The neuroscience of “cool”

In the early 2000s, a major shift happened in the way people dress. Flared and baggy jeans began to give way to a skinny, low-slung version, and by the end of the decade, it seemed everyone—including men—were squeezing into jeans so tight that doctors began issuing health warnings. Now skinny is the status quo, and fashion’s early adopters are searching for a new look.

In the early 2000s, a major shift happened in the way people dress. Flared and baggy jeans began to give way to a skinny, low-slung version, and by the end of the decade, it seemed everyone—including men—were squeezing into jeans so tight that doctors began issuing health warnings. Now skinny is the status quo, and fashion’s early adopters are searching for a new look.

These sorts of back-and-forth trends may seem frustratingly arbitrary, but there’s a tremendous force involved in the shrinking and growing of jeans. It’s called ”cool.” It’s an incredibly powerful marketing tool—one that has driven the astronomical profits of companies from Nike to Apple to Kanye West’s Yeezy—and nowhere is its influence as obvious as in our clothes. Cool doesn’t just explain why people will pay $1,000 for the right sweatshirt. It’s also arguably a factor in why the right logo makes us view some people as more suitable for a job, or worthy of receiving money for charity.

What it is, exactly, is a little hard to define, but there are hints in its history, in trends, even in neuroscience. Cool is a target that’s constantly shifting. It’s an attitude, a term of approval, and today, as much as any of these things, it’s a game of superficially rebellious status-chasing, centered on consumerism.

You can actually see cool in the brain

Elusive as cool is, the way we experience it stems from some very specific places.

Steven Quartz and Anette Asp, neuroscience researchers at the California Institute of Technology, have run fMRI studies on the brains of people looking at items that a separate group identified as “cool” or “uncool.” Just viewing these objects activated a part of the subjects’ brains called the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). It’s involved in social emotions, such as pride and embarrassment, that center on how we perceive ourselves and believe others perceive us, and it has strong ties to the brain’s reward and disgust circuits.

The finding establishes an interesting connection between what we perceive as cool and our feelings about our place in society, as Quartz and Asp explain in their book, Cool: How the Brain’s Hidden Quest for Cool Drives Our Economy and Shapes Our World. The cooler the subject found the product to be—Quartz and Asp surveyed what they considered cool as well—the more active the MPFC became. They believe it suggests that the subjects’ brains were responding to how they thought the product might boost their esteem in the eyes of others.

“Cool turns out to be a strange kind of economic value that our brains see in products that enhance our social image,” they write. It’s a powerful quality: “This abstract good—social approval, reputation, esteem, or status—plays a central role in our motivation and behavior, and it is the currency that drives much of our economy and our consumption.”

Cool isn’t alone in raising status or getting people to buy. An item’s price tag can do that, too. But it’s distinct in one specific regard: It’s got a connotation of bucking the mainstream, and that’s where jeans come into play.

Cool is about breaking rules (or looking like you do)

There’s no better example of the power of cool than the rise of jeans, which are probably the world’s most popular garment.

