If you’ve seen The Wolf of Wall Street, you know having too much money can be a problem. And too much money is part of the predicament that the world economy finds itself in right now.

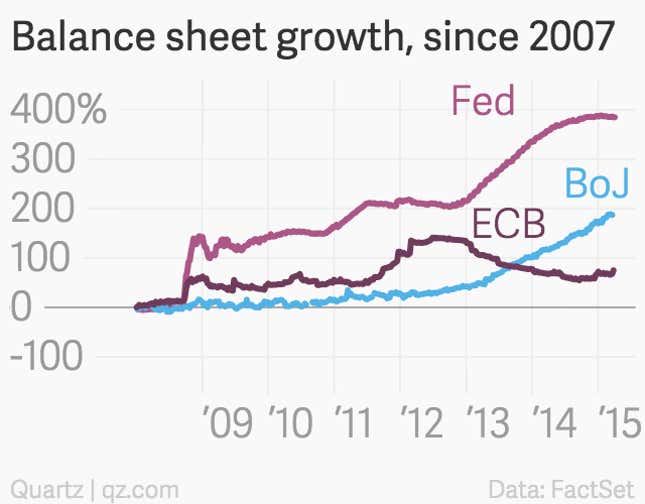

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the world’s most important central banks embarked on a program of pumping out billions in freshly created money. Though the US Federal Reserve has turned off the spigot, the deluge continues. The Bank of Japan is in the midst of a giant push to churn out yen. And belatedly the European Central Bank has just started, and likely will have to continue generating new euros for years.

This was, of course, the right thing to do. The US economy is in the best shape of any of the large, developed countries, thanks in no small part to the aggressive actions of the US central bank. And while the jury is still out on whether Japan’s push will be effective, the ECB’s effort already seems to be bearing a bit of fruit. (Unemployment is finally falling, albeit slowly.)

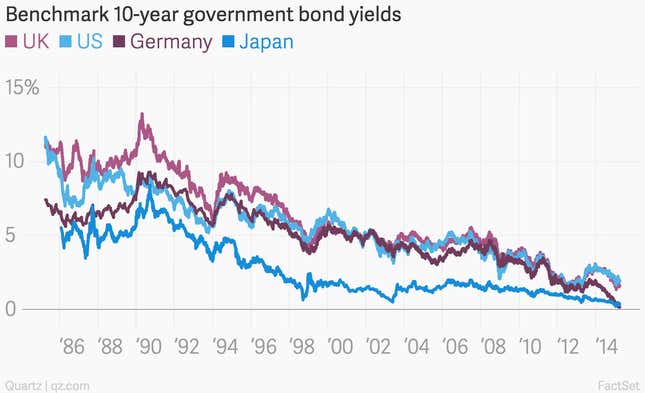

But the aggressive action hasn’t been good enough. How do we know? Interest rates. Global interest rates remain ridiculously low. (One way to think about interest rates is that that they’re essentially the price of money, that is, where supply meets demand.)

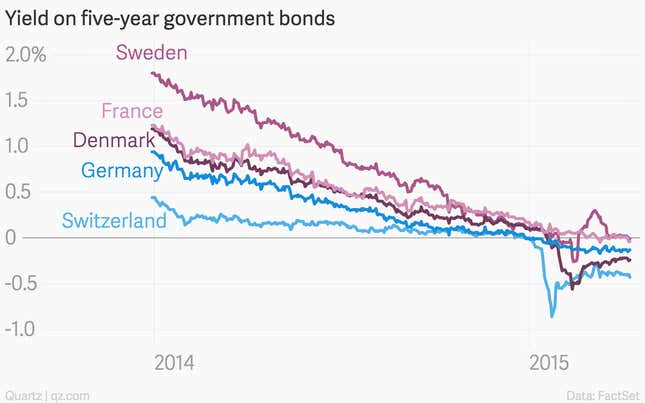

In some cases, they’re lower than low. They’re negative. This week Switzerland became the first country to sell 10-year government bonds with a negative interest rate. That means that at the end of 10 years, investors will get less money back than they lent to the Swiss. And Switzerland is not alone—interest rates are negative for a range of government bonds, especially in Europe.

Remember, interest rates are one price for money. And prices are determined by supply and demand. We’ve already talked about the supply. There’s a lot, thanks to central bank money printing.

Demand? Not so much. Investors don’t seem to want to invest in a global economy that doesn’t look so hot. China is slowing. Europe is barely puttering forward. South American giant Brazil looks horrible. Russia looks even worse. Nobody expects much from Japan.

