A funny thing happened to Vine, Twitter’s short-form video app, after its initial buzz wore off: It kept going.

If you haven’t checked lately, Vine, launched in early 2013, is still a thing. It has evolved from a social “Instagram-for-video” built atop Twitter into a unique mobile entertainment platform with its own style, format, and celebrities. And as mobile video continues its long-awaited rise, Vine has built and maintained an impressive audience.

Vine serves more than 100 million people across the web every month, according to the company, delivering more than 1.5 billion “loops”—its term for video views—per day. It is a top-100 free iPhone app in 13 countries, according to App Annie, a service that tracks app stores, and is currently ahead of Tinder and Shazam in the US rankings.

Meanwhile, comScore says Vine reached 34.5 million unique visitors in the US in June across desktop and mobile—roughly the same as Snapchat, which has grown rapidly over the past year and is valued by investors at $16 billion.

Vine owes some of its success to the fact that it is a simple, free video-hosting service that works well with Twitter. Sports and television clips, for example, are hardly special to the app. Just as on YouTube, many are uploaded without permission. But various teams and leagues, including Major League Baseball, are also using Vine to quickly post highlights.

And Vine fits a broader trend. Like Snapchat’s short videos, Vines seem exactly the sort of mobile-native content “snack” that people would watch on a smartphone, or even a smaller-screened device, like an Apple Watch. (Apple used a simple Vine app in a recent Apple Watch keynote demo.)