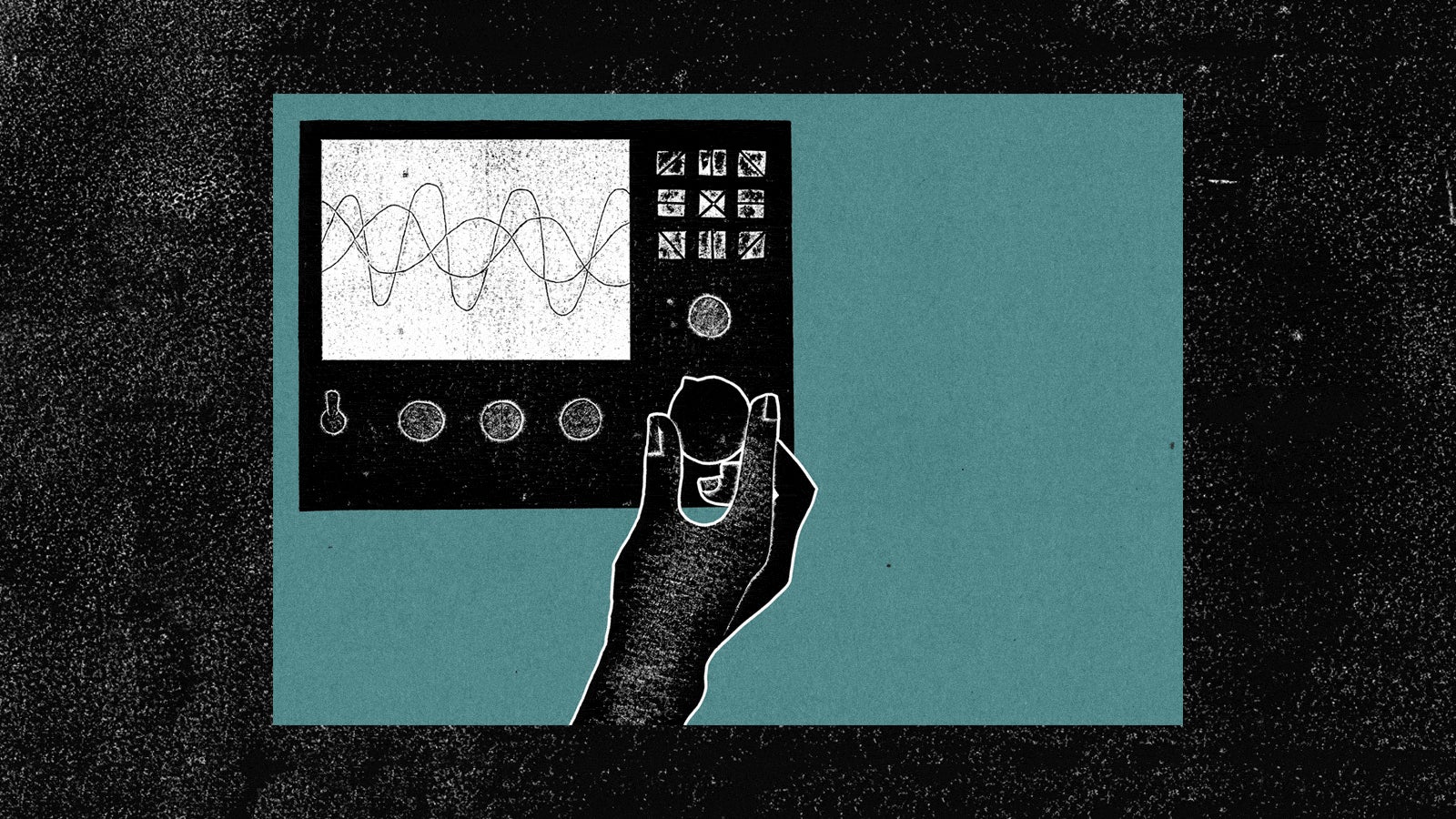

When Levi Strauss & Co. patented a design (pdf) in 1873 for denim work pants with riveted pockets for durability, it was creating a product for miners and cowboys. Those ”waist overalls,” which marked the birth of modern blue jeans, slowly gained popularity as casual clothes in the decades that followed. But they really took off in 1953, when a young Marlon Brando appeared in The Wild One.

Brando played a member of the kind of biker gangs that had been stirring up unrest across the US, wearing jeans and leather jackets. The character’s bad attitude, and the clothes representing it, stirred kids to a frenzy.

“The denim-clad rebel generated cultural excitement that bordered on hysteria,” Emma McClendon, a curator for the museum at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, writes in her book, Denim: Fashion’s Frontier.

