We’ve discussed India’s and Russia’s gold mania. Now it’s China’s turn. Today (Feb. 18), trading volumes for the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) benchmark cash contract hit an all-time high. Not that that’s exactly surprising—as global gold prices slid 3.4% on the global spot market last week, Chinese traders were blissfully sipping rice wine in their hometowns while on Lunar New Year holiday. They returned today to a buying opportunity.

The surge prompted Market Watch to ask if China will “ride to gold’s rescue.” Though the SGE is the world’s biggest exchange for physical gold, the Chinese government tightly controls it by, among other things, managing import and export licenses (and China is the world’s biggest producer). So its influence on global gold prices isn’t always direct.

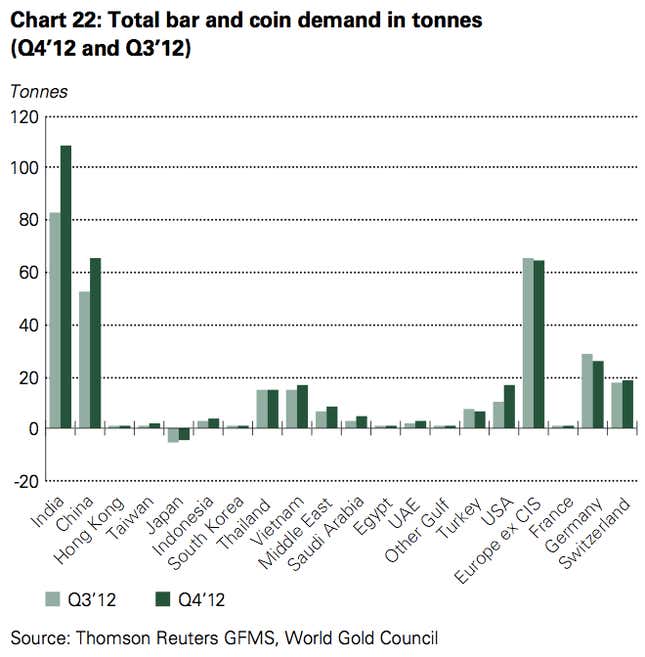

Still, Chinese consumers are a key force of consumer demand for gold, accounting around a quarter of the global total, according data just released by the World Gold Council (pdf, p.23). That amounted to $43.3 million and 805 tonnes (887 tons). Meanwhile, the China Gold Association says China consumed 33% more gold by weight (link in Chinese) in 2012 than it did in 2011. Here’s a look at the latest quarter:

While gold is popular in China as jewelry, it also functions as an alternative asset to the Chinese yuan. Chinese capital controls make it hard to change yuan for foreign currency and invest overseas. Even though the Chinese authorities have been slowly loosening currency exchange rules, the vast majority of Chinese people still have limited investment options. That’s one of the reasons that China sees so many bizarre asset bubbles (the bad art bubble and the pu’er tea bubble spring to mind).

Gold, therefore, is not just a hedge against inflation, though it’s certainly that as well (paywall). It also offers a crucial form of diversification. That may be one reason why the Chinese government is gearing up to release gold ETFs in China this year.

But that move is also tied to the government’s aim of opening up its gold market to foreign investors, which is one element of liberalizing capital controls. For instance, by allowing yuan-denominated gold contracts to trade in Hong Kong in 2011, the government is letting investors buy and sell gold contracts as a way of trading yuan.

Then there’s the mystery of China’s central bank’s gold-purchasing. Gold watchers have in the past attributed discrepancies between the amount of gold traded and that imported from Hong Kong to buying by the People’s Bank of China. However, the central bank no longer publicizes its investments, making it impossible to verify.

Those factors don’t necessarily mean that Chinese demand will keep gold above the psychologically important $1,600 an ounce, below which it fell last week for the first time in six months. But the Chinese government is promoting gradual steps toward yuan liberalization, including expanding the way gold can be traded. And the effect of those steps will take a while. Which suggests Chinese people’s need for that alternative isn’t going away any time soon.