Late last year, Apple’s public relations gurus released “a message from Tim Cook about Apple’s commitment to your privacy.” The post explained Apple’s policies and its inner workings. But it was also a sales pitch:

Our business model is very straightforward: We sell great products. We don’t build a profile based on your email content or web browsing habits to sell to advertisers. We don’t “monetize” the information you store on your iPhone or in iCloud. And we don’t read your email or your messages to get information to market to you.

For years, conventional wisdom has had it that people just don’t care about privacy online. Mark Zuckerberg famously declared back in 2010 that privacy was no longer a social norm. Similar sentiments continue to find their way into the headlines, including at this publication. But various pieces of research have shown the very opposite.

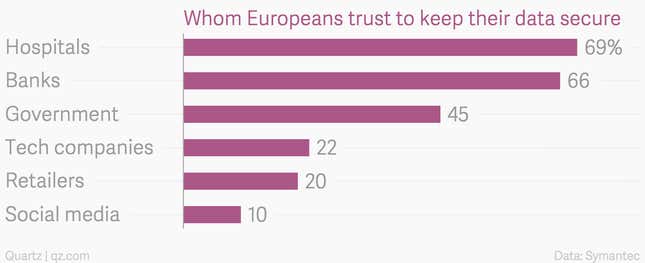

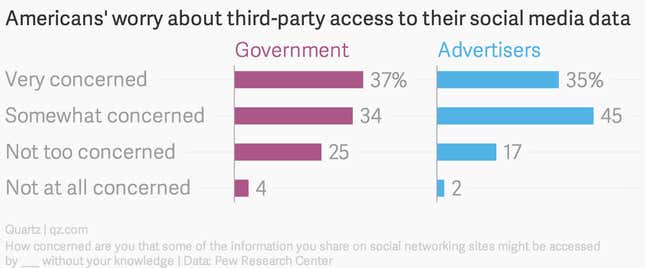

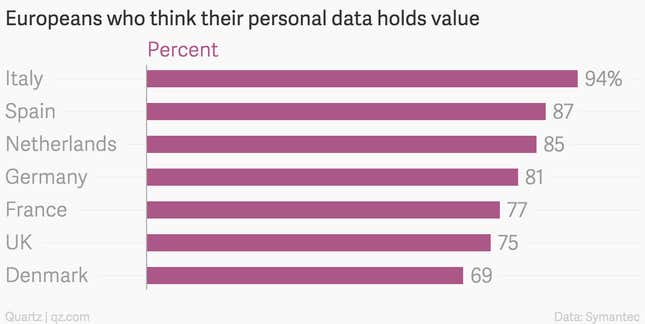

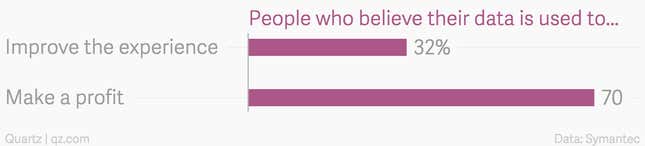

A Pew survey in November found that 80% of Americans are concerned about advertisers gaining access to their social media data; 61% said they would like to do more to keep their data secure. A survey of 7,000 Europeans (pdf) recently released by Symantec (a security firm, granted) found that 66% of respondents want to protect their personal information better but don’t know how.

Nearly two years after revelations about government snooping turned privacy into front-page news, there remains little doubt that privacy is something people care about. Witness the debate in Europe over the “right to be forgotten,” or the developments that led the United Nations to reaffirm “the right to privacy in the digital age.” Consider that this summer, a major exhibition at the Victoria and Albert museum in London will investigate the interplay between public and private.

Some tech firms, like Apple, are starting to see the value in touting their privacy credentials. Others are building businesses on it.

The giants rush in

AT&T, an American internet service provider, found itself in the news (paywall) in February for selling two types of connections: one that tracks subscribers’ online activities in order to better tailor ads for them and another that does not—but costs $29 more. For the basic, $70 plan, that’s a premium of more than 40%.

AT&T has offered the choice for well over a year. “The vast majority [of customers] have elected to opt in to the ad-supported model,” says an AT&T spokesperson.

The thrifty are probably getting the better end of the deal. Customers who sign up to the more expensive plan are only safeguarding their information from AT&T’s advertisers. Facebook, Google, and everybody else can still help themselves. But the $30 premium indicates just how much internet users’ data is worth to the companies mining it.

In November, Google launched Contributor, which allows people to pay for online content in order to avoid ads. Google says information collected when users of Contributor visit participating sites is “not used to target ads or shared with advertisers.”

