The Greek government might run out of money in two weeks. Or perhaps four. Capital controls are either imminent or a month away. Whatever the case, depositors are draining Greek banks dry, which could hasten a state default and, potentially, ejection from the euro zone altogether.

The four-month bailout extension that Greece got in February now seems a distant memory, with €7.2 billion ($7.8 billion) in much-needed funds still contingent on Greece drawing up a detailed list of reforms, which creditors are vetting this weekend. If they don’t like what they see, it might mark the beginning of the end for Greece’s membership in the euro.

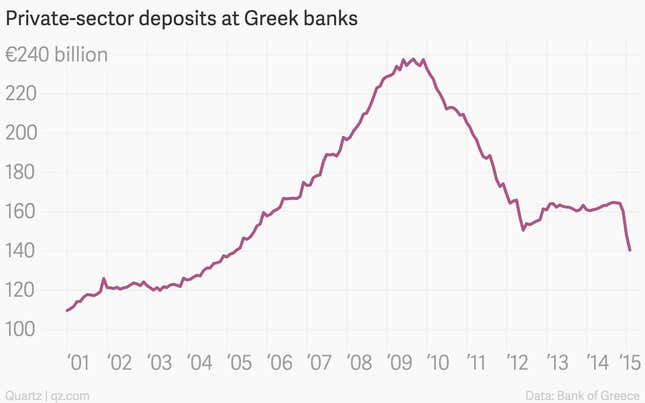

This fear is what’s driving the outflow of deposits at Greek banks—the private sector withdrew more than €7 billion in cash last month, pushing deposits to a 10-year low:

But there is “no panic,” according to a senior Athens-based banker. The outflows in 2012 were scarier, the executive tells Quartz, because nervous Greeks squirrelled their cash abroad, whereas it’s now mostly staying in the country—“under mattresses”—and can return quickly once the country’s financial future becomes clearer.

An agreement to release funds pledged by the bailout extension should come next week, the banker believes. Then, a longer-term bailout deal worth perhaps €30 billion can be agreed. But this confidence stems in part on creditors committing to the sunk cost of some €240 billion in funds that they’ve already committed to Greece.

It is equally wishful thinking, perhaps, for Greece’s leftwing government, led by prime minister Alexis Tsipras, to renege on some of its pre-election pledges to get these deals done with its exasperated lenders.

The government is long on rhetoric but short on experience, as seen by the performance Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s economics-professor-turned-finance-minister, which “leaves a lot to be desired,” according to the banker.

The controversial finance minister has recently cancelled appearances abroad to focus on the negotiations with creditors. Despite diplomatic missteps, particularly with his German counterparts, Varoufakis will put the necessary work in to keep Greece solvent and in the euro zone, the bank executive says. But a lack of political experience and ambitions makes him “expendable,” which can be useful—Varoufakis “can raise the heat of negotiation, and then step down.”

Indeed, rumors the finance minister was planning to resign were batted down recently. There is an air of an endgame to this Greek saga, but there is still plenty of scope for drama and, potentially, tragedy.