The UK’s Green Party, so marginal for so long, has seen its membership blossom over the past few months. This popularity is being fuelled by big gains among young voters in particular. And although the Greens will remain a niche party after May’s general election—they currently hold a single seat in parliament, and in the best-case scenario may add only one or two more—the change in sentiment is a sign of broader trends sweeping UK politics, which might play a bigger role in future polls.

Some of this is down to shifts that are taking place across Europe, some to a “perfect storm” in domestic political weather. But a big part of the party’s increasing popularity reflects its policies—many of which are extreme—and how they line up, finally, with parts of the political zeitgeist.

The Greens have remained on the political fringe partly because they were seen as standing for a single issue: the environment. It is indeed central to their policies, but that focus gives rise to a number of radical intentions in other areas, like the economy.

The Greens reject the idea that growth should be a goal, going further than many leftist movements before them, and winning few fans among free marketeers.

The objective, the party says, is to shift economic power towards individuals and households, and away companies and government. It would discourage debt and encourage local economies. A key pillar of the Greens’ economic policy is a “Citizens’ Income,” a benefit paid to every citizen regardless of means, or whether he or she is seeking work.

Born green

These are the things that resonate with younger people. They have been hit hard by austerity and priced out of the housing market, Charlotte George, an Australian film-maker who is running for the Greens in an east London borough, tells Quartz.

Young people have grown up exposed to the idea that the planet’s resources are scarce like no other generation before them. Policies that appeal both to environmentalism and address economic unease seem to be a winning combination for the Greens, at least according to polls.

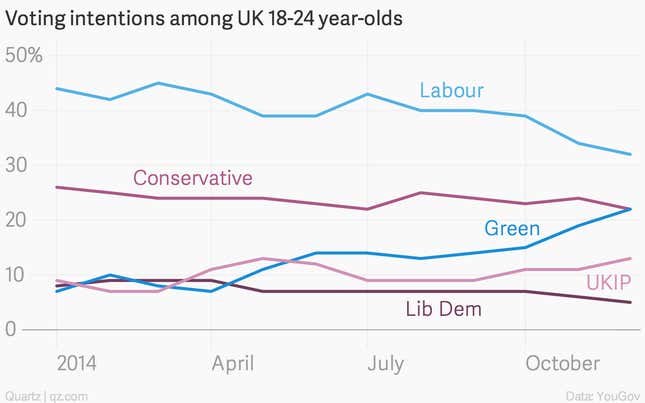

Indeed, over the course of 2014, the Greens have made big gains in surveys of young people. Among 18-24 year-olds, the Green Party surpassed the Liberal Democrats in April, and the UK Independence Party (UKIP) a few weeks later. In December, polls put them neck and neck with the Conservatives among this group of voters:

Other Green policies are less easy to categorize. The party is in favour of a referendum on the UK’s membership in the European Union, the key plank of rightwing UKIP’s platform, and one that the Conservatives are also campaigning on.

The Green Party would also decriminalize membership of terrorist organizations. It would ban zoos. It would legalize cannabis. It would abolish the monarchy.

Eye of the storm

Policies aside, the party’s recent gains are down, in part, to it riding an anti-establishment wave that began elsewhere. Across Europe, protest parties on both the left and right have been gaining strength—most notably in Greece. Closer to home, the Greens don’t like to credit UKIP with some of their success, but they must: UKIP’s rise “shook Westminster,” says George. It proved that the status quo wasn’t unassailable.

The second element of the “storm” propelling the Greens was Scotland’s September 2014 vote on whether to stay in the UK. The vote to remain part of the union was close, and for the first time in Britain, 16 and 17 year olds were able to vote. This energized the younger parts of the electorate, showing them that they were masters of their own destiny (and can stick it to the established order if they want to).

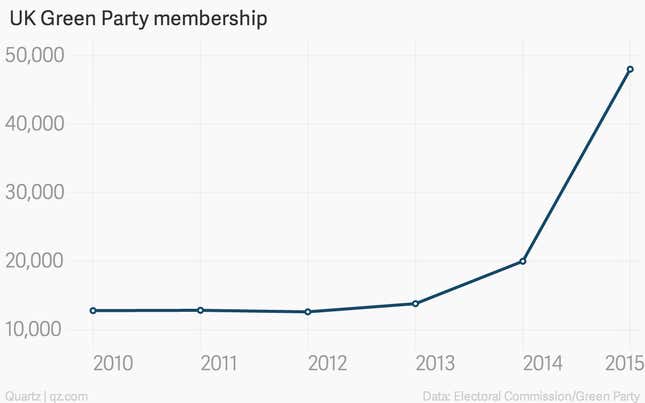

The Greens have also benefited from the debate about what defines a “major” political party, after a regulator ruled that the Green Party did not qualify for inclusion in pre-election debates, while UKIP did. The Greens saw their membership soar over the course of the debate, essentially confirming its status as a force. Green leader Natalie Bennett was recently allowed to join the upcoming debates. “The irony of it is extraordinary,” said George.

Both the left- and right-leaning press in the UK have focused on how the Green surge seems bad for Labour, threatening to split the leftist vote in marginal seats, thereby handing victories to the Conservatives. (The UK’s winner-take-all electoral system does not favor small parties, as it’s only the number of seats won, and not total votes accrued, that matters.)

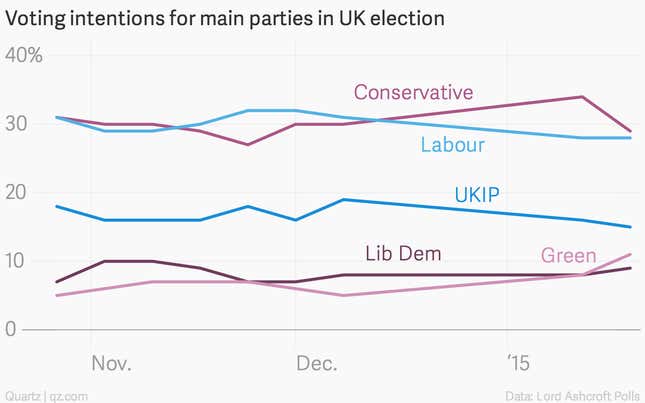

Although the Greens are ascendant, they won’t come close to winning the election in May. Among all voters, they currently sit in fourth place in the polls, behind UKIP but ahead of the Lib Dems, the junior partner in the coalition government.

But what the Greens have already accomplished is a victory of sorts, having succeeded in getting and keeping certain items on the broader political agenda, such as the opposition to nuclear armaments that has been a focus for Caroline Lucas, the party’s sole MP. And this year’s protest vote could be a sign of even stronger support in the future. Or, it could reflect a unique confluence of events and factors that briefly thrust a marginal party to the fore, only for it to fade back to obscurity.