To understand the Chinese economy’s fraught relationship with property investment, let’s turn for a moment to the wisdom of Homer Simpson:

Sure, Homer was holding forth on booze, not mortgage loans. But just like alcohol, China’s property construction sector—which it relies on to drive up to a fifth of its GDP—is at once “the cause of, and solution to” if not all, then many, of its economic problems. That’s because even though this over-reliance makes the country’s economy unusually vulnerable to home-sale slumps—and financial risks—the government has in the past rescued its swooning economy by—you guessed it—encouraging more real estate investment.

These days, however, that investment more the cause of problems than the solution.

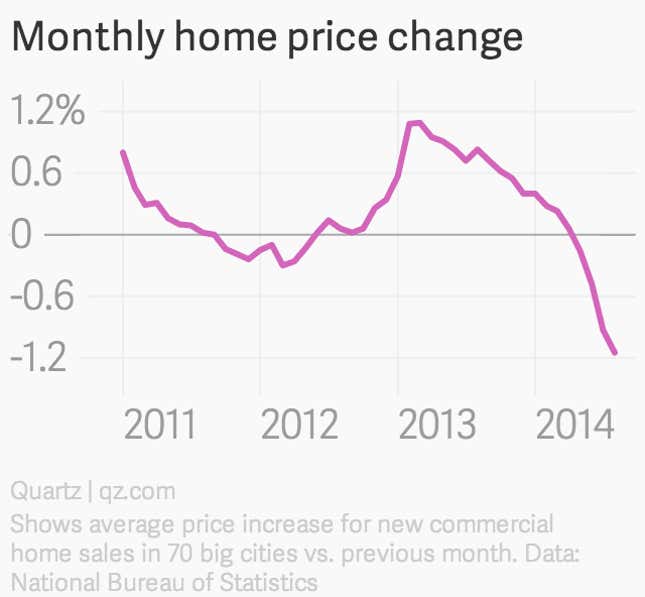

In August, home prices in the 70 big Chinese cities tracked by the government dived 1.2% versus the previous month—a sharper drop than we saw in July, when prices fell 0.9%. Both investment and housing starts fell last month as well. If this continues in September and October—the traditional peak sales months—the Chinese economy will be in real trouble.

Can property investment also offer a solution to these woes, though?

It has in the past: The Chinese government dodged two previous housing crashes—one from mid-2008 to mid-2009, the next from late 2010 to mid-2012—by relaxing mortgage restrictions and loosening credit.

And it’s going for a hat trick. Now 39 out of 46 major Chinese cities have loosened restrictions on whom can buy houses, and how many, says Ting Lu, an economist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, in a note today, adding that the government’s earlier edict to banks to discount mortgage loans seems finally to be kicking in.

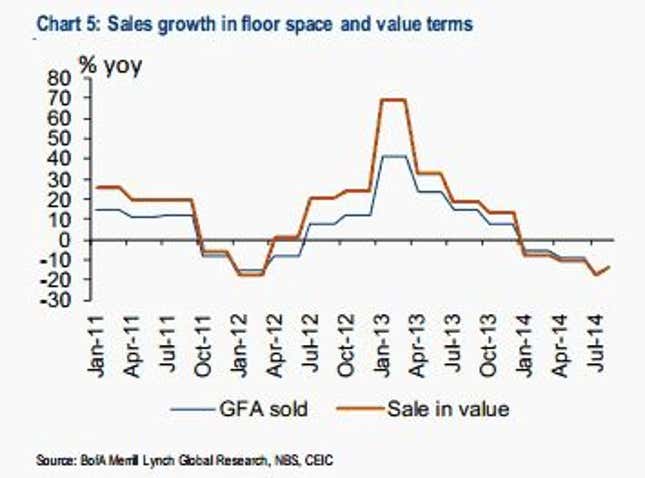

Those new policies, says Lu, are partly to thank for what he sees as the market’s bottoming out in August. New home sales in terms of value and area sold both plummeted nearly 14% in August, compared with August of 2013. Ugly, sure—but not as wretched as the almost 18% plunge that both metrics took in July of this year.

But not everyone agrees that the government’s solution is having an impact. Despite credit easing for home buyers, prices “are now falling at the quickest pace ever,” says Wei Yao of Société Générale; and even plunging prices have “not been able to stop the slide in housing sales.”

Why is Homer’s trusty maxim failing? The boost to property lending won’t be anywhere near enough to put a dent in China’s huge oversupply of houses, says Yao.

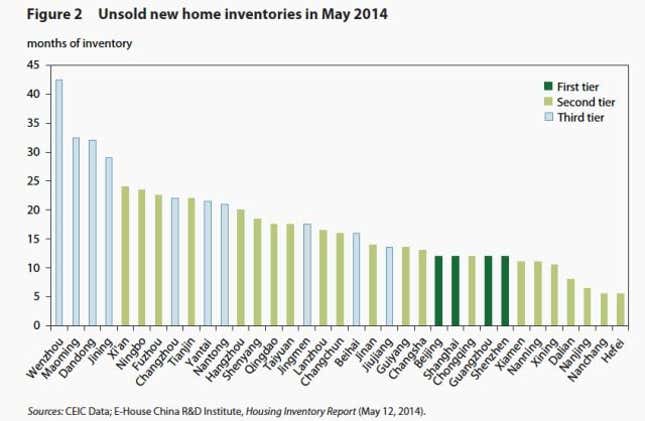

That glut is much bigger than in the past two downturns, says, David Cui, a strategist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch. It would now take 4.1 months to sell all of China’s unsold vacant apartments, assuming sales continued at the average pace of the last 12 months. That’s up from 2.5 months in March of 2012 and 3.1 months at the end of 2013.

Dividing inventory by the six-month average—closer to the current pace—makes things even scarier (via the Peterson Institute for International Economics).

So what if stimulating property investment can’t solve this housing market slump? It could shave as much as three-quarters of a percentage point off China’s 2014 GDP, says SocGen’s Yao—e.g. knocking 7.5% GDP growth down to 6.75%. If she’s right, China could be setting itself up for one very nasty hangover.