Here is more proof, if proof is needed, that it pays to vote.

In Britain, Conservative chancellor George Osborne’s has extended the window to buy government’s “hugely popular” pensioner bonds–to until just after the May general election. The special investments, sold by a state-owned agency, are available only to those aged 65 or older and feature interest rates far above what the open market is offering—4% for a three-year term, while the government can currently borrow for that long at 0.7% in the bond market.

Critics say it amounts to a massive transfer from the young to the old, who are already better off financially. Add that to the government’s “Help to Buy” mortgage subsidy, which was originally intended to benefit first-time homebuyers but has been mainly successful in boosting already frothy house prices—another benefit to older, wealthier people who already own their own homes.

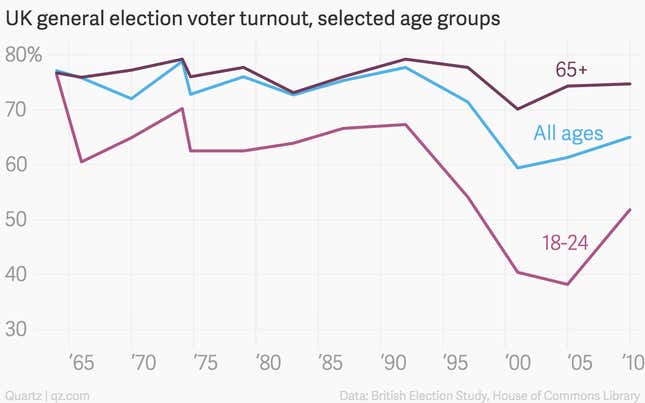

If the economic logic of these moves is puzzling, the political rationale is crystal clear: the old vote, and they often vote Tory.

When they were young, today’s pensioners voted at similar rates to their elders at the time. The apathy and disillusionment that underlies the waning youth vote in the generations since is matched by main parties’ growing indifference to their concerns. These trends seem to feed each other.

The Green Party’s rapid rise among young voters shows how responsive the demographic can be (on paper). The collapse of support for the Liberal Democrats is down, in part, to young voters abandoning the party after it reneged on its pre-election pledge in 2010 to scrap university tuition fees once it joined a coalition government with the Conservatives.

For its part, the Labour Party has aimed its pre-election pledges a bit younger than its Conservative rivals—leader Ed Miliband recently promised to double the minimum length of paternity leave.

But on the issues that the youngest voters care about, like tuition fees, the party’s policy is vague and wishy-washy. It is currently asking young people what they want from the party in an online consultation, with a manifesto based on the results out next month. Meanwhile, more important—and older—target groups are already being showered with (hypothetical) goodies.

In this context, Labour’s pledge to give 16- and 17-year-olds the vote next year, if elected, seems a little strange. On current evidence, this would merely expand the ranks of young voters that it and other big parties ignore.