Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook founder and CEO, is fast becoming the world’s most prominent China nerd. He meets with the Chinese president, reads Chinese science fiction, and of course, is very publicly trying to master Mandarin.

Now Zuck has taken it a step further by delivering a 20-minute-long speech, entirely in Mandarin, to Tsinghua University in Beijing.

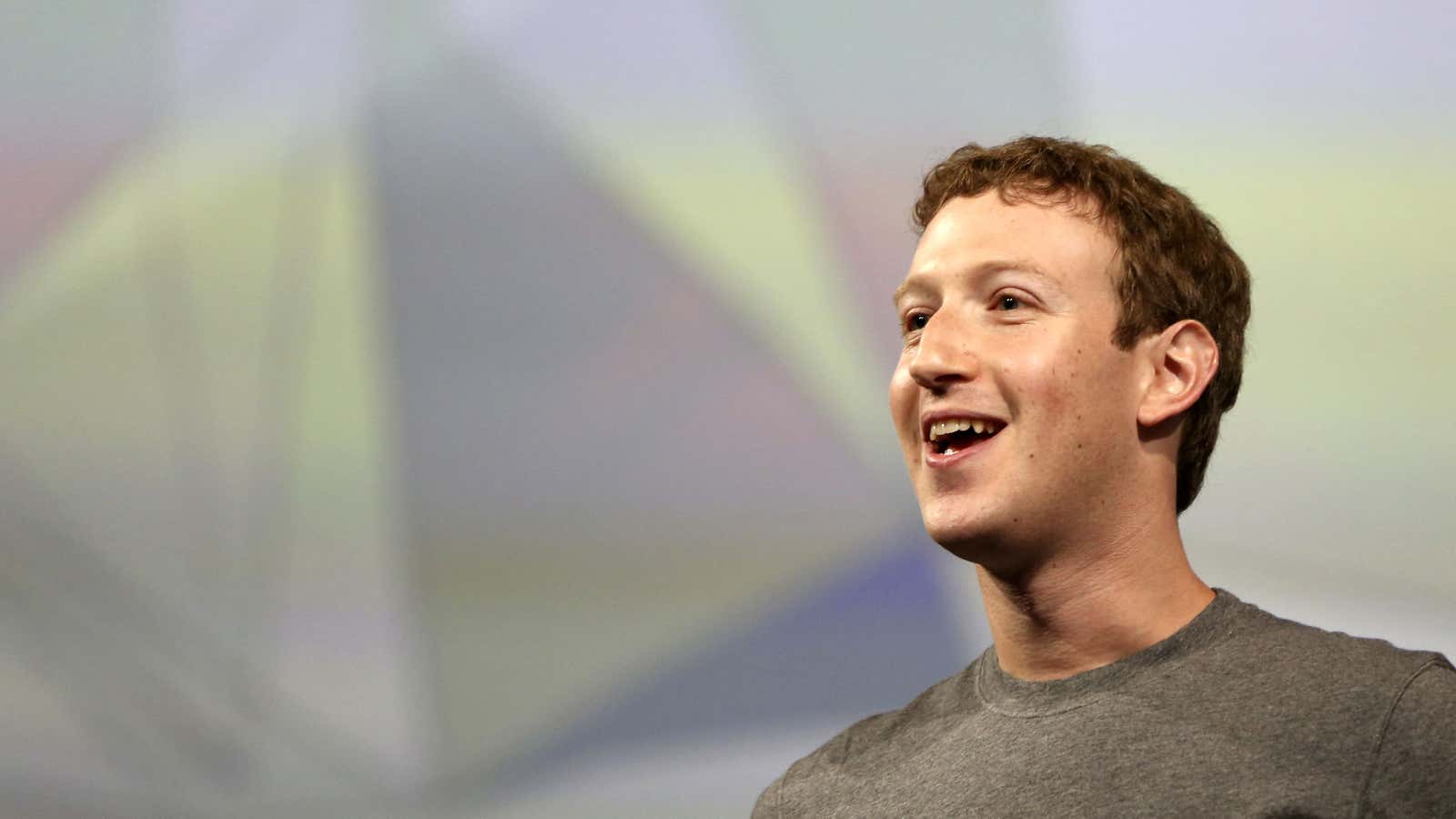

Armed only with a gray t-shirt, a few years of language study, and what appear to be some vocabulary notes on a screen near the floor, Zuckerberg bravely, awkwardly wrestles with Mandarin to discuss Facebook’s origin story, and his belief that a company must have a strong sense of mission. The speech comes one year after he did a 30-minute Q&A, also at Tsinghua, where he sits on the board of the School of Economics and Management.

