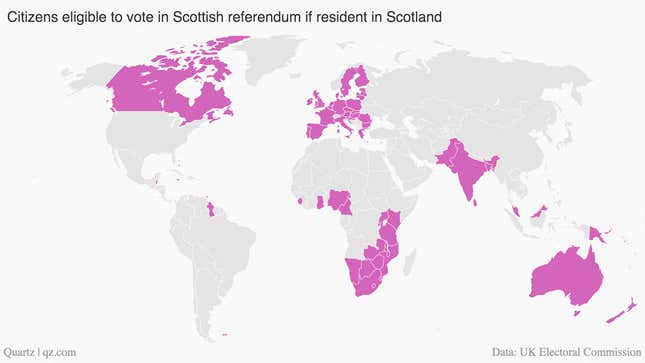

One constituency that could prove decisive, given the tight margins, is non-Scots. Some 500,000 English, Welsh, and Northern Irish will vote in the referendum, and polls show they favor maintaining the union by a large margin. But since the referendum will follow the same rules as local elections, the voters also will include more than 100,000 people from elsewhere in the EU and Commonwealth who are resident in Scotland.

Altogether, non-Scots make up about 14% of the potential referendum electorate.

The latest polls show non-Brits also favor the “No” (to independence) camp, but by a smaller margin than Brits born outside of Scotland. Scottish National Party leader Alex Salmond held a rally last week in Edinburgh specifically for foreign voters (pictured above), urging them to vote “Yes”—or “Ja,” “Sí,” “Tak,” and many other variations. It is part of a concerted campaign to win over foreign-born voters to their side.

From Krakow to Caledonia

There are more than 80,000 Poles living in Scotland, the biggest foreign group by far. Although likely voters will be a smaller subset of this, it is still a constituency that cannot be ignored. A survey of Poles in Scotland last month (pdf) found that 85% planned to vote, and a majority favored the “No” side.

Until fairly recently, Ewa Golebikowska was among them. She moved to Scotland from Poland eight years ago, where she has worked for others, ran her own business, and spent time unemployed. “I don’t see how any of those situations could have been improved by Scotland not being independent,” she tells Quartz. She is now a “Yes” voter.

“There is a history of us struggling for independence,” she says. This could be a “subconscious reason” for her to vote for an independent Scotland, she adds. “Poland has done much better since it became independent.”

Other foreign-born groups bring their backgrounds into the campaign for an independent Scotland. This is how the “Italians for Yes” group dismisses the “No” campaign’s recent promise to devolve more power to Scotland if they remain in the union:

Given what’s going on at home for members of the “Yes Scotland Hong Kong” group, they may also be sympathetic to Scotland’s independence from the larger United Kingdom.

Migrants for immigration

Unsurprisingly, a big issue for many “Yes”-leaning, foreign-born voters is immigration policy. This is particularly relevant for EU nationals, who are guaranteed freedom of movement within the bloc by its founding treaty.

British prime minister David Cameron isn’t so keen on such open borders for EU citizens coming to Britain, and has promised a referendum on EU membership if his party wins the next election. The burgeoning support for the far-right UK Independence Party, which is much more popular in England than the rest of the UK, also makes some migrants nervous.

Although it remains unclear how easily an independent Scotland could rejoin the EU, the “Yes” camp claims that other EU members would be unlikely to reject a small, peaceful, democratic country keen to belong. And as the UK’s relationship with the EU becomes increasingly fraught, some pro-European referendum voters figure that it’s safer to vote Scotland out of the UK before the UK votes itself out of the EU.

Sylvie Burnett moved to Scotland from her native France 30 years ago, “and I’ve never felt a foreigner at all,” she says:

In Scotland there is an aging population and they need the immigrants. They are made very welcome. They’re not looked at the same way as they are in England.

Burnett has helped run the “EU Citizens for an Independent Scotland” group, which she started with some German friends. It has gotten nearly 15,000 “likes” on Facebook.

Alexia Grosjean, a Belgian, has lived in Scotland since the late 1980s, but still frets about immigration policy. “One of the major positive factors of the ‘Yes’ campaign is that it is very keen on the EU,” she says. “It’s a very important and worrying aspect for me that Westminster seems to be pushing ever closer to leaving the EU.”

An appeal to history

Throughout the referendum campaign, the polls have shown the “No” camp ahead, although “Yes” voters tend to be more vocal and prominent in public (and willing to talk with journalists). Whether the pro-union’s “silent majority” will deliver a victory later this week is not assured, and in some small part will depend on how of non-Scots feel about the prospects for their adopted homeland.

Grosjean teaches at the University of St. Andrews, where she focuses on 17th-century Scottish history, predating when the country signed the Act of Union with England in 1707. “For me, it never seemed an odd concept that Scotland could be independent,” she says. “It had been for about 1,100 years before it joined the union.”