The Umbrella Movement’s pro-democracy protests have only widened the divide between Hong Kong’s largely pro-Beijing local news coverage and a few pro-democracy media outlets. The protests have also shown that many of the city’s citizens—particularly its digital-native youth—vastly prefer an independent press.

As pro-Beijing factions ramp up self-censorship and pressure journalists to toe the party line, Hong Kong’s next big democracy fight is likely to be over the freedom of the press.

Even before the protests started, the Chinese government lectured Hong Kong’s media on the need to increase coverage of anti-Occupy Central protests (often led by apparently pro-government toadies), while pressuring advertisers who supported pro-democratic publications.As the protests got underway, more than 20 journalists were physically assaulted by anti-Occupy protesters and police.

Free speech isn’t the only consideration—Hong Kong’s media market is also potentially lucrative. Advertising spending in Hong Kong increased 9% in 2013, to $5.56 billion, and about one-third of that went to newspapers and television.

Harassment—and huge traffic—for Apple Daily

By the time the Umbrella Movement began, the Apple Daily, a pro-democracy tabloid, was one of the few local outlets that could boast being fully free of self-censorship or more overt pro-Beijing editorial meddling.

In the two months since, Jimmy Lai, a media tycoon and the tabloid’s editor, was pelted with rotten pig organs and his paper’s delivery trucks were blocked by pro-Beijing demonstrators. On Dec. 10, Lai announced that he was stepping down from his role as editor-in-chief, after being arrested during the clearing of the main protest site.

The paper’s website faced a near-constant onslaught of DDOS attacks—attempts by hackers to take down a site by overloading it with traffic—since the protests began. Mark Simon, a commercial director for the tabloid’s parent company, Next Media, who is often described as Lai’s “right hand man,” told Quartz he was forced to send his wife and kids back to the US after a campaign of harassment by pro-Beijing news outlets. Their photographers were shadowing his family, including his 13-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter, as they went to church and school—even snapping pictures at his son’s baseball game. “They harass you and make your life uncomfortable,” Simon said.

Yet as the protests raged, Apple Daily’s website traffic has been phenomenal, far outstripping any other news outlet in Hong Kong. The most-watched non-music YouTube video in Hong Kong in 2014 was Apple Daily’s live coverage of the protests, which racked up 3.4 million views—equivalent to about half the city’s population.

Whether Apple Daily can translate that traffic into additional advertising revenue remains to be seen—especially since HSBC and other companies have pulled ads from the tabloid under pressure from Beijing.

The SCMP wins readers in HK, but loses in Beijing

The South China Morning Post, historically one of the most respected papers in Asia, also benefited from the protests as its audience grew. The paper has been accused of leaning increasingly Beijing-ward of late. But when the protests began, the newspaper started an outside-the-paywall live blog that offered comprehensive, rigorous, and balanced coverage of the Umbrella Movement unfolded—sometimes in stark contrast with its editorial page’s anti-protest rhetoric.

Some journalists in Hong Kong, both inside and outside the paper, believe that balanced coverage came in part because Wang Xiangwei, SCMP’s editor and a former member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, was on vacation when the protests began. Wang told Quartz he was insulted by the insinuation. “I have been deeply involved in SCMP’s excellent coverage on Occupy no matter where I am,” he said.

Umbrella Movement coverage helped the SCMP’s website hit a traffic record for the month of September, and its daily unique visitors sometimes tripled as the protests got underway. The paper also added 50,000 Twitter followers in the first week of the protests, according to an internal memo distributed to staff.

But the SCMP’s protest coverage rattled Beijing: the SCMP’s Chinese-language site, Nanzao.com, has been blocked in mainland China since the protests began. On the mainland, Hong Kong protest coverage was first censored entirely, and then focused only on the problems the protests caused, and the SCMP’s comprehensive outlook didn’t fit the approved storyline.

Anti-protester coverage was also doled out by pro-Beijing Hong Kong papers like the Oriental Daily. Given other options, the Hong Kong’s residents decided to mostly ignore these news outlets. Here’s a newsstand on October 3:

The public no longer likes public TV

Hong Kong’s state-run station TVB is the main free source of television news in the city, but its Beijing-friendly stance has earned it the nickname “CCTVB”— a play on the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV. The protests brought the issue to a head: after TVB edited out details from its report on a videotaped police attack on a protester, 57 of its journalists risked their jobs by signing a letter of protest. Hundreds of viewers reportedly lodged complaints about what they considered to be TVB’s biased and inaccurate protest coverage.

The station’s stance may also be costing it viewers—TVB’s annual “gala” broadcast last month had the lowest ratings in 17 years, and the station is now up against a new online-only television channel that promises not to talk down to Hong Kong’s youth.

Social media and independent websites trump the mainstream news

Blogs and websites that weren’t necessarily focused on hard news before the protests covered them extensively, like Hong Wrong and Coconuts, and often provided more in-depth coverage than mainstream news outlets.

And despite the ominous developments for freedom of the press, the Umbrella Movement was a watershed moment for social media, as protesters flocked to apps and social networks that largely defy the ability of government censors and corporate owners to control the flow of information.

That includes citizen journalism on Twitter and Facebook, widespread use of messaging apps—including those like FireChat that don’t even require an internet connection—and even the re-purposing of apps that weren’t even designed to share news, like Evernote. The huge range of options also made it possible for professional journalists at pro-Beijing outlets to report on the sly.

Hong Kong’s intractable divide

When China regained control of Hong Kong, it vowed in its treaty with Britain to preserve freedom of speech, as enshrined in the region’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law. The language is unambiguous:

Article 27: Hong Kong residents shall have freedom of speech, of the press and of publication; freedom of association, of assembly, of procession and of demonstration; and the right and freedom to form and join trade unions, and to strike.

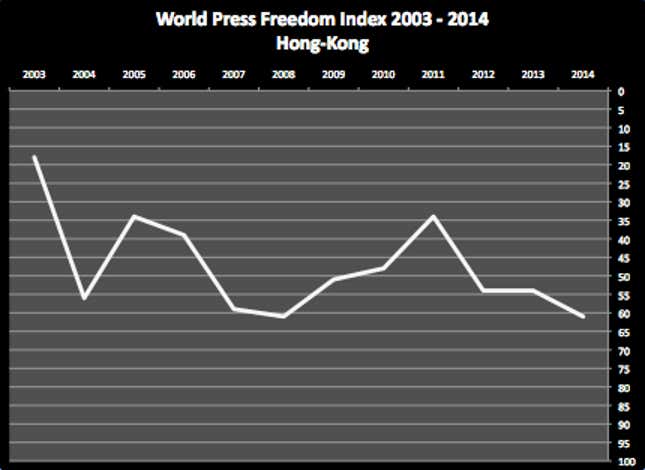

That promise has been undermined in recent years, which have been particularly grim ones for journalistic freedom—the Hong Kong Journalists Association called them the “darkest for press freedom for several decades” (pdf, p.2). And the overall media landscape has indisputably tilted heavily toward pro-Beijing news outlets, even as opposition to the mainland’s encroachment on Hong Kong civil liberties has increased.

Now that the protest encampments have been dismantled, the immediate tensions in Hong Kong may recede for a time. But the fundamental disconnect between Hong Kongers’ demand for unfettered news and the mainstream outlets’ largely pro-Beijing stance will only grow more stark.