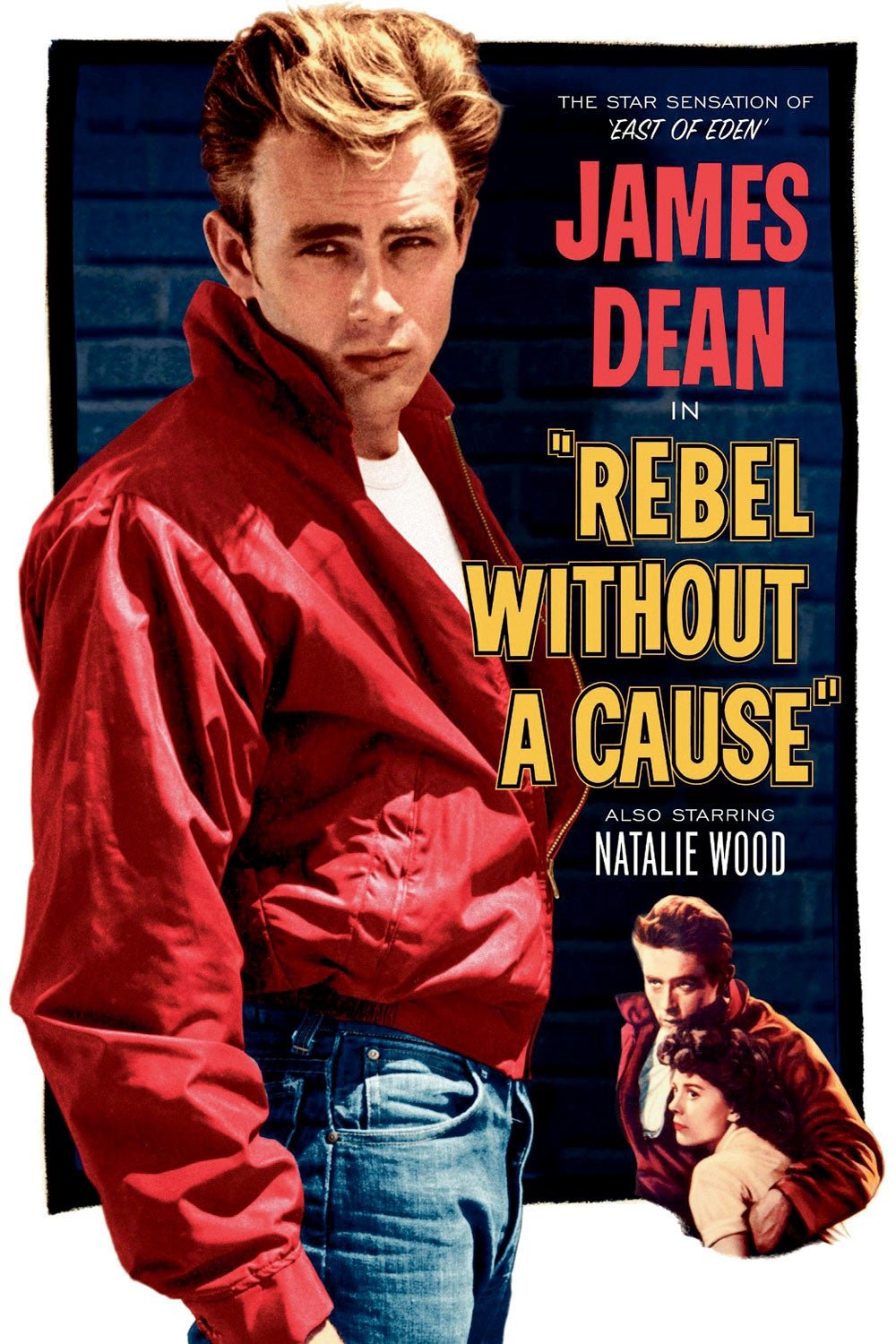

Because of The Wild One and later films, particularly Rebel Without a Cause starring James Dean, jeans became so linked to teenage rebellion that they were banned at a number of schools. By 1958, newspaper article noted that “about 90% of American youths wear jeans everywhere except ‘in bed and in church’ and that this is true in most sections of the country,” according to Levi’s (pdf).

As jeans grew in popularity, so did a word to describe their allure: cool. It had been around for centuries as a metaphor for maintaining composure—a “cool hand,” for instance. But it was black Americans at the turn of the 20th century who first used it as an expression of approval.

The word became part of the vocabulary of urban jazz culture, an outsider group in the racially segregated US. It maintained those shades of meaning as the mainstream absorbed it as shorthand for the detached iconoclasm of Brando and Dean.

Today, the same fetishizing of rebellion still plays out in “cool,” though in subtler ways, such as the popularity of items such as hooded sweatshirts. And in jeans. “Skinny jeans are such a convenient shorthand for youth and rebellion,” Rod Stanley, former editor of Dazed & Confused magazine, told the Guardian in 2013.

Cool is something you can buy

A pair of jeans isn’t exactly an all-out revolt against society. But it’s telling that a consumer product made for the working class took on such symbolic weight in 1950s America.

Wealth has long been a driver of status, but as the US postwar economy boomed, a large swath of society became more affluent. Money ceased to distinguish people as clearly as it once had.

Fashion at the time, and for much of history, was largely based on social class. Sociologist Georg Simmel, in a 1957 piece (pdf) in the American Journal of Sociology, described it as a process in which the “upper stratum of society” adopted a trend, was promptly imitated by the lower class, and then immediately abandoned it before it became common.

But Asp and Quartz argue that these new socioeconomic conditions in postwar American created an opening for a new kind of status competition. As the influence of social class decreased, people used cool as novel way to distinguish themselves and where they stood in society. Recent research lends the view some support.

