Though separated by a span of two or three decades, the similarities between Japan’s growth model and China’s are striking. As we recently discussed in longform, present-day China shares with the Japan of the late 1980s a reliance on investment-driven growth, financial repression, cheap money, an enormous housing bubble, to name just a few similarities.

The question is, will the consequences be the same too? Will China be able to avoid the decade-plus of low growth that resulted from the excess of Japan’s model? It’s certainly possible, argue David Cui and Naoki Kamiyama, equity strategists at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, in a note today. It comes down, they say, comes down to whether or when China recapitalizes its banks.

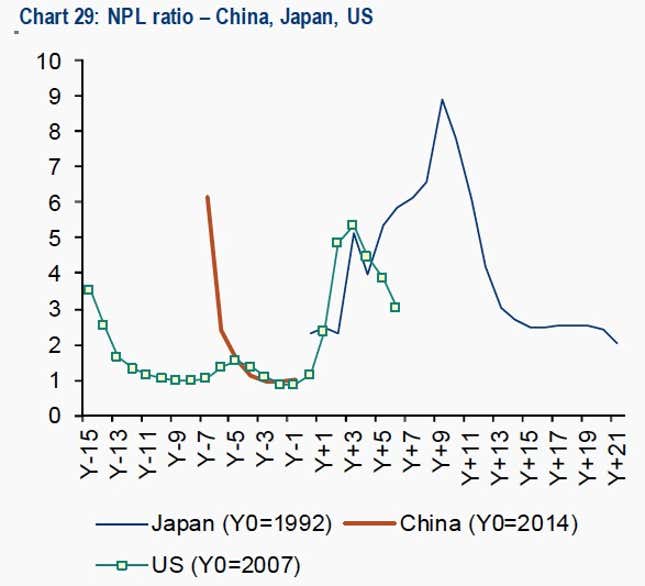

After Japan’s housing market began crashing in late 1989, Japanese businesses struggled to make money while paying down enormous debts on assets that were no longer worth very much. The result was a surge in bad loans, or in banking parlance, “non-performing loans” (NPLs). Unaware of—or unwilling to recognize—the volume of bad loans, the Japanese government for a decade failed to inject banks with the money that would let them write down the never-to-be-repaid loans without going broke.

While it dithered, the Japanese government fed “zombies,” keeping unprofitable companies afloat with new loans while making it impossible for new companies to compete. Its hesitation was costly; between 1992 and 2000, Japan implemented seven stimulus packages and one revitalization plan, totaling ¥110.8 trillion ($1.1 trillion in 2000 dollars). Japan’s GDP averaged 0.8% growth during that time.

Things only turned around, say Cui and Kamiyama, in 2002, when the Japanese government accepted that bad loans could affect the whole economy—not just the banking sector—and recapitalized banks.

China may be on the cusp of an even sharper asset-prices slump than it’s already seen, they argue, noting that there “are strong signs that both the property inflation and debt increases are buckling under pressure.” Though Chinese banks wrote down more bad debt in H1 2014 than in all of 2013, the official NPL percentage is still tiny.

But while it’s hard to know how many bad loans are in China’s financial system, Cui and Kamiyama think the volume will be much higher than Japan or post-2007 America had to face. The last time China had a big banking bailout—in the late 1990s, as state-owned banks prepared for public listings—two-fifths of loans were bad—and that was without a property bubble.

Even if China’s bad-debt ratio is only the 8% that Japan’s banks experienced, the sooner the government bails out the banks, the better, argue Cui and Kamiyama. The problem is that recognizing bad debt will hobble growth for a time—an unappealing choice for a new administration that’s been busy consolidating power. If that is what’s delayed Xi Jinping from fixing China’s debt woes, say the strategists, a bailout will probably have to wait until after the “political dust settles”—perhaps a year or two. And the longer China’s leaders delay, the bigger the bad-debt pile gets.