There are lots of headlines out of Dublin today about the end of the “double Irish,” a notorious tax break used by multinational companies to avoid paying government levies around the world. Don’t be fooled: The Emerald Isle isn’t giving up on its race to the bottom of the tax world. It’s just making its strategy to attract global profits more transparent.

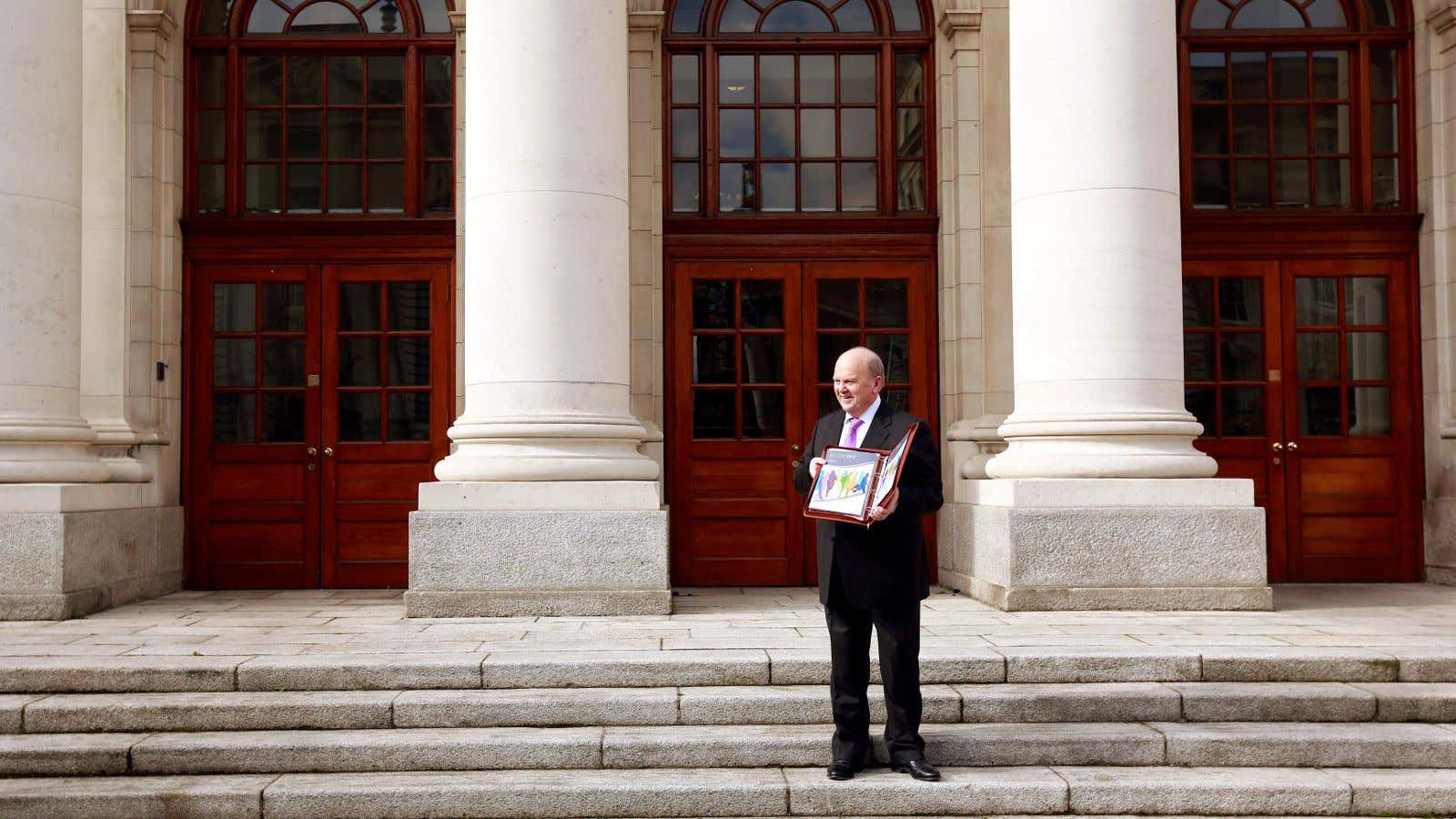

Finance Minister Michael Noonan announced a plan today that will force shell companies to start paying Irish tax—in 2020, after a six-year adjustment period. Apple, which saved billions by running its business through a stateless company in Ireland, is one of the most prominent users of the “double Irish” tactic, along with Google, General Electric, and Wal-Mart.

The absurdity of hosting stateless companies made Ireland an easy target, inviting scrutiny from cash-strapped governments in the US and Europe, and from the OECD, the policy-coordinating club of wealthy nations. The European Commission has issued a preliminary finding that a special deal Ireland negotiated with Apple to cap the company’s tax rate violates the common market’s rules about illegal domestic subsidies; if the final ruling agrees, billions in fines could follow.

So a step towards a less obvious way to attract global financial flows makes sense, especially if it can protect the bedrock of Ireland’s advantage in being a financial way-station for global firms: an extremely low corporate tax rate and permissive tax treaties with tax havens like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands.

Indeed, even as Irish officials announced the closing of one loophole (a development that the most influential tax lobbyist in Ireland predicted last year, without much worry) they announced the opening of another: the country plans to develop a special tax regime for intellectual property (IP), called a “knowledge box.” Essentially, it will give a special, lower corporate tax rate to companies on profits derived from IP.

Of course, moving IP overseas and using licensing structures is at the heart of the existing tax avoidance and profit-shifting schemes under criticism in Ireland. This provision largely would formalize what companies have been doing in private negotiations with Ireland’s revenue office: Setting a lower tax rate in exchange for moving profits earned in higher-tax markets to Ireland. At least this method, used in the UK and the Netherlands, offers transparency in lieu of back-room dealings. It probably will offer something higher than Apple’s infamous 2% rate but lower than the UK’s 10% levy on IP profits.

So while it seems that Ireland is coming clean on its tax loopholes, don’t be surprised if today’s announcement isn’t the final word on complaints about Ireland’s tax regime or the creativity of multinational tax lawyers and accountants.

Of course, it is worth noting that when it comes to multinational corporations, tax policies go two ways: The US, for example, could take action at home to prevent companies from exploiting the tax avoidance capabilities of their foreign subsidiaries, but such reforms are dead in the water in Congress thanks to the united opposition of the Republican party and the business lobby.