In his state-of-the-nation address to lawmakers last week, Russian president Vladimir Putin had some distinctly unfriendly words for who he called “our American friends.” The US is always meddling in Russia’s regional affairs, Putin said, “either openly or behind the scenes.”

Less predictably, the president also picked on a much smaller opponent: Cyprus. Russian businesses abroad can be “fleeced like a sheep,” Putin said, and cited last year’s emergency levy on Cypriot bank deposits as proof. As a condition of the country’s €10 billion ($12.3 billion) bail-out, a chunk of unsecured deposits at the Mediterranean island’s biggest banks were seized to help pay for the rescue.

Since Russian companies and individuals hold around a quarter of bank deposits in Cyprus, they suffered large losses in the March 2013 bail-out, alongside local savers. In his speech, Putin recalled this pain in order to gain support for his long-running plan to “de-offshorize” the Russian economy:

I am confident that we should finally close, turn the “offshore page” in the history of our economy and our country… I expect that after the well-known events in Cyprus and with the on-going sanctions campaign, our business has finally realized that its interests abroad are not reckoned with and that it can even be fleeced like a sheep. And that the best possible guarantee is national jurisdiction, even with all of its problems.

To encourage investors to bring their money back to Russia, Putin announced a one-time, no-questions-asked amnesty for returning funds.

Repatriating resources squirreled offshore has gained greater urgency since Russia’s economy has stagnated and its currency collapsed, putting a strain on the government’s budget. That’s why Putin called out Cyprus, a country with a population of less than 900,000 people but tens of billions of dollars in funds that belong to Russians.

Shelter in a storm

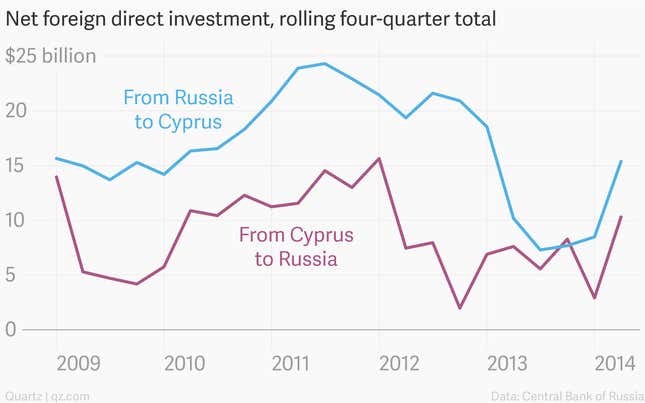

For years, Russians have been attracted by Cyprus’s amenable laws, EU status, and the army of advisers that has sprung up on the island to help foreigners set up shell companies to shield their assets from the higher taxes and unpredictable regulation they face at home. In recent years tiny Cyprus has consistently ranked as one of Russia’s largest partners for both inward and outward investment—largely a function of Russian funds making a roundtrip via the low-tax island jurisdiction.

Tellingly, two years before it called in the EU and IMF for a bail-out, Cyprus turned to Moscow for a low-interest loan when its finances first started looking shaky. The Kremlin’s influence over the island has been a persistent irritation to many other EU members ever since.

But Putin is no longer in the mood to share the wealth. He wants his countrymen to park their cash permanently at home. Will the amnesty work?

Despite the rough treatment during the Cypriot bail-out, the flow of funds between Russia and Cyprus is bouncing back:

On the sidelines of a conference in Limassol, local lawyers, accountants, and bankers told Quartz that business from Russian clients was holding steady, an observation that squares with other recent accounts. (Some have dubbed the city Limassolgrad, given its role as a hub for Russian businesses.)

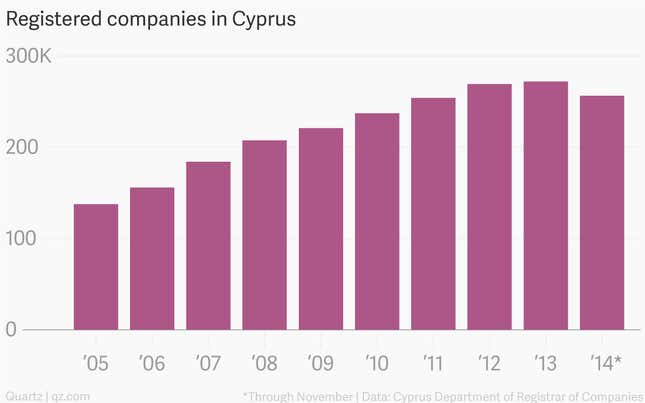

Indeed, it doesn’t look like companies on the island are being wound up in meaningful numbers:

Paradoxically, many of the city’s professional advisers think that the Kremlin’s measures to bring funds back home could have the opposite effect.

The amnesty is attractive in theory, but it assumes that Russians are keen to park their money in Russia’s sanctions-hobbled banks or invest in the local market’s incredibly volatile assets. And the carrot of the amnesty is made less attractive by the stick of tougher tax rules introduced to capture more revenue from residents’ foreign holdings. One way around these rules is for Russians to move their residency in addition to their money, and Cypriot advisers say they would be happy to help them do so. Investing €2.5 million in the country can buy a foreigner full citizenship.

Home and away

Cypriot finance minister Harris Georgiades would not be drawn out on Putin’s recent criticism of his country. “We are confident that Cyprus was, and continues to be, an excellent center for financial services, and we are focusing on boosting that comparative advantage,” he told reporters in Nicosia.

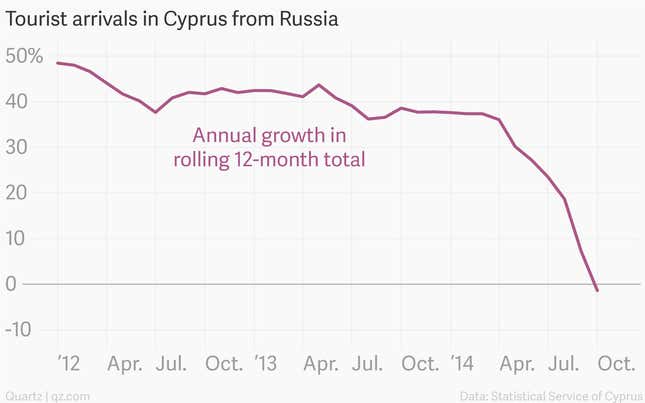

But a worrying sign for Cypriot businesses banking on a renewed Russian influx is a sharp fall in tourist arrivals—the weaker ruble has forced Russians to forgo Mediterranean holidays in recent months, something they didn’t stop doing even after a chunk of their bank accounts on the island was confiscated:

The banks and brokers in Cyprus will be hoping that the drop in Russian tourists won’t foretell a similar drop in Russian funds flowing into the country. But an offshore bank account doesn’t mind if you never visit it, and if the advisers are right about Russians looking to leave their home country, then they will no longer count as tourists in Cyprus—the next time they come to the island, it might be for good.