“Outbreaks of political panic are near-certain.” “Europe’s most politically unpredictable country.” ”Literally ungovernable.”

These descriptions could apply to any number of countries—Greece and Spain spring to mind—but Britain normally wouldn’t rank high on the list.

And yet, the UK’s “days as a haven of political, economic stability are numbered,” according to Anatole Kaletsky of Reuters. You can read similar sentiments by number crunchers in the Guardian and pollsters in the Sunday Times.

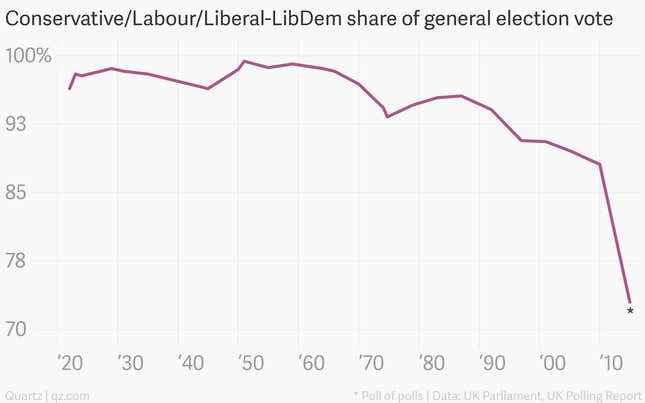

In short, what comes after the UK’s general election in May is anyone’s guess. This is based on variations of this chart, which show that on election day support for the country’s three traditional parties could touch historic lows:

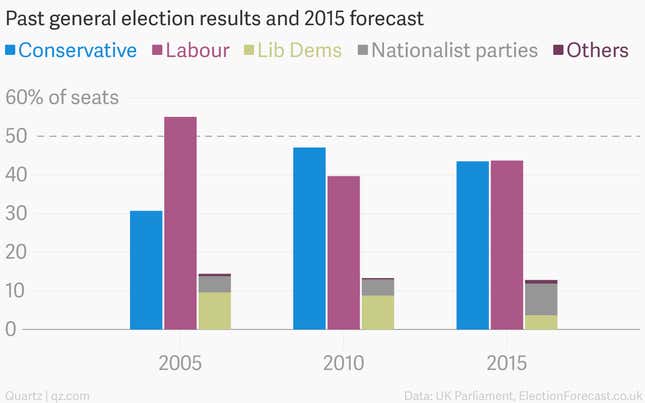

The actual impact on parliamentary seats will be less striking, thanks to the UK’s “first past the post” system, where a narrow plurality in one constituency wins a seat just the same as a large majority in another. But what is becoming clear is that no party next year is likely to win the necessary outright majority (326 out of 650 seats) to govern alone.

The 2010 election that produced a continental-style coalition government was not a one-off—if anything, in the future the current Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition will look downright straightforward compared with what’s in store for 2015 and beyond. Here is the current projection of seats from the professors behind ElectionForecast.co.uk, compared with the previous two elections:

The Conservatives are losing supporters to the right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP), which has already claimed two Tory MP defectors this year. Labour is set for a rout in Scotland, where it could lose several seats to the resurgent Scottish National Party, which is riding a wave of popularity following the narrow defeat on independence earlier this year. The Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, could see supporters turn instead to the Green Party.

Thus, the UK is shifting from a two-party system (with the occasional cameo from the Liberal Democrats) to one where, according to YouGov pollster Peter Kellner, “at least three parties will need to work together in some fashion to provide stable government.”

It might take even more than that. The coalition calculus required to cobble together a majority next year could feature the Conservatives or Labour reaching out to the assorted nationalist parties in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; cajoling the Lib Dems or Greens into a partnership; or even getting into bed with the rabble rousers of UKIP. These fragile structures raise the risk of constant infighting, frequent confidence votes, and regular snap elections.

It all seems so… European. And given that one of the defining issues of the next parliament will be whether the UK should hold a referendum on its continued membership of the European Union—home of all those other rickety multi-party coalition governments—it is also rather ironic.