The UK general election is tomorrow, and the consensus is that there’s unlikely to be a consensus. Many pollsters have the two main parties, Labour and the Conservatives, about even on around 34% of the vote each.

Given the UK’s electoral quirks, this will translate into a larger share of parliament’s 650 seats. But neither party is expected to win anything close to a majority on its own, nor be able to form a majority coalition with smaller parties that share similar ideologies.

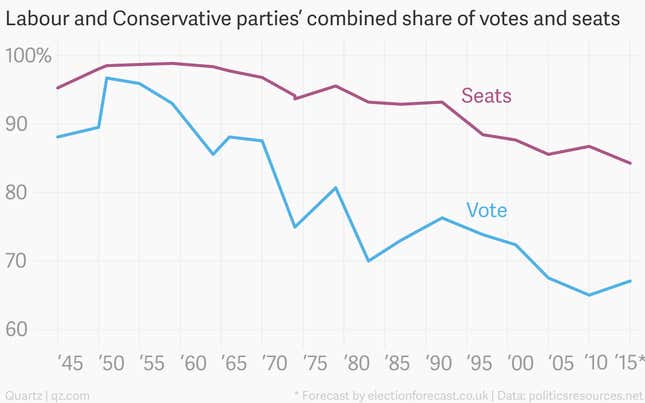

For decades, Labour and the Conservatives could regularly count on winning more than 90% of parliament’s seats between them. But this share has been falling, and is set to reach its lowest point in a long time:

In 2010, the Conservatives won 47% of the seats, and went into coalition with the Liberal Democrats to achieve a majority, the UK’s first formal coalition government since the 1940s. That was rather straightforward compared with the much messier, continental European-style system that seems to be developing, where neither of the two main parties—which the “first past the post” electoral system is designed to keep strong—can ever command a majority without the help of at least one additional party. One of the two main parties may even try to run a minority government—last seen in 1974, in a Labour administration that lasted for just seven months before a fresh election was called.

Whatever the case, voters have shown a growing preference for parties outside of the traditional mainstream, especially in Scotland. And while the Conservatives’ David Cameron and Labour’s Ed Miliband continue to claim that they will win a majority on the day, the polls tell a much different story.