In Europe, Telefónica, a mobile operator, is also playing the privacy card. Last year, Telefonica held the first workshop for its new Data Transparency Lab. Titled “Personal Data Transparency and Online Privacy,” the workshop brought together academics and startups to encourage research into online privacy abuses.

“We all have a perception that something is wrong, but now we need to get evidence, get data,” says Jose Luis Agúndez of Telefónica’s big-data business. That’s pretty rich coming from someone who works in data for a mobile operator. But Agundez argues that this is why the lab’s work will be done by academic researchers at universities. Telefonica is issuing grants of €50,000 ($56,000) apiece to 10 researchers at universities around the world.

There’s no venture capital without fire

Startups are catching onto the trend, too. Abine, a privacy company, bills its Blur service as an “all-in-one solution for managing your online life and protecting your private information.” The firm promises to mask your email (essentially your passport around the web), encrypt passwords, and block trackers. For $39 a month, it also will hide your credit-card details and provide temporary phone numbers. Rob Shavell, Blur’s CEO, believes that there is an opportunity to create a billion-dollar company in privacy.

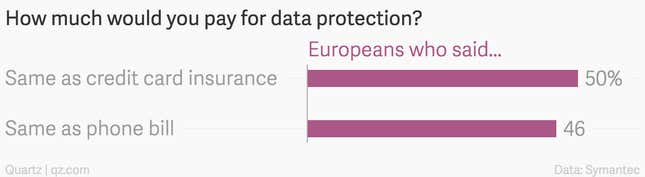

Indeed, he argues that privacy already is a billion-dollar business. Sizing the market for privacy is hard because “privacy” is a squishy term. But, he says, look at virtual private networks (VPNs), which allow people to mask their internet addresses, or domain registrations, where companies charge registrants a few dollars extra to mask their names and addresses. It is clear that people are willing to pay for privacy. But VPN users and domain name registrants are technically proficient. Can everyday consumers be persuaded to pay?

The answer remains unclear, but venture capitalists sniff opportunity: Wickr, an encrypted messenger service, has raised nearly $40 million. Dashlane, which helps users encrypt data, has raised $30 million. Disconnect blocks third-party trackers and has received $4 million in funding. The aforementioned Abine has received $6.5 million.

Perhaps the most telling—and most valuable—example of a consumer privacy company is Snapchat, which is said to be seeking a $19 billion valuation. Snapchat does not bill itself as a privacy company and has in fact been charged with being slack on user privacy. But it is hard to argue that the appeal of its disappearing messages service does not arise from the illusion of privacy it offers users.

Not the only way

The lure of customer data and opportunities to exploit it is a strong one. Indeed, invading privacy has been baked into the very business model of the web in our present era.

For a company to receive high valuations and massive funding rounds, it needs to show a large and growing number of users. Once it has those users, it needs to start making money. The default option—since it would be difficult to convince several hundred million people to pay for social networking, for example—is to advertise to them. The promise of internet advertising is targeting and measurement. To achieve that, a company needs to know what its users want and what they do online. And so it goes.

But that is not the only way. Whatsapp, which Facebook bought for $19 billion in 2014, has promised not to collect user data or sell advertising. Snapchat’s first attempt at making money is to tie up with publishers. There are other ways to make money online besides advertising.

Ghosts in the machine

One of those ways is to help advertisers. That’s how Ghostery, a privacy tool, keeps itself afloat. Some 40 million people use Ghostery, a browser extension that blocks trackers, beacons, analytics, and other assorted widgets. Any website—say, qz.com—loads some of the page from its own server and some of it others. Ads that come from ad servers are blocked.

But other elements, such as the Facebook “like” button are also blocked: the button is sent to your machine by Facebook, not by the website you visit. That button allows Facebook to gain access to the data your computer automatically gives up when it loads a site. Ghostery blocks all of these third-party elements. Objective Development, an Austrian company, charges €29.95 ($33) for a similar product, called Little Snitch.

Ghostery provides its software to users at no cost. It makes its money by tracking the trackers on websites visited by users who have opted in, and using that data to tell companies what junk has accumulated on their sites. A single tracker often calls in other trackers—as a result, websites are sometimes cluttered with several dozen of these external elements they do not know about. Ghostery tells them what they are and how they’re slowing down the site, and charges for the service. It is a business that both protects user privacy and helps businesses. Scott Meyer, Ghostery’s CEO, says the company is growing 6% to 7% every month.