Stem cells are biology’s magic elves. They have the power to differentiate into hundreds of types of cells. In an embryo, this process is central to making a fully-formed human. Later, it is crucial for maintaining and repairing the body.

In some cases, however, stem cells don’t do their jobs. About 5-10% of men are fully infertile, such that they cannot even use in-vitro fertilization techniques. One cause for their infertility is that their embryonic stem cells failed to go through a series of steps that result in healthy sperm-producing testes.

But there may be a way out for such men. In a world first, researchers at Nanjing Medical University in China report in Cell Stem Cell that they have created mouse sperm from stem cells in a lab and used them to produce fertile offspring. This raises hopes for treating male infertility through the creation of sperm from, say, skin cells.

The milestone study is the first to achieve the “gold standard” set a few years ago by stem-cell researchers. To do that, Chinese researchers had to go from stem cells to sperm-like cells through a series of pre-decided steps. At each step, the cells were supposed to have all the crucial parts—the right number of chromosomes, effective representation of the original donor’s DNA, etc. The final step involved using the sperm-like cells to produce healthy offspring.

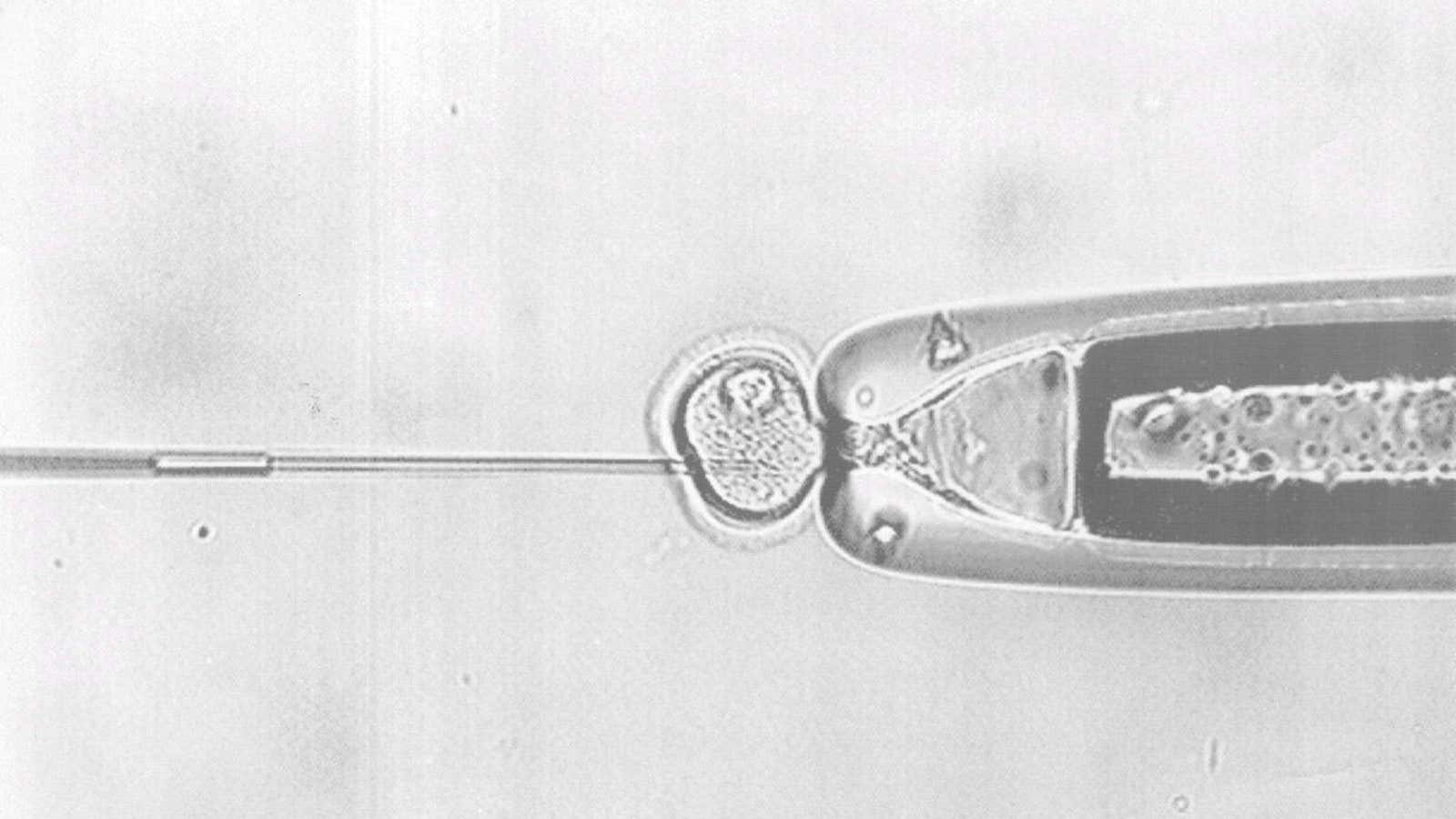

Here’s how it worked: Researchers exposed stem cells from mice embryos to a cocktail of chemicals that triggered their differentiation into germ cells, which could then become sperm or eggs. Once the differentiation began, they placed them next to natural tissue that mimicked testes and exposed the cells to testosterone. That enabled the stem cells to go through a series of steps and form spermatids—immature versions of sperm that have not yet grown tails. These spermatids were then injected in a mouse egg to create an embryo, which was then transferred to females who bore pups. These pups then went on to make a second generation of healthy pups through normal reproduction.

Researchers will have now to replicate these results in more mice, and eventually in humans. There is hope. Past research has shown that skin cells can be converted into pluripotent stem cells, which are equivalent to embryonic stem cells. These pluripotent stem cells have even been converted into precursors of sperm and egg cells.

Still, even if scientists succeed, they will need to show that the process is safe and ethical. What is the guarantee that lab-grown sperm will be the same as those that fully functioning testes would have created? Because of such concerns, fertility clinics in the UK, which is a world leader in the field, don’t permit the use of artificial sperm or eggs.

Even if the technique succeeds, it will take decades before male infertility ends. Still, at least, there is light at the end of the tunnel for men who have been unable to have children.