The watch industry first giggled at the Apple Watch. Now, it is racing to catch up.

Today at a watch expo in Switzerland, Tag Heuer—owned by the LVMH luxury conglomerate—announced a smartwatch collaboration with Google and Intel. And Gucci, the Italian luxury house, unveiled a partnership with the musician Will.i.am to develop “an innovative concept in terms of wearable technology”—one that already looks passé.

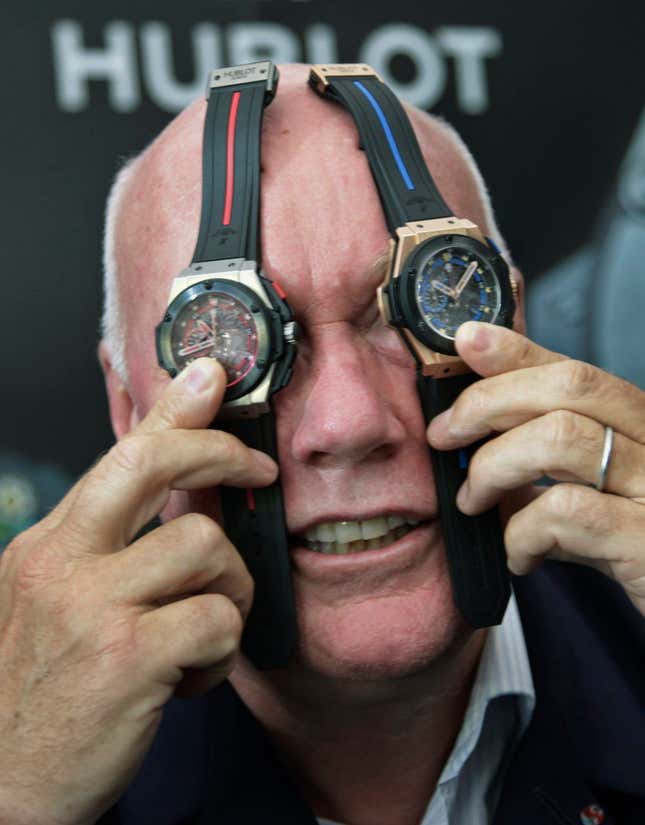

In his announcement at the Baselworld watch expo today, LVMH watches chief Jean-Claude Biver said this was his “biggest announcement ever” in his 40 years of working in the industry. He predicted the device would be the “greatest connected watch.”

“The difference between the TAG Heuer watch and the Apple watch is very important,” Biver said. “That one is called Apple and this one is called TAG Heuer.”

The problem is, it’s not that simple. While the Apple Watch looks like a watch, it’s not actually a watch.

If the Apple Watch is a hit, it won’t be because Apple is winning over would-be Tag Heuer or Rolex customers. It’ll be because Apple will have convinced tens of millions of people to wear tiny computers on their wrists. Those people will then have no need for “watches.” Apple has some work to do here—most people are still far from convinced that they need one of these things, and the design could be thinner and prettier. But it’s starting strong.

Meanwhile, there’s no reason to believe that the people who buy Tag Heuer watches for their craftsmanship have any interest in tracking their fitness or getting text message notifications on their horological heirlooms. And if you’re buying a classic mechanical watch, it’s supposed to last forever, to be passed down to your offspring—not to go obsolete after a couple of years.

(It is possible, we suppose, that Tag Heuer could somehow teach itself to become the world’s foremost wrist-computer company—and leapfrog Apple—by next year. But that seems extremely unlikely. Apple didn’t just take a heritage watch case, add a screen, and shove in a microchip and a bunch of sensors. And as Biver is about to discover, trying to integrate one company’s microchip with another’s operating system and app ecosystem, then reconciling that combination with your company’s century-old design ideals is going to require some major compromises.)

Ironically, if the Apple Watch is successful—and has any negative impact in Switzerland—it will be because Apple as a company follows the same tight, vertical integration that the Swiss watch industry does for its core product, mechanical watches.

Since the 1990s, watch companies “have been making increasing efforts to in-source as many steps in the production process as possible,” ranging from individual watch components to retail distribution, according to a Credit Suisse report on the Swiss watch industry. “The manufacturers’ objective is to have the greatest possible control over the entire value chain and to decrease their dependence on external suppliers.”

This is precisely the model Apple has followed, too, designing everything from its microchips and manufacturing processes to its operating systems and retail stores. And that has helped it grow to become the most valuable company in the world.

Now, just as Apple is entering the watch business, the Swiss-led watch industry has to break the habit that brought it success, and look outside for help. This is hardly the time for the arrogance that Biver’s tone imparts.