Here is the full speech, with English subtitles:

Two things you may be wondering at this point: First, is Zuckerberg’s Mandarin any good? Second, why does he care so much about a country that actively blocks Facebook? We have the answers.

How good is Zuckerberg’s Mandarin?

Zuckerberg clearly exhibits the qualities most important in a successful language learner: solid work ethic, acceptance of inevitable mistakes, and irrational audacity. (It bears mentioning that these are not unlike the qualities of a successful startup founder.)

After last year’s Q&A at Tsinghua, we said that Zuckerberg’s enunciation “was roughly on par with the clarity possible when someone’s stepping on your face.” Since then Zuck has made impressive strides, particularly in vocabulary and grammar.

But his pronunciation remains a major problem, now roughly on par with the clarity possible when someone’s on a bad Skype connection. His heavy American accent, imprecise use of Mandarin’s tones, and frequent mixing up of similar sounds makes him hard to understand. He frequently mixes up the tone for “heart,” for example, making it sound more like “belief.”

This doesn’t mean his message is totally lost, but the Mandarin speakers at Quartz and many users on Weibo agreed that understanding Zuck requires some extra focus on the part of the listener. And while his usage has improved, he sticks to relatively uncomplicated platitudes like “If you know your mission, you don’t need to know the entire plan,” or “With each step, you can do new things.”

The splash Zuckerberg makes each time he whips out his Mandarin reveals an odd linguistic double standard. If Zuck were learning Spanish, and gave a speech using Spanish with this poor of an accent, he would probably be laughed out of the room or asked to use an interpreter. And it would be hard to imagine a Chinese entrepreneur giving a talk to Harvard students in similarly broken English.

In short, Zuckerberg is a long way from doing the Mandarin equivalent of an interview with Charlie Rose, as Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, gave in English at Davos this year. But he’s well on his way, and appears to be enjoying himself thoroughly.

Isn’t Facebook blocked in China?

Zuckerberg’s sinophilia is also about much more than just communicating in Mandarin: It sends the message that he is all-in on China. During a visit to the US, Chinese president Xi Jinping reportedly spent more time with Zuckerberg (paywall) than he did with other top US CEOs, because the two were talking in Chinese.

And while access to Facebook remains blocked in mainland China, Facebook Inc. has plenty of business opportunities there. Chief among these is Facebook’s ad services. Chinese consumer companies that develop brands for customers globally will want to use Facebook ads to reach customers in new markets. Facebook last year leased office space in Beijing to establish an ad sales office and, possibly, to provide a headquarters for the “thousands” of developers it has there. A year later Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s COO, told a conference in New York that the company’s business in China was “thriving.”

The Facebook-China ties extend well beyond Zuckerberg’s studies. Facebook hosted Lu Wei, China’s internet censorship chief, at its headquarters late last year. Not only did Zuckerberg conveniently leave his copy of The Governance of China, a collection of Xi’s speeches, on his desk for all to see, he said he was suggesting that all of Facebook’s staff read it, too.

Zuckerberg’s charm offensive is resonating in China. State-run news outlets have taken to Facebook, even though their own citizens can’t see their posts, Xi Jinping’s US trip was publicized on the social platform, and Zuckerberg’s appointment to a board at Tsinghua suggests he is trusted by normally wary authorities. Many Weibo users said they were “moved” (link in Chinese) by his speech in Mandarin, even if they couldn’t understand all of it.

But even with all of this, it remains unlikely that the government will unblock access to Facebook too unless it, like some other US internet companies, agrees to conform to China’s strict censorship rules.