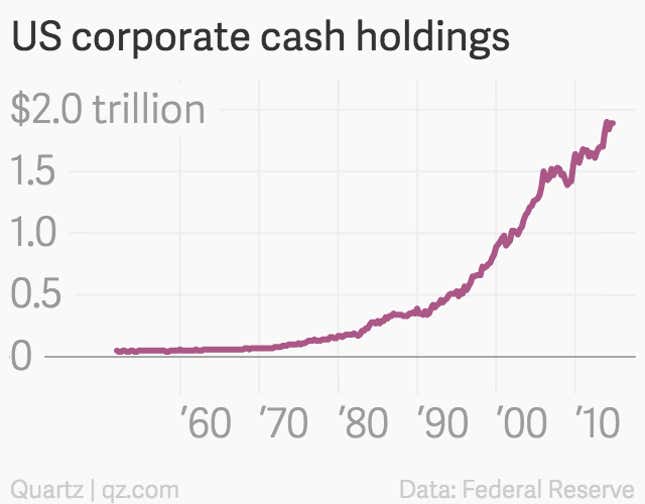

The US is the best banana in the bunch. But even American companies—which have a ton of cash—don’t seem particularly willing to do too much productive investment. Just look at one of America’s greatest blue chip companies, General Electric. The industrial giant said on April 10 that it would return $90 billion to shareholders through a series of dividends and share buybacks. And in order to return that money to shareholders, GE is going to repatriate some of it from foreign countries, racking up what could be a $4 billion tax bill. CEOs are loathe to fork money over to the taxman. If paying taxes is a corporation’s idea of efficient use of capital, then the company is running out of ideas.

There are any number of ways to describe the current status quo. Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has been pushing the idea that the global economy is in the midst of a “secular stagnation.” Summers draws on the work of American economist Alvin Hansen—who coined the phrased “secular stagnation” during the Great Depression—to argue that a persistent excess of savings over investment was due to a slowdown in demographic and technological development.

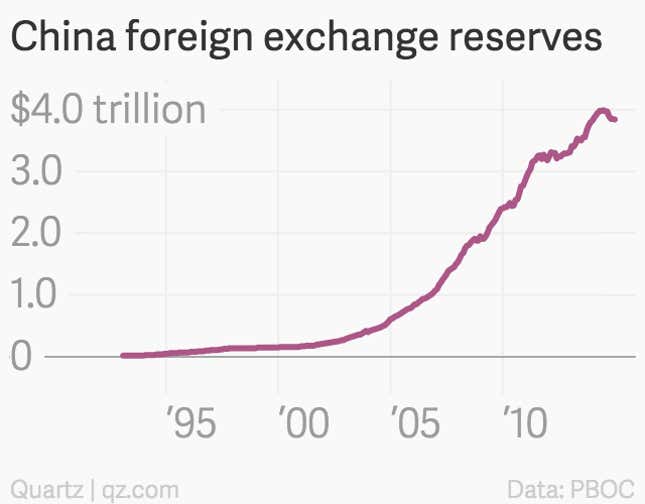

Former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke casts the situation as a “global savings glut,” an idea he first posited in the 1990s. Put roughly, the idea here is that foreign governments—specifically in developing economies that were freaked out by the currency crises of the late 1990s—have been hoarding dollars. They use their dollars to buy super safe government bonds. Those bond purchases are part of the reason why interest rates are low.

Who’s right? It doesn’t really matter. The facts on the ground are the same. There’s too much money and not a lot to do with it. And that’s why we’re seeing investors make some interesting, seemingly non-economic decisions with their piles of cash.

For instance, China is one of the key countries racking up dollar reserves and contributing to ex-chairman Bernanke’s savings glut. But China also is a victim of the low interest rates that the glut has helped create. That’s because there are very few places for China to put any of its dollars for safe-keeping that will earn much of a yield over time.

So instead, China seems to be putting the money to political use, using its giant pile of reserves to help finance the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a Chinese-led rival to the western-dominated IMF and World Bank.

Governments around the world would do well to follow China’s lead. With corporate investment weak, it now falls to governments to spend more, on long-term investments that can boost productivity and give the economy a nudge. Germany certainly has the wherewithal to undertake such a program. And thanks to super low interest rates, many others can, too—including the United States.

Governments around the world have been hoping that aggressive money-printing policies from central banks could get the global economy fully up-to-speed again. It hasn’t happened. Essentially, the free ride is over. Governments need to start contributing.