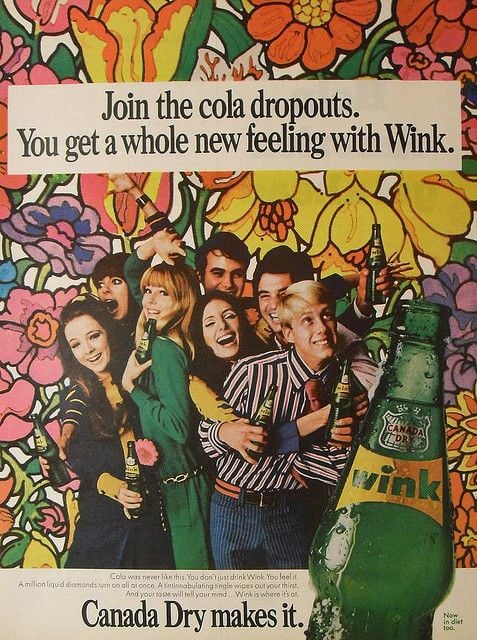

By the 1960s advertisers were using cool and its subtext of defiance as a tool to sell the growing counterculture everything from soda to menswear. It worked extraordinarily well, and continues to. ”Until we look cool to an American kid, we aren’t going to sell any gear to them,” Adidas’s head of North America said last year.

Much like class-based fashion before it, which Simmel called a type of “social adaptation,” it’s largely focused on adopting and abandoning trends. ”Coolness as a counterculture force may no longer reflect an actually rebellious value system, but rather a kind of rebellious-looking conformity to current social forces, particularly consumerism,” wrote a group of psychologists in a 2012 paper. Interestingly, other studies find it’s often associated with brands rather than particular styles.

To know what’s cool, follow the influencers

Cool is still a social phenomenon, though, and products have no power unless people give it to them. There exist whole companies dedicated to identifying influencers who set the tone for what’s cool, such as Barracuda NY, founded by Liz Fried. Unlike the “coolhunters” in Malcolm Gladwell’s well-known article for the New Yorker in 1997, Fried isn’t looking for trends. Clients including Ray-Ban and Salvatore Ferragamo have hired Fried to find people who she says are ”doing something unique, first, and well.”

“I had to infiltrate women’s exercise classes to find out whether front-row girls were influencers or not,” she says. (They weren’t.)

Brands may enlist them as consultants on certain projects, or pay them to represent their products, though how effective they actually are is open to debate. They could be relative unknowns who can sway a small niche, such as some of those Fried finds, or they may have a sizable following.

In fashion, one example is Gosha Rubchinskiy, the Russian designer and photographer who has led a trend of post-Soviet nostalgia and has collaborated with Reebok and Vans. Or Luka Sabbat, the 18-year-old “fashion influencer” and model profiled in the New York Times in April. “You want to know him. You want to be around him,” the managing director of one digital agency told the Times. “He’s the cool kid at the party we all want to be.”

Platforms such as Instagram have made it so that a much wider array of people than ever before can have influence. Recently, Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri noted that influencers on social media had helped sales by spurring acceptance of the brand’s new creative direction. Danielle Bernstein, the fashion blogger behind WeWoreWhat, earns up to $15,000 for a single sponsored Instagram post, because her 1.4 million followers look to her for inspiration in their own styles.

The image-sharing network has become a main venue for people and brands alike to signal their cool. You can even map their influence based on where they stand in the sprawling network of connections on the platform. Its constant barrage of imagery is even thought to be speeding up trend cycles by rapidly surfacing and overexposing new ideas. Influencers have become more valuable as a result, as their followers look to them to stay on top of what’s cool.

If what’s cool has become common, it’s time for a change

Even if a brand has figured out cool, it can quickly lose it if its products become overexposed. Status is relative. If everyone has the same thing, it diminishes its power, which is why exclusivity is so important. It’s a typical Veblen good, just with cool substituted for cost.

In denim, skinny jeans are now the status quo, and while they still rule in sales, people are starting to look to other styles. On the women’s runways, wide-leg jeans overtook their skinny counterpart for the first time in years at the spring-summer 2016 shows.

Currently there’s no brand that better embodies cool’s contradictions than Vetements, the Paris-based label that in just two years has become the biggest thing in fashion. It has been called “radical,“ yet its oversized hoodies and t-shirts riffing on the logo of shipping company DHL have become status symbols. Some think its popularity is killing its cool.

Fittingly, one of Vetements’ first big hits was a pair of straight-legged jeans, patched together from vintage Levi’s, that cost $1,450.

Still, what the next big trend in jeans will be isn’t yet clear. Nothing has jumped out to completely subvert the status quo. But maybe it won’t be jeans at all. It could be sweatpants.