In London and Paris, two recent construction projects have been held up for macabre reasons: hundreds or thousands of centuries-old bodies buried in the ground beneath.

Excavations of these mass graves have delayed a new train ticket hall in London and a supermarket development in Paris, pointing to how often construction on a crowded and rapidly modernizing continent involves encounters with the dead.

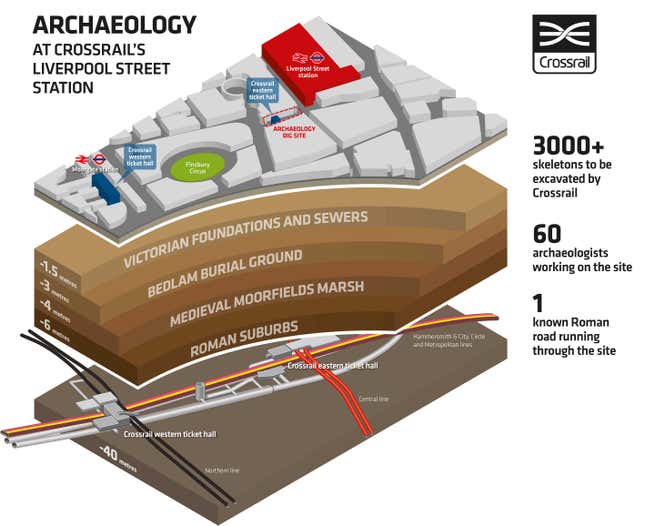

In London, a city of layers, past generations have lived, died, been buried–and then built upon.

Building work for a high-speed rail line called Crossrail uncovered 3,000 skeletons from the Bedlam burial ground, near Liverpool Street Station in the business district.

The newly-uncovered graveyard was used for victims of the city’s several plagues. The last “Great Plague” struck the city in 1665 (finally wiped out by the Great Fire of London a year later). After 350 years, archaeologists on the Bedlam dig hope testing excavated victims will help them study the disease.

From the 1560s until the 1730s the pits were used for those who couldn’t afford church burial, or weren’t accommodated in the overflowing cemeteries. Bedlam, a corruption of the word Bethlehem, was most famously an asylum for those deemed to be lunatic.

The problem of construction bringing the dead to light also plagues France. Last month, a Monoprix supermarket in Réaumur-Sébastopol, Paris, had to close temporarily while 200 skeletons, packed in tight, neat rows, were excavated from beneath it.

Cataphiles–urban explorers who break into Paris’s underground network of tunnels–know that human remains could once often be found there; though most have now been either taken as trophies or collected together in macabre skull-stacks and bone walls in the official tourist attraction section of the network.

Back in London, building work for the new offices of the media company Bloomberg uncovered so many artifacts that the firm is incorporating a museum into its plans, to house them.

The digging up of graves and re-burying of remains has been fascinating the British in recent months. The hunt for King Richard III’s bones eventually led to the successful excavation of a car park, and to an elaborate series of reinterment ceremonies for the ancient, battle-hacked skeleton.