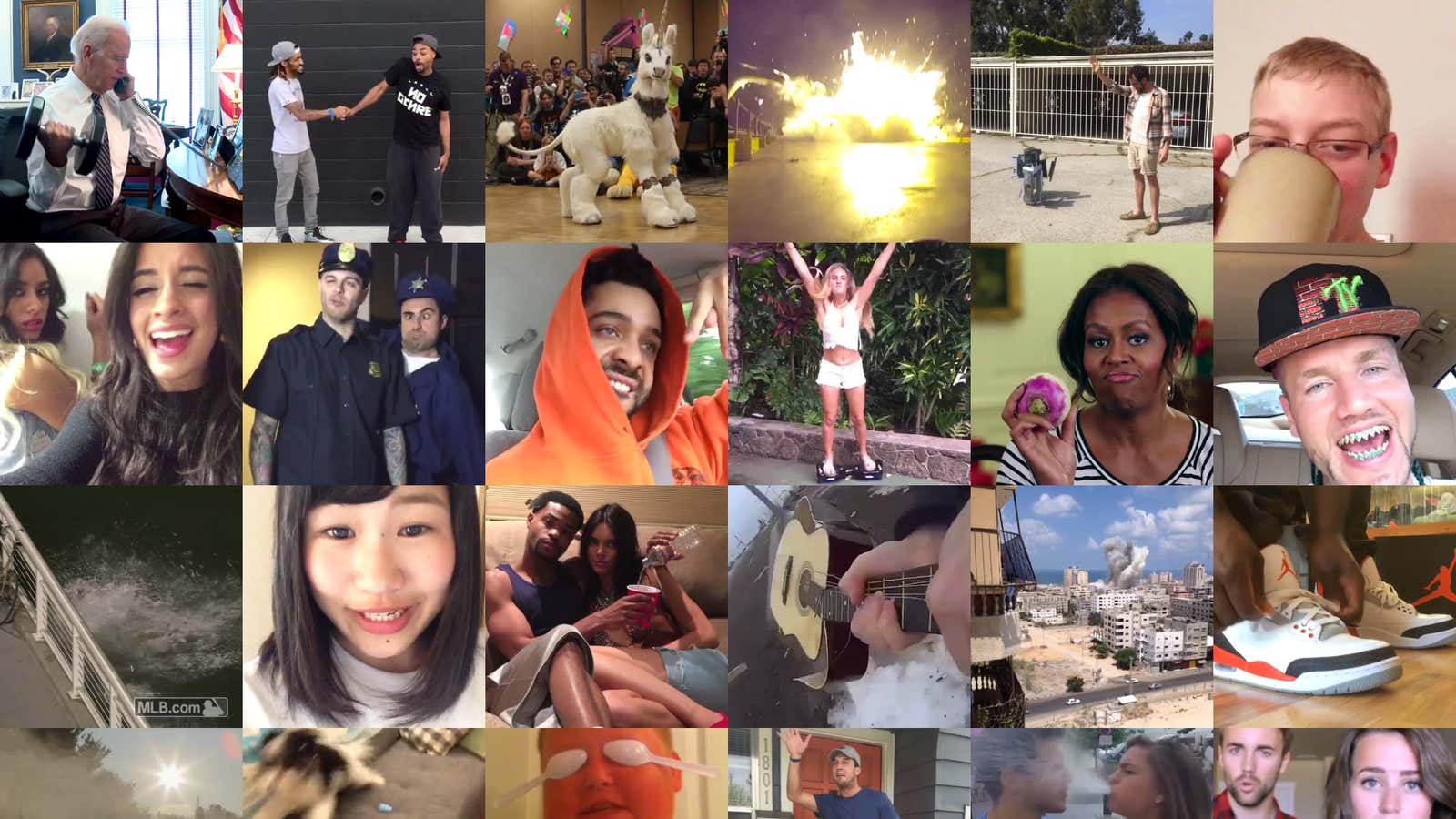

But what’s most interesting is the homegrown group of “Viners” that has developed. These mostly young creative-types produce an enviable stream of short videos, ranging from the artistic and musical to one-liner, sketch-comedy-like micro-skits. The top personalities are wildly popular, tend to collaborate with and reference each other often, and have come to define a big part of the service.

These include Lele Pons (above), the only Viner with more than 6 billion cumulative loops; KingBach, whose Vine-native slapstick often satirizes relationships and money; and Logan Paul, whose recent profile on Tech Insider starts with a shirtless photo in his Los Angeles apartment, standing next to a boom mic. “I want to be the biggest entertainer in the world,” Paul told the reporter.

Like early YouTube stars, you wouldn’t have known their names before. But each typically generates millions of views and thousands of comments when they post.

While Vine doesn’t directly generate any revenue—and has no current plans to—it has become a playground for these creators, who sell their popularity to brands in the form of sponsored Vines. Twitter, to its credit, has considered this. Many of these deals are now brokered by a talent agency of sorts called Niche, which Twitter acquired earlier this year.

Another cool thing: Any random Vine can go viral, aided by Vine’s recirculation features and, likely, its connection to Twitter. After one teen user, Kayla “Peaches Monroee” Newman, posted a video last June noting that her eyebrows were “on fleek,” the phrase spread rapidly on Twitter and throughout society, referenced by IHOP, Taco Bell, and Kim Kardashian.

“It’s not just about shouting into a dark hole,” Jason Mante, Vine’s head of user experience, tells Quartz. “People are putting themselves on Vine—and putting content and ideas and stories onto Vine—knowing that there’s so much potential for millions of people to see this thing.”

Yet Vine, which has about 40 staffers, isn’t often mentioned when parent-company Twitter describes its plans—a topic of increasingly frequent discussion.

Twitter, whose stock price has declined almost 50% since April, now finds itself in an unenviable position. It must re-accelerate audience growth and rethink its product for a broader market, while also undergoing an awkward, public CEO transition.

On its most recent earnings call, where co-founder and interim CEO Jack Dorsey began to lay out Twitter’s strategy, Vine was only mentioned in passing. More attention seems to be going to Periscope, a live-video-streaming startup that Twitter acquired and launched earlier this year.

And this makes sense. As Twitter tries to promote itself as a platform for global discussion around live events, the real-time nature of Periscope seems a closer fit than Vine, where the most popular videos tend to involve planning, props, and editing.

To its credit, Twitter hasn’t ruined Vine—which runs as a separate company within Twitter’s New York offices—the way many big companies botch acquisitions. A Twitter rep, asked by Quartz whether the company plans to continue to invest in and support Vine, said, “We do!” And Vine has a dozen different job openings listed, from iOS engineer and “music content strategist” to head of product.

So why don’t you hear more about Vine? One reason, perhaps, is that you’re reading highbrow, global business news publications instead of lad mags.

But Vine is also in a somewhat strange position: It is a small, comfortably financed startup within a large organization. It doesn’t have a mercurial, fameballing founder at the helm. (Its co-founder and former general manager Dom Hoffman left a long time ago.) Nor is it in the business of gloating about its stats to raise venture capital at increasingly high valuations.

While some of that pressure can be helpful (and fun) to keep growth top-of-mind, this setup gives Vine an opportunity to focus on building tools and audience for its community of creators and fans—assuming they don’t bail for the next flashy new thing.